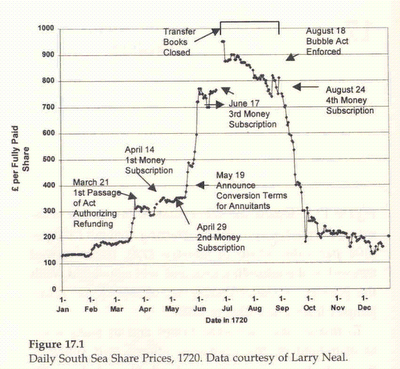

The fall in the price of bitcoin continues, to a new 2018 low. More evidence of the volatility of this commodity, which further undermines its potential as a virtual currency. After all, the whole point of a currency is to have some relatively stable view on its value. Yelland’s “This is a highly speculative asset”, looks right.

Other major cryptocurrencies – including Ripple XRP, Ethereum and Bitcoin Cash – are also falling. Many of them are seeing more dramatic swings even than bitcoin.

Other major cryptocurrencies – including Ripple XRP, Ethereum and Bitcoin Cash – are also falling. Many of them are seeing more dramatic swings even than bitcoin.

A few factors are playing here. Facebook has banned cryptocurrency advertising on its platform.

There have been several bitcoin exchange hacks, including the now famous US$534m job on Coincheck.

And South Korea, one of the main trading centres, has banned anonymous trades, effective 30th January 2018. Also the country’s customs service says that around 637.5bn KRW (US$598.6m) worth of foreign exchange crimes have been uncovered. That said, South Korea is not planning to ban cryptocurrency trading, the country’s finance minister has said.

After China shut down the largest cryptocurrency exchanges last September, and also banned Initial Coin Offerings, Japan has taken on the mantle of bitcoin’s new capital, where strong interest in currency trading AND technology align. In fact Japan had 51% of global trading volumes in January 2018. Bitcoin is also recognised as a payment mechanism there, and regulators there have introduced measures to monitor transactions on the lookout for criminal activity.

Today Japan’s financial regulator on Friday swooped on Coincheck Inc with surprise checks of its systems and said it had asked the Tokyo-based cryptocurrency exchange to fix flaws in its computer networks well before hackers stole $530 million of digital money last week, one of the world’s biggest cyber heists.

German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier on Thursday warned the financial sector that it had a responsibility to prevent speculation and the formation of trading bubbles in the cryptocurrency market. Steinmeier told about 1,000 guests at a Deka Bank event in Frankfurt that a new debate was needed about regulating cryptocurrencies, given recent gyrations in their valuations.

Ajeet Khurana, the head of the India’s blockchain and cryptocurrency committee, told the YourStory website, the government, like all governments in the world apart from Japan, did not recognise cryptocurrency as money. Many websites have been reporting, falsely, that Indian Finance Minister Arun Jaitley told parliament while presenting the national budget that India would make cryptocurrencies illegal.

Locally, Assistant Treasurer Michael Sukkar, speaking at a financial services briefing on Wednesday night, confirmed the Turnbull government is investigating how it could tax digital currencies like bitcoin.

In the U.S., Bank of America is now the largest lender barring customers from using credit cards to buy cryptocurrencies. According to Bloomberg, the policy was made known to employees yesterday and took effect today. Neither Discover nor Capital One allow crypto transactions on their cards. JPMorgan still does.

Expect more volatility ahead.