He says the Bundesbank actively shapes the ongoing conversation about distributed ledger technology (DLT) by contributing insights of its own, not least because as a central bank, trust is its most precious asset. The stability and efficiency of systems alone is their primary concern.

They wish to neither hype up a “hot topic” nor hinder the development of highly promising innovations. But, healthy scepticism, coupled with curiosity and critical analysis, is warranted when it comes to both DLT and central bank-issued digital currency. He concludes that a Central bank-issued digital currency, is currently an unrealistic prospect.

“The road to a digital central bank – assuming there would be any benefits in the first place – would be a very lengthy one. At present, there is not even a recognised basic blockchain. Major consortiums are developing different types of basic blockchains, each with their own particular features. Not all of them can be used in the financial sector”.

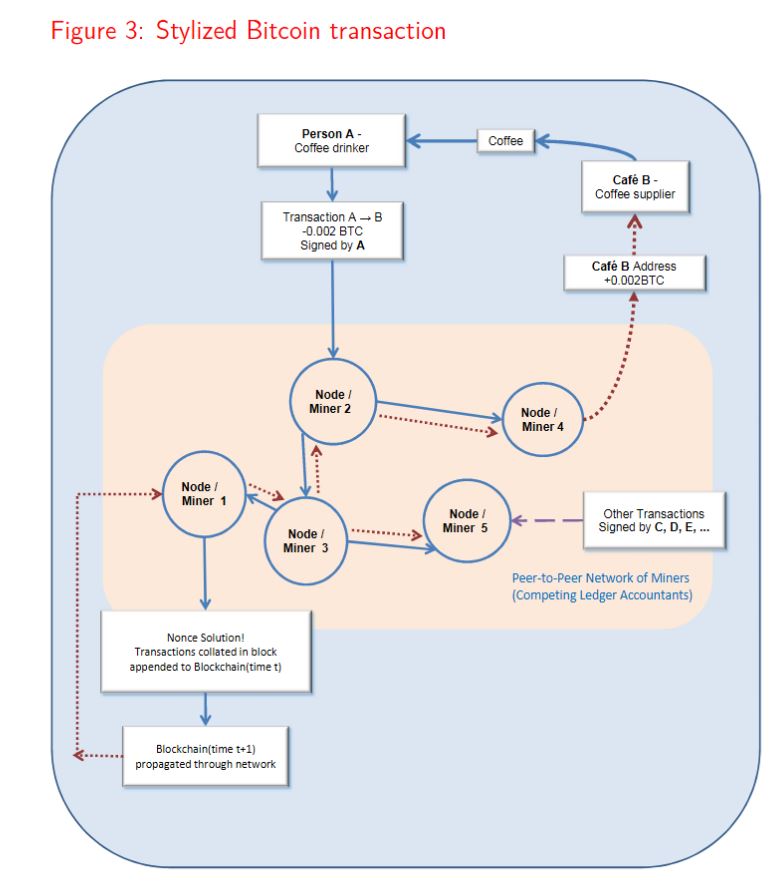

The original promise of Bitcoin was to forge a “trustless” payment system – that is, one that required no trust. I quote from Satoshi Nakamoto’s paper from 2008 (Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System): “What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party.”

I feel that too little attention is being paid to Nakamoto’s primary goal of constructing a groundbreaking, trustless electronic payment system which, like cash, would facilitate peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions. At the same time, Nakamoto was looking to create a currency which was not based on trust. This aspect – forging a new currency that does away with central banks – has become a major talking point in the current debate. I have come here today to explain why a trustless currency is not feasible, and I will also argue that the merits of blockchain can be harnessed more readily with trustworthy institutions than without.

To get a grasp of Bitcoin, we need to put our minds to the essence of money. There are two types of money. Money as a commodity, and money as a claim.

Money as a commodity, that could be a commonly used consumer good which is mostly non-perishable. Cigarettes, for instance, were used as a money substitute in Germany after the Second World War.

But equally, money could be a durable good – gold being the most prominent example of this. Gold is extraordinarily durable, and it has an intrinsic value as a sought after industrial metal, say, or as jewellery. Indeed, for centuries, delivering gold was regarded as the ultimate form of settling a claim.

Consumer and durable goods which can be used as money substitutes both have an intrinsic, consumption or utility value.

Virtual currencies, meanwhile, which are transferred much like goods, are a fabrication. That is not to consign them straight to the category of “fraud”. Yet they have no intrinsic value, just an exchange value. You can’t consume or use them, only exchange them.

On the other hand, there is money as a claim. The bulk of our money – central bank money and commercial bank money – is a claim on either the central bank or a commercial bank.

Every euro in cash and every euro in credit balances in TARGET2 represents a liability for the Eurosystem. And the euro is backed by the Eurosystem with its constituent central banks, one of which is the Bundesbank.

Unlike consumer or durable goods, central bank money does not have any consumption or utility value. And the issuing central bank’s credit quality and integrity is reflected in the value of its currency. The value of a currency, then, hinges on trust in the central bank.

Not just that: the issuer – so in the euro’s case, the Eurosystem – takes collateral from its monetary policy counterparties as a “deposit” for providing euro currency. That indirectly anchors the euro in the real economy.

Virtual currencies, by contrast, have no issuer, no footing in the real economy. No one has to redeem them. They are a fabrication and propagate according to a fictitious set-up in virtual systems which, in some cases, can be altered or newly created at the whim of a small group of participants. What is more, their governance regime is opaque, if not to say obscure – not to mention the fact that the identity of the participant or participants – no one knows for sure how many there are – behind the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto remains shrouded in mystery.

Virtual currencies are exchanged in the same way as goods, but they have no intrinsic value of their own. That is undoubtedly one reason why their value is highly volatile. Over the long term, that naturally also exposes Bitcoin holders to the risk of total loss. For us, Bitcoin is not money, it is a speculative plaything. The great number of sometimes dubious initial coin offerings is a clear indication that Bitcoin is more of a funding instrument.

To repeat: it is more of a speculative plaything than a form of payment. Hence my repeated warnings against investing in virtual currencies. We are witnessing a remarkable increase in the value of some virtual currencies. But that does not alter the risk of total loss.

2 Blockchain/DLT in the world of payments

For us, Bitcoin’s most important contribution is the underlying blockchain technology, or to put it more broadly, distributed ledger technology (DLT). This technology could help boost efficiency in payment and settlement processes.

That is why we have been looking at this technology from three different perspectives. First, the Bundesbank develops and runs major payment and settlement systems, often in conjunction with other central banks, and in this context we explore innovative technical capabilities which can contribute to their stability and efficiency.

Second, the Bundesbank acts as a catalyst to forge improvements in payment operations and settlement structures. The better the Bundesbank grasps the practical implications of technologies or processes, the more forcefully it will be able to present its arguments, which always aim to preserve the stability and enhance the efficiency of payment and settlement systems.

Third, the Bundesbank monitors the stability of systems and tools used in the field of payments and settlement. Being able to gauge the relative merits of state-of-the-art technology is a key skill in this regard. That is why the Bundesbank – much like other central banks worldwide – has been putting a great deal of thought into DLT, even though this technology is still very much in its infancy.

Potentially, distributed data storage means that DLT can simplify reconciliation processes associated with complex work-sharing value added chains. DLT is seen as having disruptive potential since it generally allows transactions to be carried out directly – that is, without intermediaries.

Developed originally for the virtual currency Bitcoin, DLT will nonetheless require extensive modifications if it is to be adapted to the needs of the financial sector. For one thing, the legal framework as it stands requires participants to be identifiable, transactions to be kept secret from third parties, and transactions to be settled with finality.

For another, transaction throughput needs to be high. That said, some of the consensus mechanisms, as they are known, absorb so much time and energy that efficient settlement seems barely possible. Furthermore, they require substantial additional data transfers, which adds to the costs.

For comparison purposes, the Bitcoin network, at its peak, settles roughly 350,000 transactions worldwide every day, and given its current configuration, appears to be running at almost full capacity. The German payment system alone, meanwhile, processes more than 75 million transactions on average every business day, according to the data for 2016.

The traditional answer to the problem of mounting complexity in the interactions of a multitude of independent participants has been to use a central bank – an institution which centralises the settlement of payment transactions. Hence the name: Central. Bank. This arrangement channels the many different bilateral payment flows and order books into larger flows which are then routed via or by the central bank and posted in a central bank account. That was a huge step towards greater stability and efficiency in the world of payments.

As a matter of fact, that is why we are seeing a trend towards centralisation and hierarchical structures in the development of basic blockchains as well. There are multiple reasons why a pure P2P settlement arrangement does not appear viable.

A pure P2P world appears unfeasible without trusted institutions. I call this factor the lack of a real reference framework. Bitcoins, you see, are merely virtual, and they change hands between virtual participants. They never leave the Bitcoin blockchain, and they will never have a real point of reference until they are exchanged for real currency, which takes place outside the blockchain.

Once real transactions come into play, a real point of reference is needed. You can trade a house on the blockchain in the form of a virtual token. But on the blockchain, that tells you nothing about whether the house even exists, whether it has the features it is said to possess, and whether it belongs to the seller in the first place. To verify all those things, there needs to be a trustworthy outside third party.

The basic matter of a participant’s personal identity needs to be verifiable outside the blockchain. Only then can we conduct real transactions with that participant.

That is why I feel that the purported goal of settling transactions without trustworthy third parties is a pie in the sky proposition.

All in all, we are highly sceptical about the extent to which DLT can be put to use in the financial sector. Given the current state of the art, it is somewhat unlikely that DLT will become a widely used application in individual and retail payments.

In the field of securities settlement, though, the shrinking processing times and reconciliation costs might prove to be a more important factor and suggest that DLT does have its uses.

The Deutsche Bundesbank is analysing the pros and cons of DLT in a project it is running with Deutsche Börse. While this project indicates that DLT does indeed have its functional merits, it is still unclear how far DLT also has the edge over today’s technology in terms of security, efficiency, costs and speed.

3 Central bank-issued digital currency

When using DLT, the question might arise in future as to whether central bank-issued digital currency could be provided for the safe settlement of larger transactions.

Central bank-issued digital currency would rank alongside cash and credit balances with the central bank as another form of central bank money, and it would also need to be posted as a liability on the central bank’s balance sheet.

There are several technical options in terms of the form this would take. Transfers could be value-based (like cash) or account-based (like deposits), anonymous or registered, its use could be restricted – in terms of amount or payment purpose, say – and it could be remunerated or, like cash, earn no interest.

The specific design dictates not just how far the supposed benefits of DLT-based central bank-issued digital currency will come into play, but also the macroeconomic repercussions, which also need to be factored into any overall verdict on its merits.

Arguably, the most important question here concerns who exactly should be allowed to use central bank-issued digital currency, or, to be more specific, whether central bank-issued digital currency should be issued to non-banks as well. Because if that were the case, we would probably see substitution effects between the different forms of money. Confining its use to the settlement of transactions among banks, on the other hand, would not involve any substantial changes over the status quo.

In particular, non-banks could convert their sight deposits at banks into central bank-issued digital currency if storage as an entry on the distributed ledger appears more secure and more convenient than hoarding it as cash.

Significant parts of non-banks’ sight deposits being shifted into a blockchain, however, and no longer being available to the credit institutions as virtually unremunerated funding might have considerable repercussions for the interest margin, the scale of lending as well as the business models in the banking system and the banking system’s structure.

Moreover, simply expanding the monetary base accompanied by sight deposits being shifted into central bank-issued digital currency would require a larger amount of collateral and would thus have a significant impact on the structure and risk profile of the central banks’ balance sheets.

There is a wide variety of potential monetary policy and stability policy implications. And these are currently being investigated by a number of central banks. As things stand, the likely consequences remain to be seen.

In a nutshell, the title of my speech today: “From Bitcoin to digital central bank money – still a long way to go” sums up the status quo of our considerations.

The road to a digital central bank – assuming there would be any benefits in the first place – would be a very lengthy one. At present, there is not even a recognised basic blockchain. Major consortiums are developing different types of basic blockchains, each with their own particular features. Not all of them can be used in the financial sector.

At the same time, applications for payment and settlement systems are being developed on these shifting sands. There is a lot going on in this field. Technology has been advancing at a pace unseen in the past decades.