We need measures of residential property price inflation. They need to identify bubbles, the factors that drive them, instruments that contain them, and analyse their relation to recessions. Such measures are also needed for the System of National Accounts and may be needed as part of the measurement of owner-occupied housing in a consumer price index. So, timely, comparable, proper measurement is a prerequisite for all of this, driven by concomitant data.

The problem of quality-mix adjustment

Critical to price index measurement is the need to compare, in successive periods, transaction prices of like-with-like representative goods and services. Price index measurement for consumer, producer, and export and import price indexes (CPI, PPI and XMPIs) largely rely on the matched-models method. The detailed specification of one or more representative brand is selected as a high-volume seller in an outlet, for example a single 330 ml. can of regular Coca Cola, and its price recorded. The outlet is then revisited in subsequent months and the price of the self-same item recorded and a geometric average of its price and those of similar such specifications in other outlets form the building blocks of a price index such as the CPI. There may be problems of temporarily missing prices, quality change, say size of can or sold as a bundled part of an offer if bought in bulk, but essentially the price of like is compared with like every month. RPPIs are much harder to measure.

First, there are no transaction prices every month/quarter on the same property. RPPIs have to be compiled from infrequent transactions on heterogeneous properties. A higher (lower) proportion of more expensive houses sold in one quarter should not manifest itself as a measured price increase (decrease). There is a need in measurement to control for changes in the quality of houses sold, a non-trivial task.

The main methods of quality adjustment are (i) hedonic regressions; (ii) use of repeat sales data only; (iii) mix-adjustment by weighting detailed relatively homogeneous strata; and (iv) the sales price appraisal ratio (SPAR). The method selected depends on the database used. There needs to be details of salient price-determining characteristics for hedonic regressions, a relatively large sample of transactions for repeat sales, and good quality appraisal information for SPAR. In the US, for example, price comparisons of repeat sales are mainly used, akin to the like-with-like comparisons of the matched models method, Shiller (1991). There may be bias from not taking full account of depreciation and refurbishment between sales and selectivity bias in only using repeat sales and excluding new home purchases and homes purchased only once. However, the use of repeat sales does not require data on quality characteristics and controls for some immeasurable characteristics that are difficult to effectively include in hedonic regressions, such as a desirable or otherwise view from the property.

The problem of source data

Second, the data sources are generally secondary sources that are not tailor-made by the national statistical offices (NSIs), but collected by third parties, including the land registry/notaries, lenders, realtors (estate agents), and builders. The adequacy of these sources to a large extent depends on a country’s institutional and financial arrangements for purchasing a house and varies between countries in terms of timeliness, coverage (type, vintage, and geographical), price (asking, completion, transaction), method of quality-mix adjustment (repeat sales, hedonic regression, SPAR, square meter) and reliability; pros and cons will vary within and between countries. In the short-medium run users may be dependent on series that have grown up to publicize institutions, such as lenders and realtors, as well as to inform users. Metadata from private organizations may be far from satisfactory.

We stress that our concern here is with measuring RPPIs for FSIs and macroeconomic analysis where the transaction price, that includes structures and land, is of interest. However, for the purpose of national accounts and analysis based thereon, such as productivity, there is a need to both separate the price changes of land from structures and undertake adjustments to price changes due to any quality change on the structures, including depreciation. This is far more complex since separate data on land and structures is not available when a transaction of a property takes place. Diewert, de Haan, and Hendriks (2011) and Diewert and Shimizu (2013a) tackle this difficult problem.

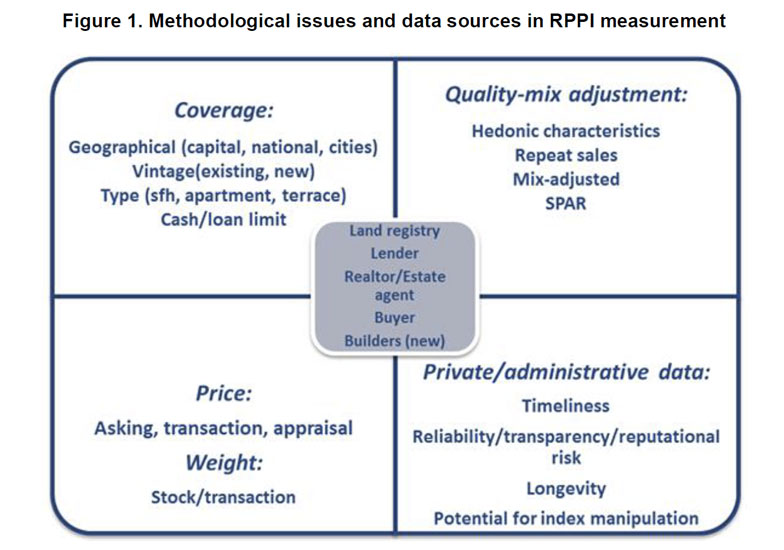

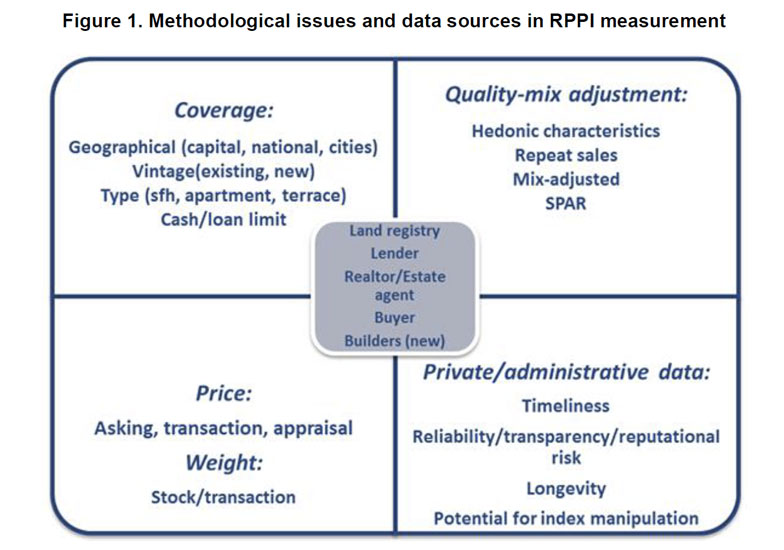

Figure 1 shows alternative data sources in its center and coverage, methods for adjusting for quality mix, nature of the price, and reliability in the four quadrants. Land registry data, for example, may have an excellent coverage of transaction prices, but have relatively few quality characteristics for an effective use of hedonic regressions, not be timely, and have a poor reputation. Lender data may have a biased coverage to certain regions, types of loans, exclude cash sales, have “completion” (of loan) price that may differ from transaction price, but have data on characteristics for hedonic quality adjustment. Realtor data may have good coverage, aside from new houses, data on characteristics for hedonic quality adjustment, but use asking prices rather than transaction prices.

The importance of distinguishing between asking and transaction prices will vary between countries as the length of time between asking and transaction varies with the institutional arrangements for buying and selling a house and the economic cycle of a country.

Whether measurement matters

A natural question is whether the differences in source data and methodologies used matters to the overall outcome of the index. Silver (2015) undertook an extensive formal analysis based on the RPPIs and, as explanatory variables, the associated methodological and source data for 157 RPPIs from 2005:Q1 to 2010:Q1 from 24 countries. The resulting panel data had fixed-time and fixed-country effects; the estimated coefficients on the explanatory measurement variables were first held fixed and then relaxed to be time varying. Subsequently, the explanatory variables were interacted with the country dummies.

The rest of the paper examines, consolidates, and provides improved practical methods for the timely estimation of hedonic RPPIs, though, as noted earlier, the proposed methods apply equally to CPPIs. Hedonic regressions are the main mechanism recommended for and used by countries for a crucial aspect of RPPI estimation—preventing changes in the quality-mix of properties transacted translating to price changes.

The rest of the paper examines, consolidates, and provides improved practical methods for the timely estimation of hedonic RPPIs, though, as noted earlier, the proposed methods apply equally to CPPIs. Hedonic regressions are the main mechanism recommended for and used by countries for a crucial aspect of RPPI estimation—preventing changes in the quality-mix of properties transacted translating to price changes.

RPPIs and CPPIs are hard to measure. Houses, never mind commercial properties, are infrequently traded and heterogeneous. Average house prices may increase over time, but this may in part be due to a change in the quality-mix of the houses transacted; for example, more 4-bedroom houses in a better (more expensive) post-code transacted in the current period compared with the previous or some distant reference period would bias upwards a measure of change in average prices. A purpose and crucial challenge of RPPIs and CPPIs is to prevent changes in the quality-mix of properties transacted translating to measured price changes. The need is to measure constant-quality property price changes and while there are alternative approaches, the concern of this paper is with the hedonic approach as a recommended widely used methodology for this.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.