If there is one simple lesson from the crisis that we all can embrace, it is that no financial institution in America should be so big or complex that its failure would put the financial system at risk. Congress wrote that simple lesson into law as a core principle of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act).

Consequently, a fundamental change in our framework of regulation as a result of the crisis is to impose tougher rules on banking organizations that are so big or complex that their risk taking and distress could pose risks to financial stability. Whereas previously, our regulatory framework took a homogeneous approach focused narrowly on the safety and soundness of an institution, the reforms underway take a tailored approach to also address the risks posed by an institution to the safety and soundness of the system.

Five years on, it is an opportune time to ask how far along we are in accomplishing that basic imperative. I would argue we are at a pivotal moment when many of the key requirements that apply differentially to the biggest and most complex institutions will be finalized and their impact will become clear.

In the immediate wake of the crisis, the central focus was to reduce leverage and build capital across the banking system while also addressing risks in derivatives and short-term wholesale funding markets. For instance, considerable effort went into the new Basel III capital framework, whose key elements apply across the entire banking system. With these important foundations laid, attention turned to the tougher standards for institutions whose size and complexity are such that their distress could pose risks to the system as a whole.

Tailoring Standards for Greater Systemic Risk

The Dodd-Frank Act requires the Board to adopt enhanced prudential standards for large banking organizations, as well as for nonbank financial companies that have been designated as systemically important, and to tailor the standards so that their stringency increases in proportion to the systemic footprint of the institutions to which they apply. In addition, rigorous planning and operational readiness for recovery and resolution are required to ensure that big, complex institutions are subject to the same market discipline of failure as other normal companies in America.

Within this framework, the first line of defense is to require big, complex institutions to maintain a very substantial stack of common equity in order to enhance loss absorbency and to induce the institutions to internalize the associated risks to the system. These requirements are designed to lower their probability of “material financial distress or failure” in order “to prevent or mitigate risks to the financial stability of the United States.

The proposed capital surcharge is the regulatory requirement that is most clearly calibrated to the size and complexity of an institution. Last December, the Board proposed a framework of risk-based capital surcharges for the eight U.S. banking organizations identified as global systemically important banks by the Financial Stability Board. The capital surcharges under the proposal are estimated to range from 1.0 percent to 4.5 percent of risk-weighted assets based on 2013 data. The capital surcharge would be required over and above the 7 percent minimum and capital conservation buffer required for all banking organizations under Basel III, and in addition to any countercyclical capital buffer.

The capital surcharge is designed to build additional resilience and lessen the chances of an institution’s failure in proportion to the risks posed by the institution to the financial system and broader economy. The surcharge is calibrated so that the expected costs to the system from the failure of a systemic banking institution are equal to the expected costs from the failure of a sizeable but not-systemic banking organization. In other words, if the failure of a systemic banking institution would have five times the system-wide costs as the failure of a sizeable but not-systemic banking organization, the systemic banking institution would be required to hold enough additional capital that the probability of its failure would be one-fifth as high. The capital surcharge should help ensure that the senior management and the boards of the largest, most complex institutions take into account the risks their activities pose to the system.

Importantly, the surcharge is calibrated in proportion to how an institution scores on specific metrics that capture the system-wide costs of its failure–risks associated with size, interconnectedness, complexity, cross-border activities, substitutability, and short-term wholesale funding. With respect to the last, the logic is that greater reliance on short-term wholesale funding increases the risks of creditor runs and asset fire sales that can both erode the institution’s capital and spark contagion. By calibrating the enhanced capital expectation in direct proportion to a set of measures of size, interconnectedness, and complexity, the proposal provides clear and measurable incentives for institutions to simplify and reduce their systemic footprint.

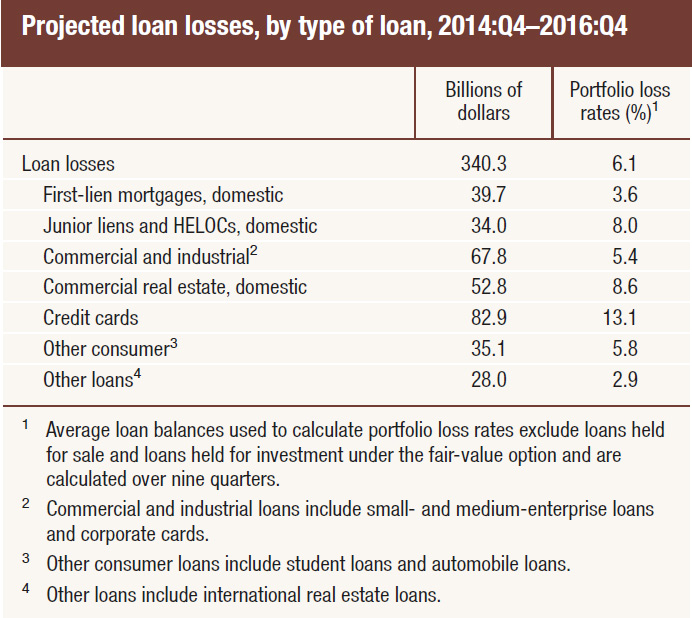

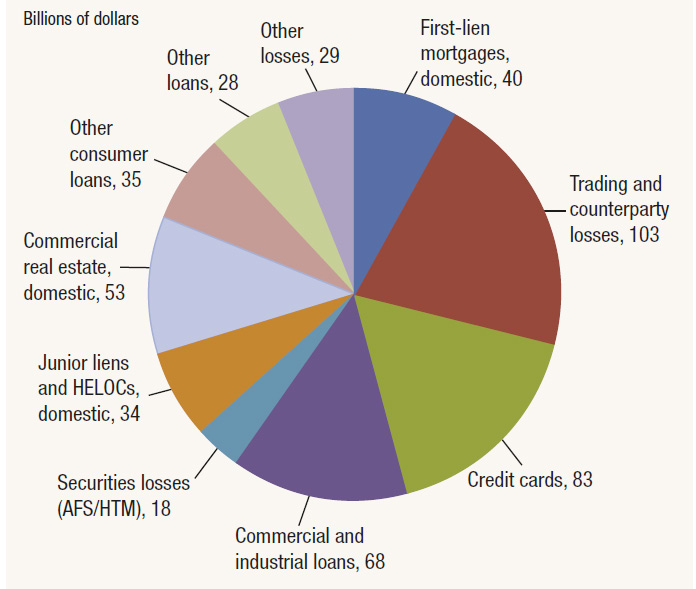

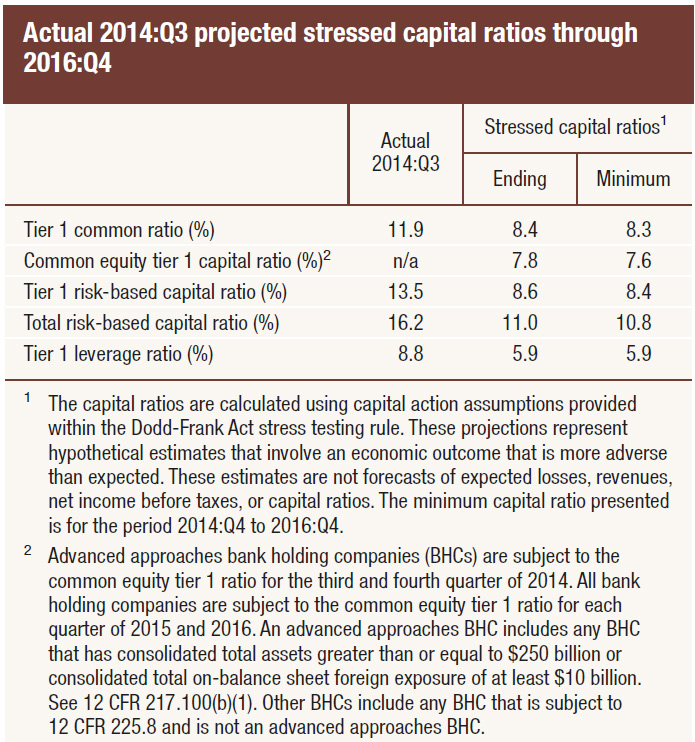

Second, the crisis also provided a stark reminder that what may seem like thick capital cushions in good times may prove dangerously thin at moments of stress, when losses soar and asset valuations plummet. Therefore, in addition to static capital requirements, large banking institutions must undergo the forward-looking Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) and supervisory stress test each year to assess whether the amount of capital they hold is sufficient to continue operations through periods of economic stress and market turbulence, and whether their capital planning framework is adequate to their risk profile.

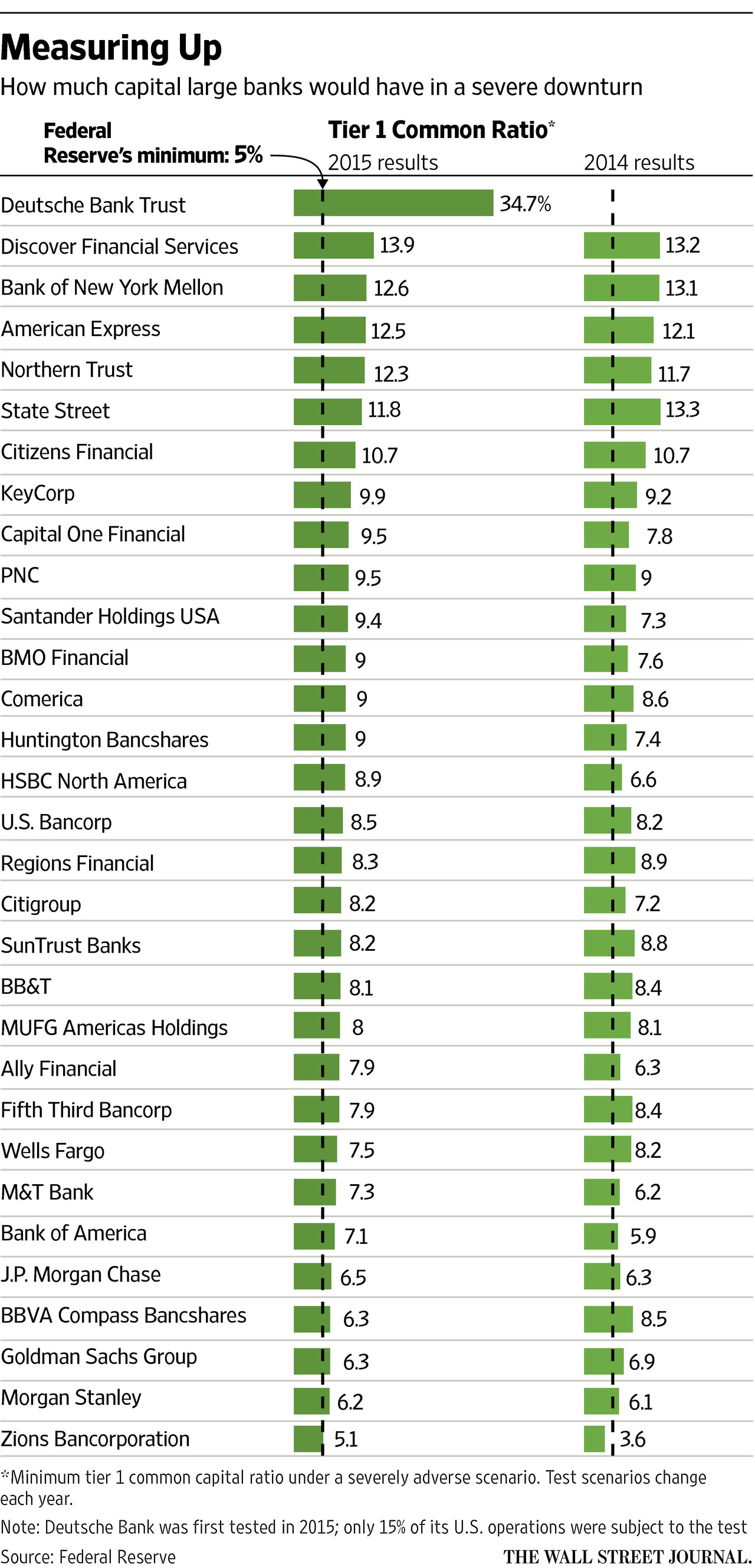

While supervisory stress tests with adverse and severely adverse macroeconomic scenarios are required by statute for all bank holding companies with assets over $50 billion, for the eight U.S. systemic banking institutions, the stress tests are tailored to include a counterparty default scenario, and, for the six systemic institutions with significant trading activities, the stress tests also include a global market shock. In significant part as a result of these additional requirements, in 2015, the eight systemic institutions needed to hold common equity worth 4.7 percent of risk-weighted assets on average above the 7 percent minimum and capital conservation buffer in order to meet the CCAR post-stress minimum requirement, given their planned capital distributions. That’s more than twice the average common equity increment above the regulatory capital minimum plus capital conservation buffer required of the next largest group of banks, those with $250 billion or more in assets that are not globally systemic.

In addition to the quantitative assessments, CCAR provides a powerful process for assessing the quality of each institution’s risk modeling and internal controls on a portfolio by portfolio basis. This is particularly important for institutions where the sheer size and complexity of their activities make it very challenging for even the highest-quality senior executives to effectively monitor and control risk.

The CCAR and stress test exercises provide valuable, forward-looking mechanisms to ensure that large banking institutions can meet their minimum capital ratios through the cycle. For the systemic banking institutions, it will be important to assess incorporating the risk-based capital surcharge in some form into the CCAR post-stress minimum in order to ensure these institutions remain sufficiently resilient to reduce the expected losses to the system through periods of financial and economic stress. Conceptually, the stress test and the capital surcharge should work to reinforce each other–not to substitute for each other.

Third, as we learned from the crisis, risk modeling and risk weighting are subject to considerable uncertainty, and stressed financial markets can make even the most rigorous risk assessments look optimistic in hindsight. Thus, the Basel III capital framework includes a simple, non-risk-adjusted ceiling on leverage that is designed not to bind under most circumstances while providing a robust cushion as a backstop. Although all internationally active U.S. banking organizations are subject to a 3 percent leverage standard that takes into account on- and off-balance sheet exposures under Basel III,6 our systemic banking institutions are required to meet a higher 5 percent leverage standard. The higher leverage standard for the systemic banking institutions is designed as a backstop to the surcharge-enhanced risk-based capital standard, reflecting the higher potential losses to the system from the failure of systemic institutions.

Fourth, in addition to the surcharge, regulatory minimum, and capital conservation buffer, starting in 2016 and phasing in through 2019, the U.S. banking agencies could require the largest, most complex U.S. banking firms to hold a countercyclical capital buffer of up to 2.5 percent of risk-weighted assets when it is warranted by rising macroprudential risks.

In sum, if the tailored capital framework that is under construction had been in place in 2007, the largest, most complex banking institutions could have been required to hold common equity of up to 14 percent of risk-weighted assets on average, which is roughly double the amount of common equity they held at the time.

Fifth, the crisis shined a harsh light on the severe inadequacies in the banking system not only in capital, but also with respect to liquidity risk management. At key moments of financial stress, run-like behavior in the short-term funding markets threatened the solvency of some large, complex banking organizations and compelled them to engage in asset fire sales. As part of the enhanced prudential standards mandated under the Dodd-Frank Act and Basel III liquidity reforms, large banking organizations are now required to maintain substantial buffers of high-quality liquid assets calibrated to their funding needs in stressed financial conditions. They are also required to maintain certain amounts of stable funding based on the liquidity characteristics of their assets.

As with assessments of capital, supervisors also evaluate liquidity at the largest firms in annual horizontal exercises called the Comprehensive Liquidity Analysis and Review (CLAR). In part because of these measures, the total amount of high-quality liquid assets held by the eight U.S. systemic banking institutions has increased by over 60 percent, or $1 trillion, since 2011 to $2.4 trillion currently. And whereas these institutions were materially more reliant on short-term wholesale funding than deposits before the crisis, now the reverse is the case.

Finally, the structure of incentive compensation also came under scrutiny post-crisis with the recognition that the heavy emphasis on stock options and bonuses created skewed incentives that provided substantial rewards for short-term risk taking going into the crisis. The logic of imposing tougher standards on large and complex institutions whose activities could pose risks to the broader financial system extends to requiring better alignment of the incentives of senior executives and senior risk managers with the longer-term fortunes of their banking institutions. Most simply, this calls for a greater share of compensation to be deferred for several years. Under the proposal issued by the Board and other federal financial regulatory agencies in 2011 to implement section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, at least 50 percent of incentive compensation of certain executive officers at financial institutions with total consolidated assets of $50 billion or more would have to be deferred over a period of at least three years, and the deferred amounts would need to be adjusted for actual losses that are realized during the deferral period.

Beyond this, for systemic banking institutions, I would like to see consideration given to changing the structure of deferred compensation so that it better balances the interests of the full set of the firm’s stakeholders over the longer term. In particular, when evaluating risky activities, senior executives should internalize not only the upside risk faced by stockholders, but also the downside risk borne by bondholders, especially as that better aligns with the public interest in reducing the likelihood of material financial distress or failure at the systemic banking institutions.9 This set of considerations should help to inform ongoing deliberations regarding implementation the Dodd-Frank Act incentive compensation provisions.

Making Failure Safe

You can see now why I argue we are reaching a key moment in our efforts to build a more resilient financial system. In combination, these more stringent standards, several of which are still in train, should prove powerful in inducing systemic banking institutions to reduce the risks they pose to the system. Beyond this, Congress sought to address too big to fail by requiring systemic institutions to plan and prepare for failure, and by creating a new “orderly liquidation authority.” Under section 165(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act, large bank holding companies are required to submit credible plans for their rapid and orderly resolution under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. In addition, the orderly liquidation authority created under title II of the Dodd-Frank Act empowers the U.S. government to put a failing systemic banking institution into a governmental resolution procedure as an alternative to resolution under the Bankruptcy Code.

The resolution planning process provides regulators with an important tool to address too big to fail. And we have set the bar realistically high, reflecting lessons from the crisis in the requirements that large banking institutions must meet to ensure their plans and preparations are not deemed to be deficient by the regulators.11

Earlier this month, the eight U.S. systemic banking institutions submitted their most recent resolution plans, which are currently under review. Each of the submissions must provide detailed work plans in several specific areas that have been found to be critical for orderly resolution.

First, an orderly resolution requires that the large, complex firms simplify and rationalize their structures to align their legal entities with business lines and reduce the web of interdependencies among them to ensure separability along business lines. As the crisis made clear, the tangled web of thousands of interconnected legal entities that were allowed to proliferate in the run up to the crisis stymied orderly wind down and contributed to uncertainty and contagion.

Second, the largest, most complex banking organizations must demonstrate operational capabilities for resolution preparedness. These capabilities include maintaining an ongoing, comprehensive understanding of the obligations and exposures associated with payment, clearing, and settlement activities across all the material legal entities and developing strong processes for managing, identifying, and valuing collateral across all the material legal entities. Capabilities for resolution preparedness also include establishing mechanisms to ensure that there would be adequate capital, liquidity, and funding available to each material legal entity under stressed market conditions to facilitate orderly resolution.

These steps, in turn, hinge on each institution demonstrating the requisite management information systems capabilities to ensure that key data related to each material legal entity’s financial condition, financial and operational interconnectedness, and third-party commitments is readily accessible on a real-time basis.

Fourth, the largest, most complex banking organizations are required to develop robust operational and legal frameworks to ensure continuity in the provision of shared or outsourced services to maintain critical operations during the resolution process.

Fifth, the largest, most complex banking organizations are in the process of amending financial contracts to provide for a stay of early termination rights of external counterparties, recognizing that the triggering of cross-default provisions proved to be a major accelerant of contagion at the height of the crisis and greatly impeded cross border cooperation.

Sixth, the largest, most complex banking organizations are required to develop a clean top-tier holding company structure, in which the parent’s obligations are not supported by guarantees provided by operating subsidiaries, to support resolvability. This will be critical for any institution pursuing the single point of entry strategy.

In addition, the publicly disclosed summary of each institution’s plan is required to include information on the strategy for resolving each material legal entity and what an institution would look like following resolution in order to bolster public and market confidence that resolution would be orderly.

We look forward to assessing the plans submitted earlier this month, which we expect to demonstrate concrete progress on the detailed feedback that was provided by the regulators over the past year. In parallel, Board supervision staff have been engaged in an extensive horizontal review of the operational readiness of the systemic banking institutions on several dimensions of the resolution planning that were detailed in earlier supervisory guidance. Together, the annual plan submissions along with the ongoing supervisory examination of operational readiness provide potent, complementary mechanisms in addressing too big to fail.

Finally, in order to make the firms resolvable, it will be necessary for the largest, most complex firms to maintain enough long-term debt at the top-tier holding company that could be converted into equity to recapitalize the institution’s critical operating subsidiaries so as to prevent contagion. The availability of sufficient capacity at the parent to both absorb losses and recapitalize the critical operating subsidiaries is designed to provide comfort to other creditors of the firm and thereby forestall destructive runs, since the long-term unsecured debt issued by the parent holding company would be structurally subordinate to the claims on the operating subsidiaries. We are in the process of developing a proposal for a long-term debt requirement that would fully address the estimated capital needs of each institution in a gone-concern scenario.

Scale and Scope

Having provided a detailed assessment of the measures Congress chose to require in order to address too big to fail, it is worth spending a minute reflecting on what Congress chose not to require in the Dodd-Frank Act. In particular, it is noteworthy that Congress did not prescribe major changes to scope or scale of systemic institutions in the too-big-to-fail toolkit.

One rationale is that the public sector on its own is unlikely to be the best judge of the optimal scope and scale of financial institutions. While the private sector may be in a better position to judge the market benefits associated with economies of scope and scale and business models associated with particular banking organizations, the public sector is likely to be a better judge of the risks that their size, interconnectedness, and complexity pose to the financial system. Accordingly, the Dodd-Frank Act assigns regulators the responsibility for calibrating requirements such that investors, senior executives, and board members internalize those risks.

Notwithstanding the fact that the law does not prescribe broad structural changes, some observers may judge whether reform has gone far enough based on the extent of changes in the scope or scale of the U.S. systemic banking institutions relative to the crisis. These eight banking institutions now hold $10.6 trillion in total assets and account for 57 percent of total assets in the U.S. banking system today–not materially different from the $9.4 trillion and 60 percent of total assets in 2009. And while some of the U.S. systemic banking institutions have reduced their capital markets activity, they remain the largest dealers in those markets.

To be fair, we are entering an important period when the more stringent standards that we are putting in place to reduce expected losses to the system should inform the cost-benefit analysis of these institutions’ size and structure. As standards for systemically important firms tighten, some institutions may determine that it is in the best interest of their stakeholders to reduce their systemic footprint. Indeed, there already have been some notable structural changes at a few of the largest institutions over the past few years that are not readily apparent from looking at the aggregate assets across the systemic institutions. But it is also possible that some may judge that the economies of scale and scope are such that it makes sense to maintain their systemic footprint, even at the expense of the greater regulatory burdens necessary to protect the system relative to those faced by their non-systemic competitors.

One thing we can all agree is that we have a more resilient and dynamic financial system as a result of having a very large number of banking organizations, in different size classes, pursuing different business models. Indeed, that diversity is one of the hallmarks of the U.S. system, which distinguishes it from many other advanced economies. Accordingly, we want to make sure that our regulatory framework supports banks in the middle of the size spectrum, as well as community banks, and the customers they serve. Thus, by the same rationale that argues for the greater stringency of the standards associated with greater systemic risk at the top end of the scale and complexity spectrum, we will carefully examine opportunities to ease burdens at the lower end of the spectrum. And we will want to continue to refine our regulatory standards, using the authorities under Dodd-Frank to make sure they are tailored to be commensurate with the risk to the system.