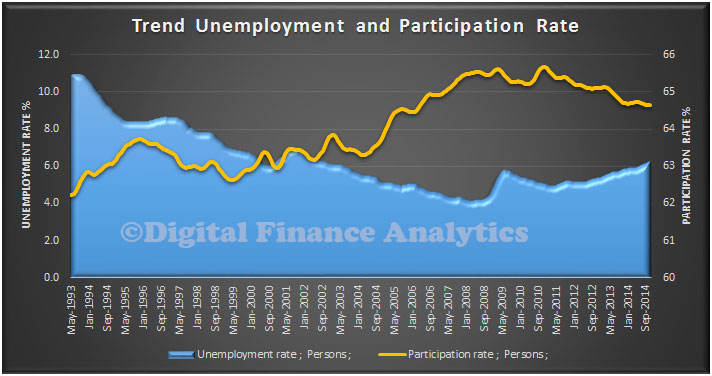

Against expectations, in trend terms, the unemployment rate was unchanged at 6.0 per cent in June, as announced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) today. The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for June 2015 was 6.0 per cent, an increase of 0.1 percentage points from a revised 5.9 per cent for May 2015.

The seasonally adjusted labour force participation rate increased less than 0.1 percentage points to 64.8 per cent in June 2015.

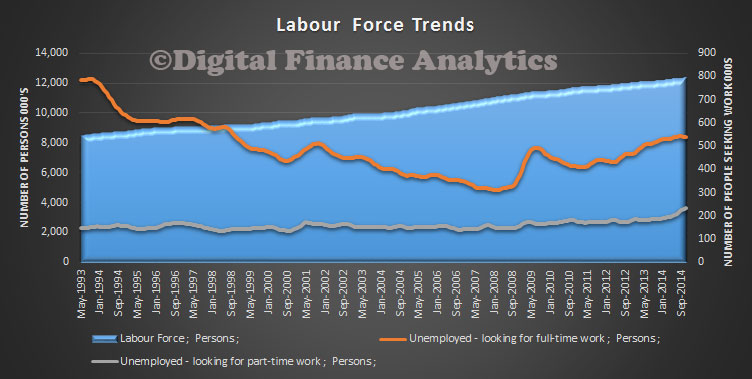

The ABS reported the number of people employed increased by 7,300 to 11,768,600 in June 2015 (seasonally adjusted). The increase in employment was driven by increases in full-time employment for both females (up 17,500) and males (up 7,000). The increase in full-time employment was partially offset by decreases in part-time employment for both females (down 10,600) and males (down 6,600).

The ABS seasonally adjusted aggregate monthly hours worked series increased in June 2015, up 5.1 million hours (0.3%) to 1,636.9 million hours.

The seasonally adjusted number of people unemployed increased by 12,800 to 756,100 in June 2015. This was driven by unemployed people who looked for full-time work, which increased by 27,200 to 541,200.

In contrast the Roy Morgan Research unemployment number for June was 9.3% down 1.3% from a year ago. This alternative method of assessing unemployment rates is consistently higher than the ABS rate. This Roy Morgan survey on Australia’s unemployment and ‘under-employed’ is based on weekly face-to-face interviews of 437,819 Australians aged 14 and over between January 2007 – June 2015 and includes 4,233 face-to-face interviews in June 2015.

Both sets of measures indicate that currently employment opportunities are keeping pace with demand, keeping the rate at a high, but not rising figure.