There is an assumption that as employment rates and growth picks up, the much needed wage growth will follow. We discussed this on ABC’s The Business last week, with HSBC’s Chief Economist who held the view that the RBA won’t lift the cash rate here until wages growth comes through. We were not so sure.

But an interesting piece from the The IMFBlog suggests there are more fundamental forces at work, especially in terms of employment patterns and the rise of part-time work, which suggests that unemployment and wage growth is more disconnected now. We think underemployment is one of the most critical drives of wage stagnation. If this is true, then wages may be lower for longer, which is not good news for those households with heavy debt burdens, especially if rates rise. We release our September analysis of mortgage stress next week. Here is the IMF commentary:

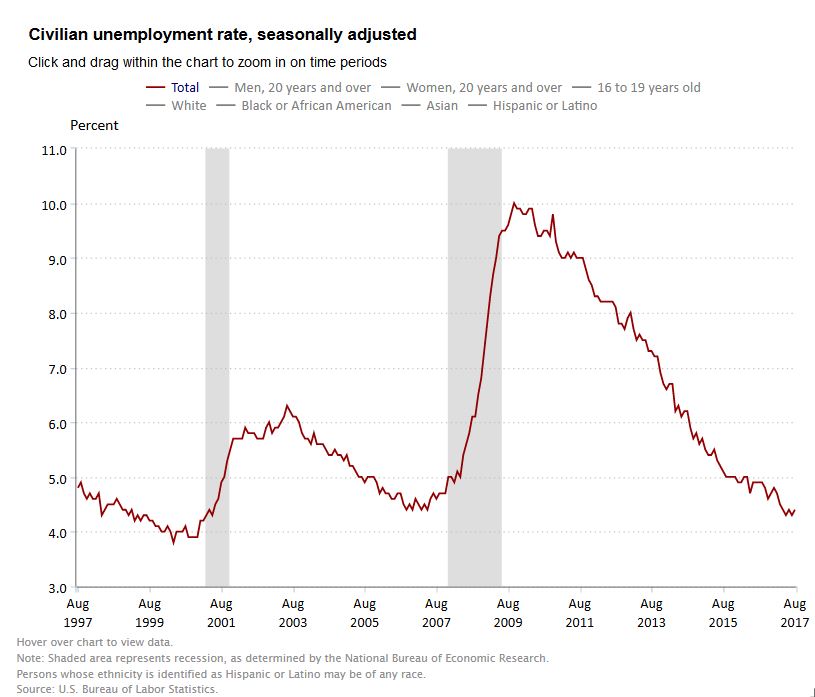

Over the past three years, labor markets in many advanced economies have shown increasing signs of healing from the Great Recession of 2008-09. Yet, despite falling unemployment rates, wage growth has been subdued–raising a vexing question: Why isn’t a higher demand for workers driving up pay?

Our research in the October 2017 World Economic Outlook sheds light on the sources of subdued nominal wage growth in advanced economies since the Great Recession. Understanding the drivers of the disconnect between unemployment and wages is important not only for macroeconomic policy, but also for prospects of reducing income inequality and enhancing workers’ security.

Job growth picked up, wage growth less so

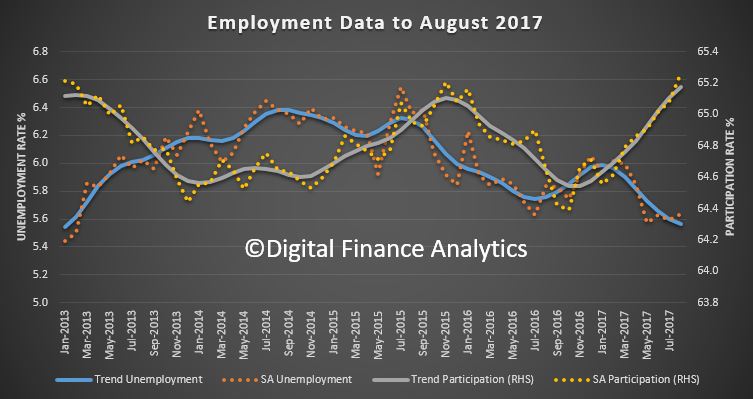

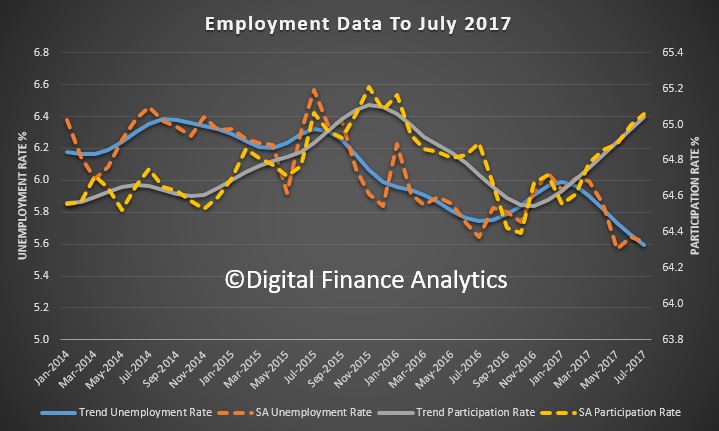

In many cases, employment growth has picked up and headline unemployment rates are now back to their pre-Great Recession ranges. Still, nominal wage growth remains well below where it was prior to the recession. Sluggish wages may reflect deliberate efforts to slow down wage growth from unsustainably high levels, as was the case with some countries in Europe. But the pattern is more widespread.

There are several factors at play in explaining this pattern, both cyclical and structural – or slow-moving – in nature.

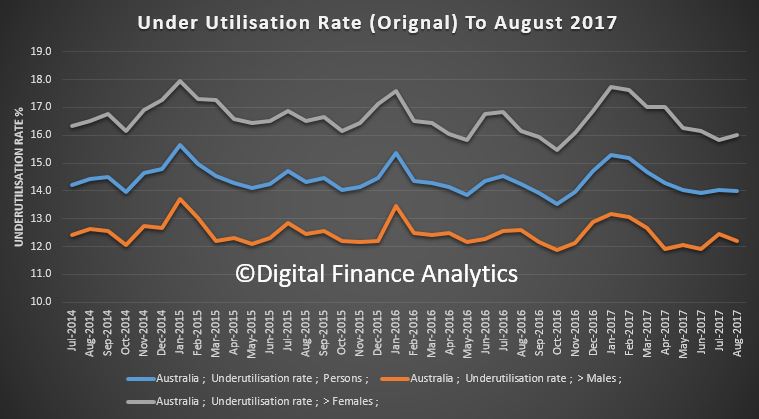

A key cyclical factor is labor market slack – that is, the excess supply of labor beyond the amount that firms would like to employ.

First off, however, it is important to recognize that headline unemployment rates may not be as indicative of labor market slack as they used to be. Hours per worker have continued to decline (extending a trend that began before the Great Recession).

Several countries have also experienced higher rates of involuntary part-time employment (workers employed for less than 30 hours per week who report they would like to work longer) and an increased share of temporary employment contracts These developments in part reflect continued weak demand for labor (itself a reflection of weak final demand for goods and services).

Another key driver of wage growth is the widely-recognized slowdown in trend productivity growth. Sustained weakness in output per hour worked can squeeze business profitability and eventually weigh on wage growth as firms becomes less willing to accommodate fast increases in compensation.

Slower-moving factors

Besides these forces, slower-moving factors such as ongoing automation (proxied by the falling relative price of investment goods) and diminished medium-term growth expectations also appear to hold back wage growth. However, our analysis suggests that automation may not have made a large contribution to subdued wage dynamics following the Great Recession.

The analysis also indicates sizable common global factors behind wage weakness in the aftermath of the Great Recession and especially during 2014–16. In other words, labor market conditions in other countries appear to have a growing effect on wage setting in any given economy. This points to the possible roles of the threat of plant relocation across borders, or an increase in the effective worldwide supply of labor in a context of closer international economic integration.

Putting it all together

The relative roles of labor market slack and productivity growth vary across countries. In economies where unemployment rates are still appreciably above their averages before the Great Recession (such as Italy, Portugal, and Spain), high unemployment can explain about half of the slowdown in nominal wage growth since 2007, with involuntary part-time employment acting as a further drag on wages. Wage growth is therefore unlikely to pick up until slack diminishes meaningfully—an outcome that requires continued accommodative policies to boost aggregate demand.

In economies where unemployment rates are below their averages before the Great Recession (such as Germany, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom), slow productivity growth can account for about two-thirds of the slowdown in nominal wage growth since 2007. Even here, however, involuntary part-time employment appears to be weighing on wage growth, suggesting greater slack in the labor market than headline unemployment rates capture. Assessing the true degree of slack in these economies will be important when determining the appropriate pace of exit from accommodative monetary policies.

Broader changes in the labor market

Our research further indicates that sluggish wage growth has occurred in a context of broader changes in the labor market. The increase in involuntary part-time employment itself, for example, is in part explained by cyclically-weak demand. Accommodative policies that help lift aggregate demand would therefore lower involuntary part-time employment. But it is also associated with slower-moving factors such as automation, diminished medium-term growth expectations, and the growing importance of the service sector.

Some of these developments represent persistent changes in relationships between firms and workers that mirror underlying shifts in the economy – with the emergence of the gig economy and shrinkage of traditional sectors such as manufacturing. Policymakers may therefore need to enhance efforts to address the vulnerabilities that part-time workers face. Examples of possible measures include broadening minimum wage coverage where it does not currently include part-time workers; securing parity with full-time workers by extending pro-rated annual, family, and sick leave; and strengthening secondary and tertiary education to upgrade skills over the longer term.