The EU have just published the latest stress testing on 51 banks from 15 EU and EEA countries covering around 70% of banking assets in each jurisdiction and across the EU. The results show significant variations across banks and countries and offers an unprecedented level of transparency across individual banks with over 16,000 data points per bank. RBA and APRA, please take note!

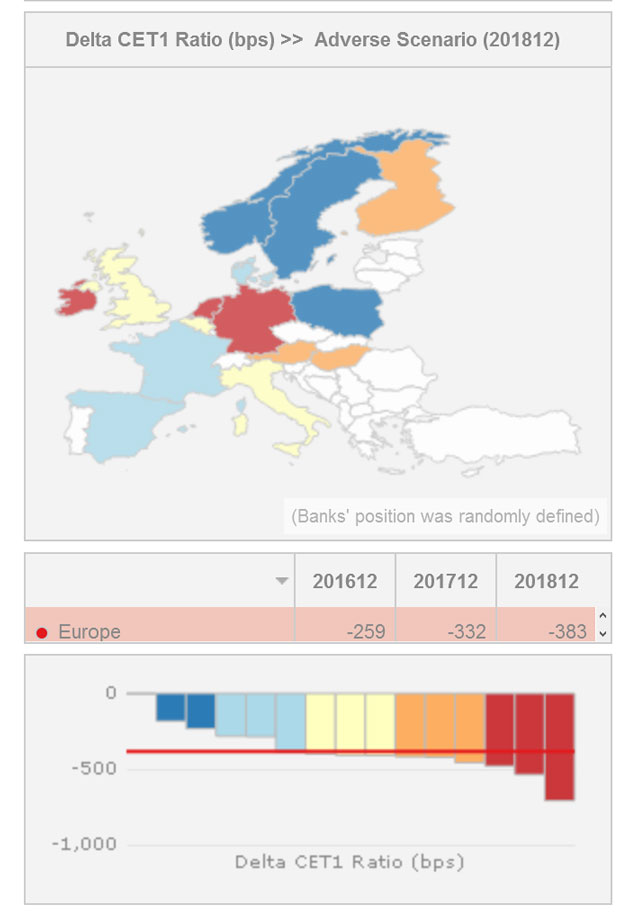

They have provided a powerful interactive tool to analyse the results. Here is a top level map by country, showing the relative change in CET1 ratios to 2018, in the adverse scenario.

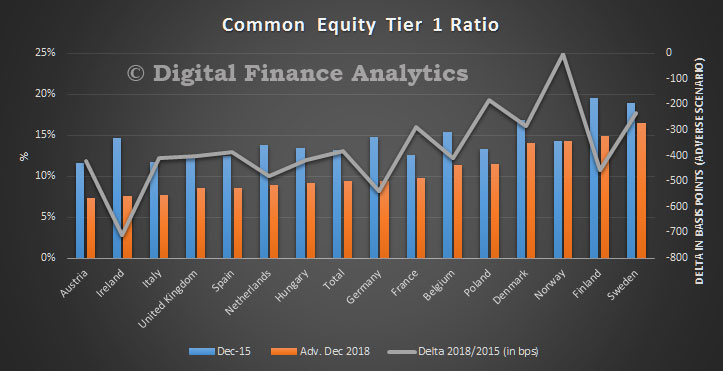

Banks in Austria, Ireland, Italy and the UK would have the lowest CET1 ratios in the adverse scenarios.

Banks in Austria, Ireland, Italy and the UK would have the lowest CET1 ratios in the adverse scenarios.

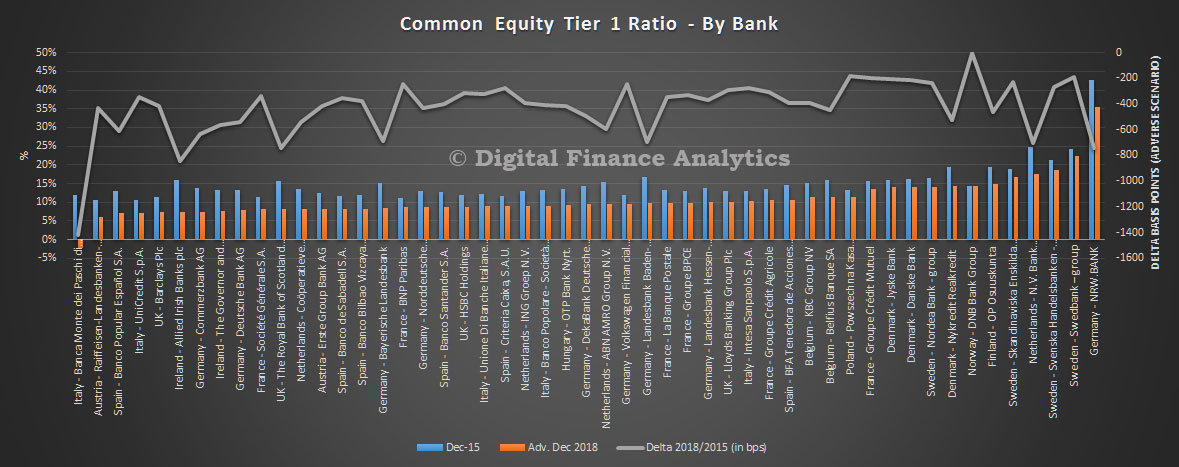

The data, bank by bank is also revealing, showing that there are significant variations.

The data, bank by bank is also revealing, showing that there are significant variations.

The EU‐wide stress test is primarily focused on the assessment of the impact of risk drivers on the solvency of banks. Banks are required to stress test the following common set of risks: Credit risk, including securitisations; Market risk, CCR and CVA; and Operational risk, including conduct risk.

The EU‐wide stress test is primarily focused on the assessment of the impact of risk drivers on the solvency of banks. Banks are required to stress test the following common set of risks: Credit risk, including securitisations; Market risk, CCR and CVA; and Operational risk, including conduct risk.

In addition to the risks listed above, banks are requested to project the effect of the scenarios on NII and to stress P&L and capital items not covered by other risk types.

The risks arising from sovereign exposures are covered in credit risk and in market risk, depending on their accounting treatment.

The adverse scenario implies EU real GDP growth rates over the three years of the exercise of ‐1.2%, ‐1.3% and 0.7% respectively – a deviation of 7.1% from its baseline level in 2018.

The 2016 EU-wide stress test does not contain a pass fail threshold. Instead it is designed to support ongoing supervisory efforts to maintain the process of repair of the EU banking sector.

The objective of the stress test is to provide supervisors, banks and other market participants with a common analytical framework to consistently compare and assess the resilience of large EU banks to adverse economic developments. Along with the results, the EBA is providing again substantial transparency of EU banks’ balance sheets, an essential step towards enhancing market discipline in the EU.

The EU banking sector has significant shored up its capital base in recent years leading to a starting point capital position for the stress test sample of 13.2 % CET1 ratio at the end 2015. This is 200 bps higher than the sample in 2014 and 400 bps higher than in 2011. The hypothetical scenario leads to a stressed impact of 380 bps on the CET1 capital ratio, bringing it across the sample to 9.4% at the end of 2018. The CET1 fully loaded ratio falls from 12.6% to 9.2%, while the aggregate leverage ratio decreases from 5.2% to 4.2% in the adverse scenario.

The impact is driven by:

- credit risk losses of €-349 bn contributing -370 bps to the impact on the CET1 capital ratio.

- operational risk (€-105 bn or -110 bps) of which conduct risk losses contributed -€71 bn or -80 bps to the CET1 impact

- market risk across all portfolios including CCR (€-98bn or -100bps).

The impact is partially offset by pre provision income flows, although these too are subject to stress factors and constraints in the methodology. For instance net interest income falls 20% in the adverse scenario from 2015 levels.

The impact ranges from close to 0 for the Norwegian bank in the sample to more than ‐700bps for banks from Ireland albeit with large differences within each country. The dispersion across all banks is thus not surprisingly larger with 14 banks projecting an impact of more than ‐500bps on a

transitional basis. One bank reports a reduction in the CET1 ratio of more than 14 percentage points. While for the majority of banks the impact on a transitional basis is approximately equal to or higher than the fully loaded impact, a few banks report a significantly, i.e. around 20%, higher fully loaded impact. For a small number of banks around half of the

transitional CET1 capital ratio impact is explained by transitional arrangements. Different phase‐in schedules across countries explain why for some countries the impact on a fully loaded and the impact on a transitional basis are identical while other countries show relatively large discrepancies. In this respect the largest differences are visible for banks from Germany and Spain.

Reflecting on the results, it is worth bearing in mind that many of the smaller banks (with 30% of bank assets), not caught in this set of tests are in a much worst state – including entities in Germany and Italy. Also, there is contention in some countries, (such as Italy, where banks probably need to have an injection of capital), between EU rules which stop governments providing more capital and risks to depositors and bond holders thanks to the EU preferred “bail-in” arrangements.