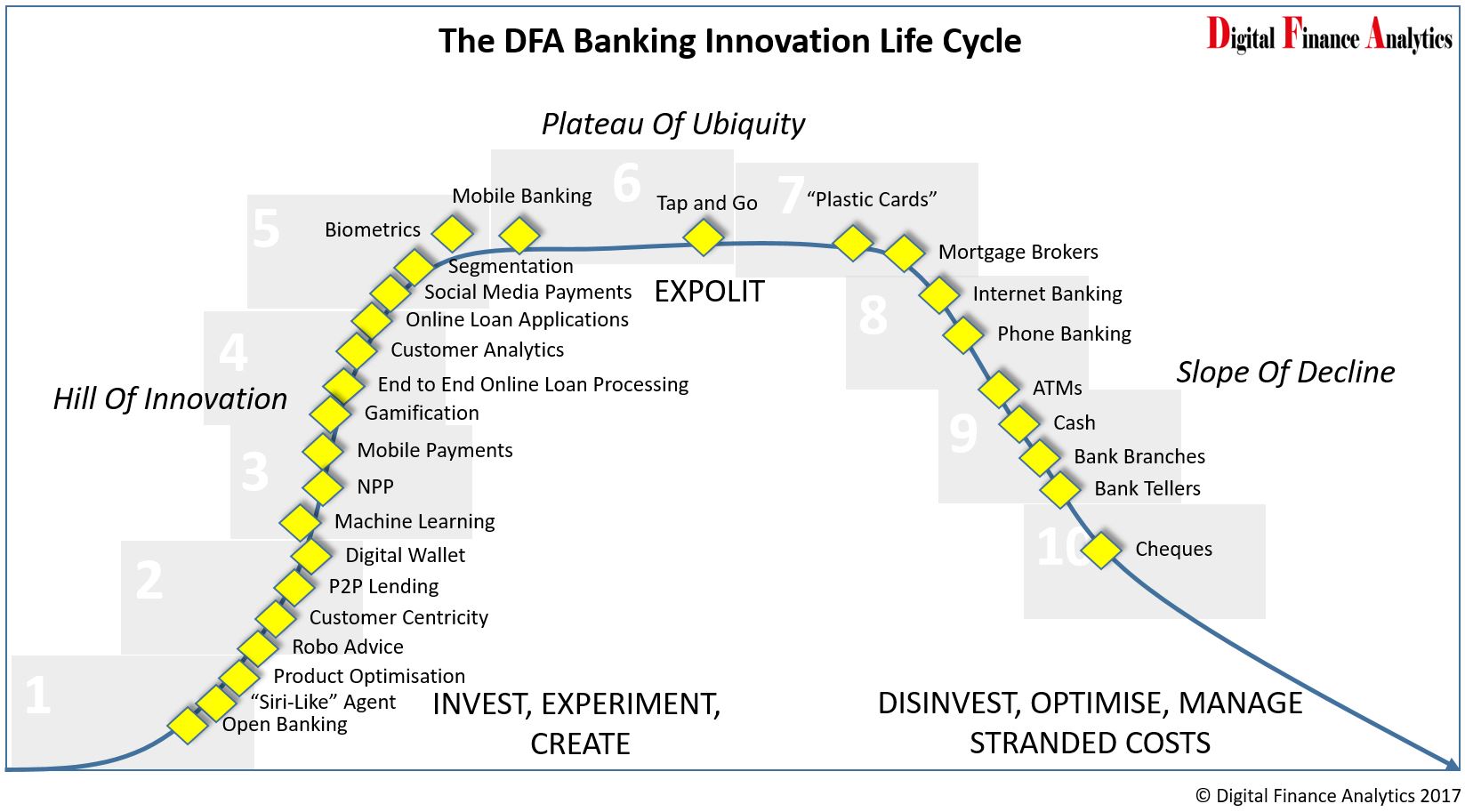

The new generation of fintech tools offers the potential to help consumers manage their increasingly complicated financial lives, but also poses risks that will need to be managed as the marketplace matures.

In many ways, the new generation of fintech tools can be seen as the financial equivalent of an autopilot. The powerful new fintech tools represent the convergence of numerous advances in research and technology–ranging from new insights into consumer decisionmaking to a revolution in available data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence (AI). They operate by guiding consumers through complex decisions by offering new ways of looking at a consumer’s overall financial picture or simplifying choices, for example with behavioral nudges.

As consumers start to rely on financial autopilots, however, it is important that they remain in the driver’s seat and have a good handle on what is happening under the hood. Consumers need to know and decide who they are contracting with, what data of theirs is being used by whom and for what purpose, how to revoke data access and delete stored data, and how to seek relief if things go wrong. In short, consumers should remain in control of the data they provide. In addition, consumers should receive clear disclosure of the factors that are reflected in the recommendations they receive. If these issues can be appropriately addressed, the new fintech capabilities have enormous potential to deliver analytically grounded financial services and simplified choices, tailored to the consumers’ needs and preferences, and accessible via their smartphones.

Consumers Face Complex Financial Choices

When the first major “credit card,” the Diner’s Club Card, was introduced in 1949, consumers could only use the cardboard card at restaurants and, importantly, only if they paid the entire amount due each month. Today, the average cardholder has about four credit cards, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimates that American consumers collectively carry $785 billion in credit card debt.

When signing up for a credit card, consumers face a bewildering array of choices. Half of consumers report that they select new cards based on reward programs, weighing “cash back” offers against “points” with their credit card provider that may convert into airline or hotel “miles,” which may have varying values depending on how they are redeemed. In some cases, rewards may apply to specific spending categories that rotate by quarter and require that consumers re-register each term, and the rewards may expire or be forfeited under complicated terms.

In some cases, the choices may be confusing. Let’s take the example of zero percent interest credit card promotions. A consumer may choose a zero percent interest credit card promotion and expect to pay no interest on balances during a promotional period, after which any balances are assessed at a higher rate of interest going forward. But if a consumer instead chooses a zero percent interest private-label credit card with deferred interest and has a positive balance when the promotional period expires, interest could be retroactively assessed for the full time they held a balance during the promotional period. Even sophisticated consumers could be excused for confusing these products.

As it turns out, it is often the most vulnerable consumers who have to navigate the most complicated products. For instance, one recent study of the credit card market found that the average length of agreements for products offered to subprime consumers was 70 percent longer than agreements for other products.

The complexity multiplies when we go beyond credit cards and consider other dimensions of consumers’ financial lives. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has found that nearly a quarter of the Americans that don’t maintain bank accounts are concerned that bank fees are too unpredictable. Even though mortgage debt is over two-thirds of household debt, nearly half of consumers don’t comparison shop before taking out a mortgage. Student loans now make up 11 percent of total household debt, more than twice its share in 2008. Over 11 percent of student debt is more than 90 days delinquent or in default–and researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimate that this figure may understate the problem by as much as half.

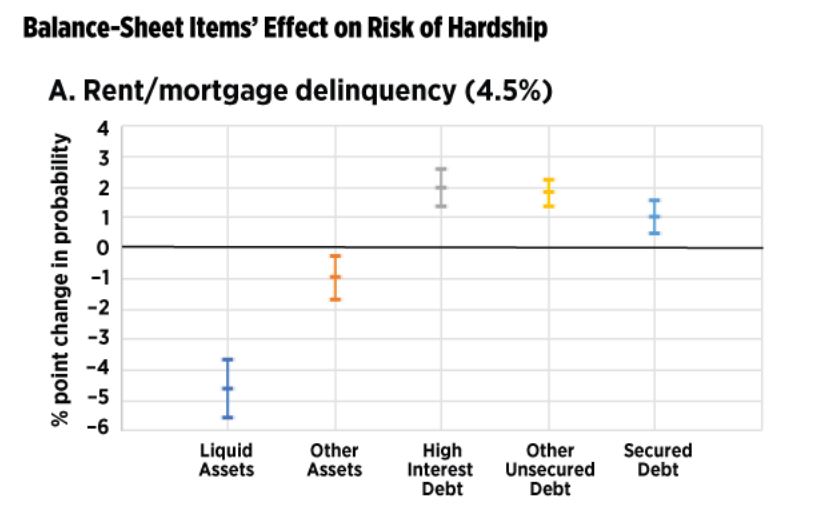

Today, consumers navigate numerous weighty financial responsibilities for themselves and their dependents. It seems fair to assume they could use some help managing this complexity. In the Federal Reserve Board’s annual Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED), more than half of respondents reported that their spending exceeded their income in the prior year. Indeed, 44 percent of SHED respondents reported that they could not cover an emergency expense costing $400 without selling something or borrowing money.

New Tools to Help Consumers Manage Their Finances

Given the complexity and importance of these decisions, it is encouraging to see the fast-growing development of advanced, technology-enabled tools to help consumers navigate the complex issues in their financial lives. These tools build on important advances in our understanding of consumer financial behavior and the applications, or “app,” ecosystem.

Researchers have invested decades of work exploring how consumers actually make decisions. We all tend to use shortcuts to simplify financial decisions, and it turns out many of these can prove faulty, particularly when dealing with complex problems. For example, empirical evidence consistently shows that consumers overvalue the present and undervalue the future. Researchers have documented that consumers make better savings decisions when they are presented with fewer options. They have shown the importance of “anchoring” bias–the tendency to place disproportionate weight on the first piece of information presented. This bias can lead consumers either to make poor financial choices or instead to tip the scales in favor of beneficial choices, as with automatic savings defaults. Similarly, “nudges” can help consumers in the right circumstances or instead backfire in surprising ways.

These behavioral insights are especially powerful when paired with the remarkable advances we have seen in the technological tools available to the average consumer, especially through their smartphones. Smartphones are ubiquitous. The 2016 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer and Mobile Financial Services (SCMF) found that 87 percent of the U.S. adult population had a mobile phone, the vast majority of which were smartphones. Smartphone use is prevalent even among the unbanked and underbanked populations. Survey evidence suggests we are three times more likely to reach for our phone than our significant other when we first wake up in the morning.

Some evidence suggests that smartphones are already helping consumers make better financial decisions. The 2016 SCMF found that 62 percent of mobile banking users checked their account balances on their phones before making a large purchase, and half of those that did so decided not to purchase an item as a result. In addition, 41 percent of smartphone owners checked product reviews or searched product information online while shopping in a retail store, and 79 percent of those respondents reported changing their purchase decision based on the information they accessed on their smartphone.

And those use cases just scratch the surface of what is possible. First of all, the smartphone platform has become a launch pad for a whole ecosystem of apps created by outside developers for a wide variety of services, including helping consumers manage their financial lives.

Second, the smartphone ecosystem puts the enormous computing power of the cloud at the fingertips of consumers. Interfacing with smartphone platforms and other apps, outside developers can tap the computing power of the leading cloud computing providers in building their apps. Importantly, cloud computing offers not only the power to process and store data, but also powerful algorithms to make sense of it. Due to early commitment to open-source principles, app developers have open access to many of the same machine-learning and artificial intelligence tools that power the world’s largest internet companies. Further, the major cloud computing providers have now taken these free building blocks and created different machine-learning and artificial intelligence stacks on their cloud platforms. A developer that wants to incorporate artificial intelligence into their financial management app can access off-the-shelf models of cloud computing providers, potentially getting to market faster than by taking the traditional route of finding training data and building out models in-house from scratch.

Third, fintech developers can also draw from enormous pools of data that were previously unavailable outside of banking institutions. Consumer financial data are increasingly available to developers via a new breed of business-to-business suppliers, called data aggregators. These companies enable outside developers to access consumer account and transactional information typically stored by banks. But aggregators do more than just provide access to raw data. They facilitate its use by developers, by cleaning the data, standardizing it across institutions, and offering their own application programming interfaces for easy integration. Further, similar to cloud computing providers, data aggregators are also beginning to provide off-the-shelf product stacks on their own platforms. This means that developers can quickly and easily incorporate product features, such as predicting creditworthiness, determining how much a consumer can save each month, or creating alerts for potential overdraft charges.

Researchers have documented the benefits of tailored one-on-one financial coaching. Until recently, though, it has been hard to deliver that kind of service affordably and at scale, due to differences in consumers’ circumstances. Let’s again consider the example of deferred interest credit cards. It turns out only a small minority of consumers miss the deadlines for repaying promotional balances and are charged retroactive interest payments, and they typically have deep subprime scores. Similarly, for consumers that opt into overdraft products on their checking accounts, 8 percent of consumers pay 75 percent of the fees. Up until now, it has been hard for consumers to understand those odds and objectively assess whether they are likely to be in the group of customers that will face challenges with a particular financial product. The convergence of smartphone ubiquity, cloud computing, data aggregation, and off-the-shelf AI products offer the potential to make tailored financial advice scalable. For instance, a fintech developer could pair historical data about how different types of consumers fare with a specific product, on the one hand, with a consumer’s particular financial profile, on the other hand, to make a prediction about how that consumer is likely to fare with the product.

The Evolution of Financial Autopilots

Since the early days of internet commerce, developers have tried to move beyond simple price comparison tools to offer tailored “agents” for consumers that can recommend products based on analyses of individual behavior and preferences. Today, a new generation of personal financial management tools seems poised to make that leap. When a consumer wishes to select a new financial product, he or she can now solicit options from a number of websites and mobile apps. These new comparison sites can walk the consumer through a wide array of financial products, offering to compare features like rewards, fees, and rates, or tailoring to a consumer’s stated goals. Some fintech advisors ask consumers to provide access to their bank accounts, retirement accounts, college savings accounts, and other investment platforms in order to enable a fintech advisor to offer a consumer a single, near complete picture of his balances and cash flows across different institutions.

In reviewing the advertising, terms and conditions, and apps of an array of fintech advisors, it appears that many of these tools offer advanced data analysis, machine learning, and even artificial intelligence to help consumers cut down on unnecessary spending, set aside money for savings, and use healthy nudges to improve their financial decisions. For instance, a fintech advisor may help a consumer automate savings “rules,” like rounding up charges and putting the difference into savings, enabling these small balances to accumulate over time or setting a small amount of money aside every time a consumer spends money on little splurges.

The early stages of innovation inevitably feature a lot of learning from trial and error. Fortunately, as the fintech ecosystem advances, there are useful experiences and good practices to draw upon from the evolution of the commercial internet. To begin with, one internet adage is that if a product is free, “you are the product.” In this vein, fintech advisors frequently offer free services to consumers and earn their revenue from the credit cards and other financial products that they recommend through lead generation.

Of course, many fintech advisors are not lead generators. Some companies offer fee-for-service models, with consumers paying a monthly fee for the product. Other companies are paid by employers, who then provide the products free of charge to their employees as an employee benefit. In these cases, they likely have quite different business models.

But for those services that do act as lead generators, there are important considerations about whether and how best to communicate information to the consumer about the nature of the recommendations being made. For instance, according to some reports, fintech advisors can make between $100 and $700 in lead generation fees for every customer that signs up for a credit card they recommend.

In many cases, a fintech advisor may describe their service as providing tailored advice or making recommendations as they would to friends and family. In such cases, a consumer might not know whether the order in which products are presented by a fintech assistant is based on the product’s alignment with his or her needs or different considerations. Different fintech advisors may order the lists they show consumers using different criteria. A product may be at the top of the advisor’s recommendations because the sponsoring company has paid the advisor to list it at the top, or the sponsoring company may pay the fintech assistant a high fee, contingent upon the consumer signing up for the product. Alternatively, a fintech advisor may change the order of the loan offers or credit cards based on the likelihood that the consumer will be approved. Moreover, in some cases, the absence of lead generation fees for a particular product may impact whether that product is on the list shown to consumers at all.

There appears to be a wide variety of practices regarding the prominence and placement of advertising and other disclosures relative to the advice and recommendations such firms provide. Overall, fintech assistants have increasingly improved the disclosures that explain to consumers how they get paid, but this is still a work in progress.

The good news is that these challenges are not new. The experience with internet search engines outside of financial products, such as Google, Bing, and Yahoo!, as well as with other product comparison sites, such as Travelocity and Yelp, may provide useful guidance. As consumers and businesses have adapted to the internet, we have, collectively, adopted norms and standards for how we can expect search and recommendation engines to operate. In particular, we generally expect that search results will be included and ranked based on what’s organically most responsive to the search–unless it is clearly labeled otherwise. Accordingly, when we search for a product, we now know to look for visual cues that identify paid search results, usually in the form of a text label like “Sponsored” or “Ad”, different formatting, and visually separating advertising from natural search results. Even when an endorsement is made in a brief Twitter update, we now expect disclosures to be clear and conspicuous.

As fintech advisors evolve to engage consumers in new ways, disclosure methodologies will no doubt be expected to adapt as well. For instance, some personal financial management tools now interact with consumers via text message. If consumers move to a world in which most of their interactions with their advisors occur via text-messaging “chatbots”–or voice communication–I am hopeful that industry, regulators, consumers, and other stakeholders will work together to adapt the norms to distinguish between advice and sponsored recommendations.

The Data Relationship

While the lead generation revenue model presents some familiar issues that are readily apparent, under the hood, fintech relationships raise even more complex issues for consumers in knowing who they are providing their data to, how their data will be used, for how long, and what to expect in the case of a breach or fraud. Let me briefly touch on each issue in turn.

Often, when a consumer signs up with a fintech advisor or other fintech app, they are asked to log into their bank account in order to link the fintech app with their bank account data. In reviewing apps’ enrollment processes, it appears that consumers are often shown log-in screens featuring bank logos and branding, prompting consumers to enter their online banking logins and passwords. In many cases, the apps note that they do not store the consumers’ banking credentials.

When the consumer logs on, he or she is often not interfacing with a banks’ computer systems, but rather, providing the bank account login and password to a data aggregator that provides services to the fintech app. In many cases, the data aggregator may store the password and login and then use those credentials to periodically log into the consumer’s bank account and copy available data, ranging from transaction data, to account numbers, to personally identifiable information. In other cases, things work differently under the hood. Some banks and data aggregators have agreed to work together to facilitate the ability to share data with outside developers in authorized ways. These agreements may delineate what types of data will be shared, and authorization credentials may be tokenized so that passwords are never stored by the aggregator.

It is often hard for the consumer to know what is actually happening under the hood of the financial app they are accessing. In most cases, the log in process does not do much to educate the consumer on the precise nature of the data relationship. Screen scraping usually invokes the bank’s logo and branding but infrequently shows the logo or name of the data aggregator. In reviewing many apps, it appears that the name of the data aggregator is frequently not disclosed in the fintech app’s terms and conditions, and a consumer generally would not easily see what data is held by a data aggregator or how it is used. The apps, websites, and terms and conditions of fintech advisors and data aggregators often do not explain how frequently data aggregators will access a consumer’s data or how long they will store that data.

Recognizing this is a relatively young field, but one that is growing fast, there are a myriad of questions about the consumer’s ability to opt out and control over data that will need to be addressed appropriately. In examining the terms and conditions for a number of fintech apps, it appears that consumers are rarely provided information explaining how they can terminate the collection and storage of their data. For instance, when a consumer deletes a fintech app from his or her phone, it is not clear this would guarantee that a data aggregator would delete the consumer’s bank login and password, nor discontinue accessing transaction information. If a consumer severs the data access, for instance by changing banks or bank account passwords, it is also not clear how he or she can instruct the data aggregator to delete the information that has already been collected. Given that data aggregators often don’t have consumer interfaces, consumers may be left to find an email address for the data aggregator, send in a deletion request, and hope for the best.

If things go wrong, consumers may have limited remedies. In reviewing terms, it appears that many fintech advisors include contractual waivers that purport to limit consumers’ ability to seek redress from the advisor or an underlying data aggregator. In some cases, the terms and conditions assert that the fintech developer and its third-party service providers will not be liable to consumers for the performance of or inability to use the services. It is not uncommon to see terms and conditions that limit the fintech adviser’s liability to the consumer to $100.

Traditionally, under the Electronic Funds Transfer Act and its implementing Regulation E, consumers have had protections to mitigate their losses in the event of erroneous or fraudulent transactions that would otherwise impact their credit and debit cards, such as data breaches. Those protections are not absolute, however. In particular, if a consumer gives another person an “access device” to their account and grants them authority to make transfers, then the consumer is “fully liable” for transfers made by that person, even if that person exceeds his or her authority, until the consumer notifies the bank. As the industry matures, the various stakeholders will need to develop a shared understanding of who bears responsibility in the event of a breach.

Shared Responsibility and Shared Benefit Moving Forward

So what can be done to make sure consumers have the requisite information and control to remain squarely in the driver’s seat? Establishing and implementing new norms is in the shared interest of all of the participants in the fintech stack. For instance, in the case of credit cards, mortgages, and many other products, it is often banks or parties closely affiliated with banks that pay fees to fintech advisors to generate leads for their products, pursuant to a contract. Through these contractual relationships with fintech advisors, banks have considerable influence in the lead generation relationship, including through provisions describing how a sponsored product should be described or displayed. Banks have a stake in ensuring that their vendors and third-party service providers act appropriately, that consumers are protected and treated fairly, and that the banks’ reputations aren’t exposed to unnecessary risk. Likewise, some of the leading speech-only financial products are currently credit card and bank products. Accordingly, banks have incentives to invest in innovating the way they disclose information to consumers, as they also invest in new ways of interacting with them.

As for consumers’ relationships with data aggregators, there’s an increasing recognition that consumers need better information about the terms of their relationships with aggregators, more control over what is shared, and the ability to terminate the relationship. We have spoken to data aggregators who recognize the importance of finding solutions to many of the complex issues involved with the important work of unlocking the potential of the banking stack to developers. And while there are some difficult issues in this space, other issues seem relatively straightforward. It shouldn’t be hard for a consumer to be informed who they are providing their credentials to. Consumers should have relatively simple means of being able to consent to what data are being shared and at what frequency. And consumers should be able to stop data sharing and request the deletion of data that have been stored.

Responsibility for establishing appropriate norms in the data aggregation space should be shared, with banks, data aggregators, fintech developers, consumers, and regulators all having a role. Banks and data aggregators are negotiating new relationships to determine how they can work together to provide consumers access to their data, while also ensuring that the process is secure and leaves consumers in the driver’s seat. In many cases, banks themselves were often the original customers of data aggregators, and many continue to use these services. According to public filings, more than half of the 20 largest banks are customers of data aggregators. The banks have an opportunity as customers of data aggregation services to ensure that the terms of data provision protect consumers’ data and handle it appropriately.

Regulators also recognize that there may be opportunities to provide more clarity about how the expectations about third-party risk management would work in this sector, as well as other areas experiencing significant technological change. Through external outreach and internal analysis, we are working to determine how best to encourage socially beneficial innovation in the marketplace, while ensuring that consumers’ interests are protected. We recognize the importance of working together and the potential to draw upon existing policies, norms, and principles from other spaces. Consumers may not fully understand the differences in regulations across financial products or types of financial institutions, or whether the rules change when they move from familiar search and e-commerce platforms to the fintech stack. Consumers, as well as the market as a whole, will benefit if regulators coordinate to provide more unified messages and support the development of standards that serve as a natural extension of the common-sense norms that consumers have come to expect in other areas of the commercial internet.

Conclusion

The combination of technologies that put vast computing power, rich data sets, and artificial intelligence onto simple smartphone apps together with important research into consumer financial behaviors has great potential to help consumers navigate their complex financial lives more effectively, but there are also important risks. I am hopeful that fintech developers, data aggregators, bank partners, consumers, and regulators will work together to keep consumers in the driver’s seat as we move forward with these new technologies. If we work together effectively toward this goal, the fintech stack may be able to offer enormous benefits to the consumers they aim to serve, while appropriately identifying and managing the risks.