The FED held their benchmark rate again, but the latest Federal Reserve FOMC statement contains a firm indication of rises ahead, if but slowly. Meantime, the balance sheet normalization is proceeding.

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in September indicates that the labor market has continued to strengthen and that economic activity has been rising at a solid rate despite hurricane-related disruptions. Although the hurricanes caused a drop in payroll employment in September, the unemployment rate declined further. Household spending has been expanding at a moderate rate, and growth in business fixed investment has picked up in recent quarters. Gasoline prices rose in the aftermath of the hurricanes, boosting overall inflation in September; however, inflation for items other than food and energy remained soft. On a 12-month basis, both inflation measures have declined this year and are running below 2 percent. Market-based measures of inflation compensation remain low; survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed, on balance.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. Hurricane-related disruptions and rebuilding will continue to affect economic activity, employment, and inflation in the near term, but past experience suggests that the storms are unlikely to materially alter the course of the national economy over the medium term. Consequently, the Committee continues to expect that, with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace, and labor market conditions will strengthen somewhat further. Inflation on a 12-month basis is expected to remain somewhat below 2 percent in the near term but to stabilize around the Committee’s 2 percent objective over the medium term. Near-term risks to the economic outlook appear roughly balanced, but the Committee is monitoring inflation developments closely.

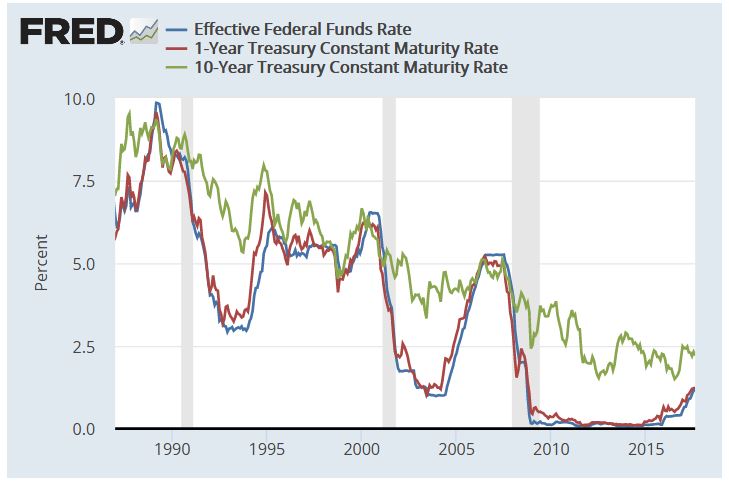

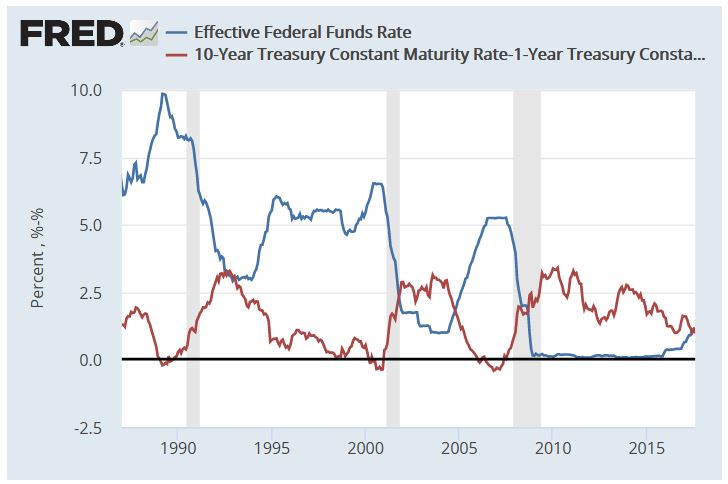

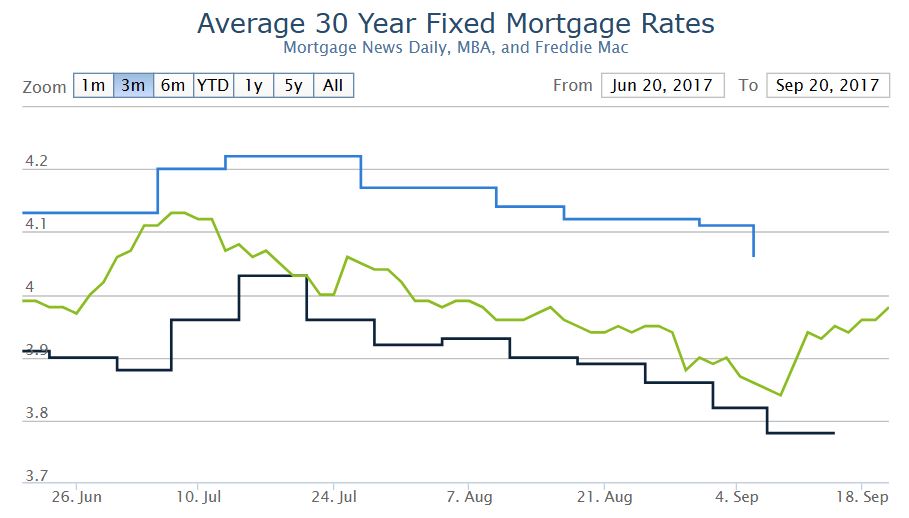

In view of realized and expected labor market conditions and inflation, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1 to 1-1/4 percent. The stance of monetary policy remains accommodative, thereby supporting some further strengthening in labor market conditions and a sustained return to 2 percent inflation.

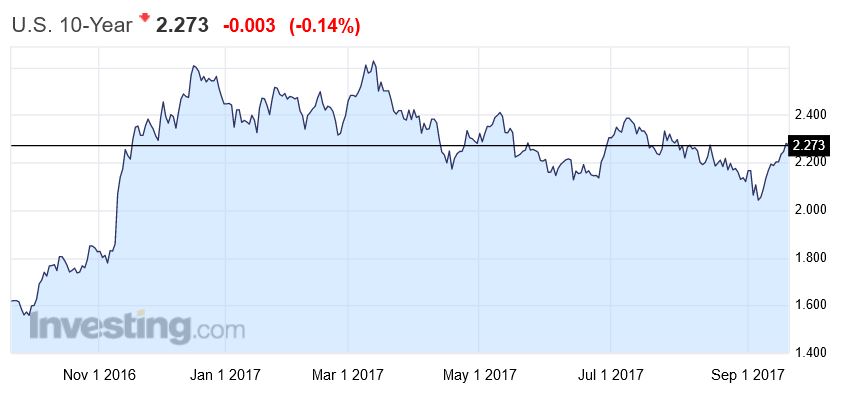

In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. The Committee will carefully monitor actual and expected inflation developments relative to its symmetric inflation goal. The Committee expects that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant gradual increases in the federal funds rate; the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run. However, the actual path of the federal funds rate will depend on the economic outlook as informed by incoming data.

The balance sheet normalization program initiated in October 2017 is proceeding.