From The St. Louis Fed on The Economy Blog.

People frequently scour economic data for clues about the direction of the economy. But could the many types of data cause confusion on what exactly the state of the economy is? A recent Economic Synopses essay examined some of this potential confusion.

Business Economist and Research Officer Kevin Kliesen noted that data essentially fall into two camps:

- Hard data, such as that from government statistical agencies used in constructing real gross domestic product (GDP)

- Soft data, such as business, consumer confidence and sentiment surveys, financial market variables, and labor statistics

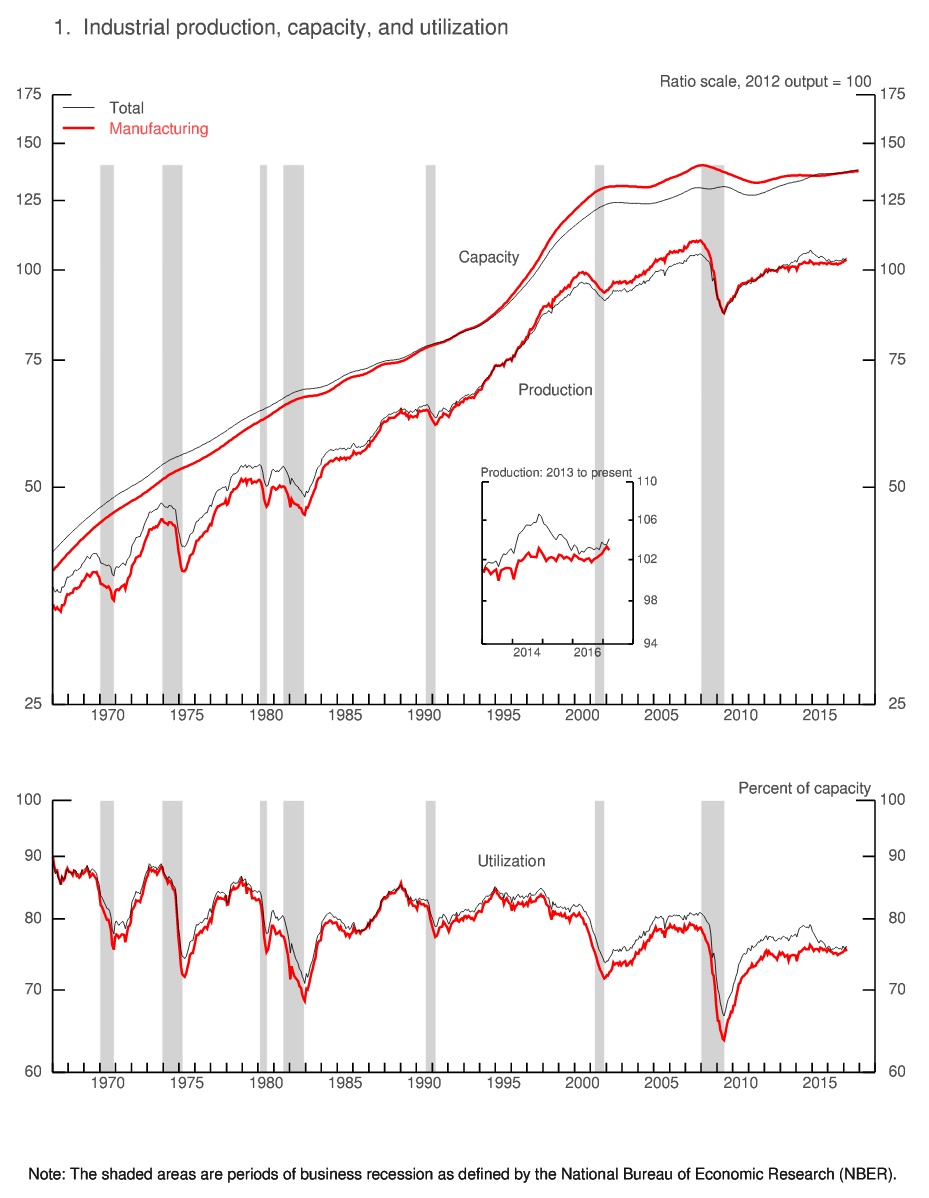

Kliesen crafted two index measures of these types of data, which can be seen in the figure below.1 He noted that these indexes could be useful for quantitatively showing how different types of data can influence forecasts of real GDP and, in turn, the expectations of policymakers.

“The indexes exhibit the normal cyclical behavior one would expect in the data: They increase in expansions and decrease in recessions,” Kliesen wrote.

He also noted that the hard data index showed stronger economic conditions from around the beginning of the recent recovery until late 2013. More recently, however, the soft data index is showing stronger economic conditions.

Effect on Forecasts

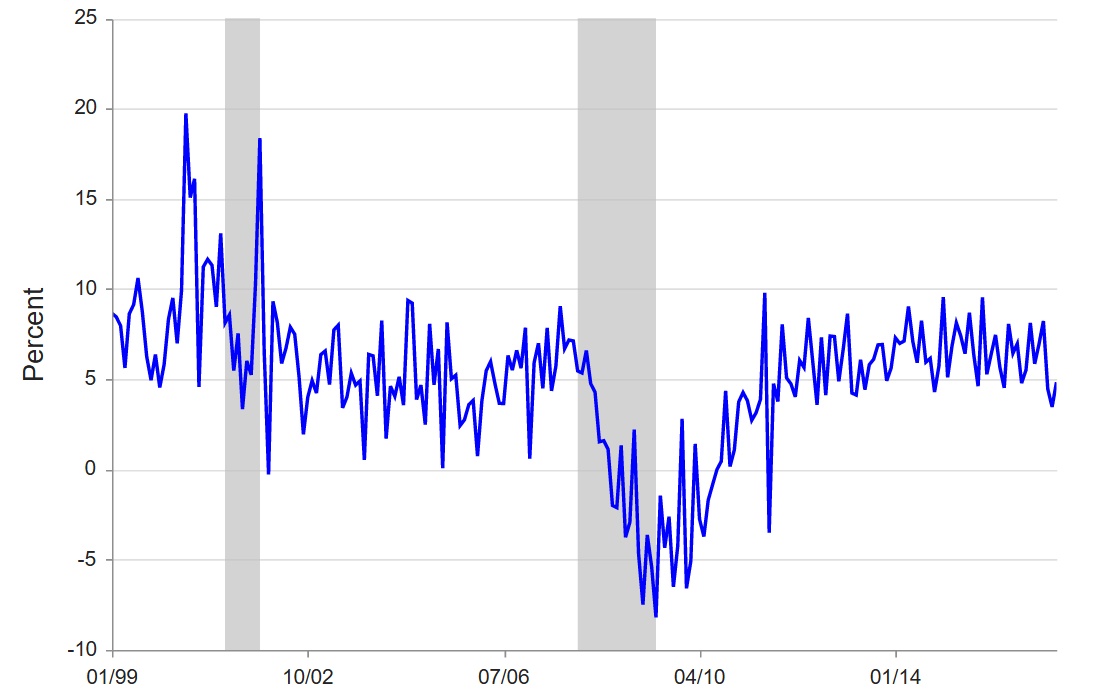

To show the possible effects of favoring one type of data when forecasting, Kliesen ran forecasts of monthly real GDP growth using only hard data and using only soft data:

- Forecasting growth using the hard data resulted in projected growth of a little more than 2 percent per quarter through the end of 2019.

- Using soft data, however, resulted in a peak of a little more than 4 percent in early 2018.

He then compared the results with the consensus forecasts found in the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) and the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC’s) Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). The results are in the table below.

Forecasts for Real GDP

Percent Changes, Q4/Q4Hard Data Soft Data SPF SEP 2017:Q4 1.9 3.9 2.3 2.1 2018:Q4 2.2 2.9 2.4 2.1 2019:Q4 2.4 2.5 2.6 1.9 NOTES: The SEP values are taken from the March 15 release and are Q4/Q4. The SPF values use average annual data and are taken from the Feb. 10 issue. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Kliesen concluded by saying that most forecasters and FOMC policymakers have relied more on hard data when forecasting. He wrote: “This is probably prudent, since the hard data flows are used in most macroeconomic forecasting models.”

He also noted: “However, as the upbeat forecasts from the soft data show, there appears to be some upside risk to the near-term forecast for real GDP growth. This upside risk likely reflects the widespread expectation of expansionary fiscal policy and a strengthening in global growth.”