She said new and highly fragmented “shared systems” may create unintended consequences even as they aim to address problems created by today’s siloed operations. Since distributed ledgers often involve shared databases, it will also be important to effectively manage access rights as information flows back and forth through shared systems.

It may require a trade-off between the privacy of trading partners and competitors on the one hand, and the ability to leverage shared transactions records for faster and cheaper settlement on the other hand.

Sound risk-management, resiliency, and recovery procedures will be necessary to address operational risks.

Financial products, services, and transactions lend themselves to successive waves of technological disruption because they can readily be represented as streams of numerical information ripe for digitization. However, as technological tools used by the industry change over time, it is important to keep sight of their impact on the public, whether it be on families seeking to own their own home, seniors seeking financial security, young adults seeking to invest in education and training, or small businesses attempting to smooth through volatile revenues and expenses.

Current developments in the digitization of finance are important and deserving of serious and sustained engagement on the part of policymakers and regulators. The Federal Reserve Board has established a multi-disciplinary working group that is engaged in a 360-degree analysis of fintech innovation. We are bringing together the best thinking across the Federal Reserve System, spanning key areas of responsibility, from supervision to community development, from financial stability to payments. As policymakers, we want to facilitate innovation where it has the potential to yield public benefit, while ensuring that risks are thoroughly understood and managed. That orientation may have different implications in the arena of consumer and small business finance, for instance, as compared with payment, clearing, and settlement in the wholesale financial markets.

Today, I will focus on newly emerging distributed ledger technologies and related protocols, which were inspired originally by Bitcoin, and their potentially important applications to payment, clearing, and settlement in the wholesale markets.

Successive waves of technological advance have swept through payment, clearing, and settlement over the past two centuries. In the 19th century, railroads and the telegraph helped improve speed and logistics. In the second half of the 20th century, computers were introduced to deal with the clearing of overwhelming volumes of paper checks and stock certificates stimulated by post-war growth. Starting at about the same time and continuing through today, new electronic networks have been established to allow high-speed computerized financial communication. As automation has evolved, payment, clearing, and settlement systems have been developed for conducting and processing transactions within and between firms. However, many of these systems have historically operated in silos, which can be hard to streamline or replace. In some areas, business processes may still rely heavily on manual or semi-automated procedures.

Over time, banks and other firms have organized various types of clearinghouses to coordinate clearing and settlement activities in order to reduce costs and risks. The adoption of multilateral clearing in the United States was a key organizational innovation that began with the founding of the New York Clearing House in the 1850s. This led to notable efficiencies and risk reduction in the clearing of checks. Multilateral clearing was also used early on to improve clearing in the securities and derivatives markets. By the 1970s, the United States turned to technologies based on the centralized custody and clearing of book-entry securities in order to respond to the paperwork crisis in the equities markets. Following the recent financial crisis, the United States–along with many other countries–expanded the scope of central clearing to help address problems in the bilateral clearing of derivatives contracts.

Today, the possible development and application of distributed ledger technology has raised questions about potentially far reaching changes to multilateral clearinghouses and the roles of financial institutions as intermediaries in trading, clearing, and settlement for their clients. In the extreme, distributed ledger technologies are seen as enabling a much larger universe of financial actors to transact directly with other financial actors and to exchange assets versus funds (that is, to “clear” and settle the underlying transactions) virtually instantaneously without the help of intermediaries both within and across borders. This dramatic reduction in frictions would be facilitated by distributed ledgers shared across various networks of financial actors that would keep a complete and accurate record of all transactions, and meet appropriate goals for transparency, privacy, and security.

At this stage, such a sea-change may sound like a remote possibility, particularly for the high volume and highly regulated clearing and settlement functions of the wholesale financial markets. But profound disruptions are not unprecedented in this arena. In the early 1960s, the use of computerized book-entry securities systems to streamline custody, clearing, and settlement in the securities markets may have seemed like a technologist’s pipe dream. But these technologies became an important part of industry-wide changes in the 1970s. Today we rely on these types of systems for the daily operation of the markets.

Given this backdrop, it is important to give promising technologies the serious consideration they merit, seek to understand their opportunities and risks, and actively engage in dialogue about their potential uses and evolution. At the Federal Reserve, we approach these issues from the perspective of policymakers safeguarding the public interest in safe and sound core banking institutions, financial stability, particularly as it pertains to the wholesale financial markets, and the security and efficiency of the payment system.

Distributed ledger technology was introduced for the transfer and record-keeping of Bitcoin and other digital currencies. The essential advantage of the technology is that it provides a credible way to transfer an asset without the need for trust in intermediaries or counterparties, much like a physical cash transaction. To do that, a transfer process must be able to credibly confirm that a sender of an asset is the owner and has enough of the asset to make the transfer to the receiver. This requires a secure system or protocol to transfer assets (the rails), protection against assets being transferred twice (the so-called double spend problem), and an immutable record of asset ownership that can be automatically and securely updated (the ledger). The tokenization of digital assets can facilitate the transfer process.

The genuinely innovative aspect of the technology combines a number of different core elements that support the transfer process and recordkeeping:

- Peer-to-peer networking and distributed data storage provide multiple copies of a single ledger across participants in the system so that all participants have a shared history of all transactions in the system.

- Cryptography, in the form of hashes and digital signatures, provides a secure way to initiate a transaction that helps verify ownership and the availability of the asset for transfer.

- Consensus algorithms provide a process for transactions to be confirmed and added to the single ledger.

While Bitcoin was originally associated with the concept of a universally available, publicly shared digital ledger technology without any central authority, many of the use cases that are currently under development and discussion rely on “permissioned” ledgers in which only permitted, known participants can validate transactions. These in turn can be either public or private in terms of access to the ledger.

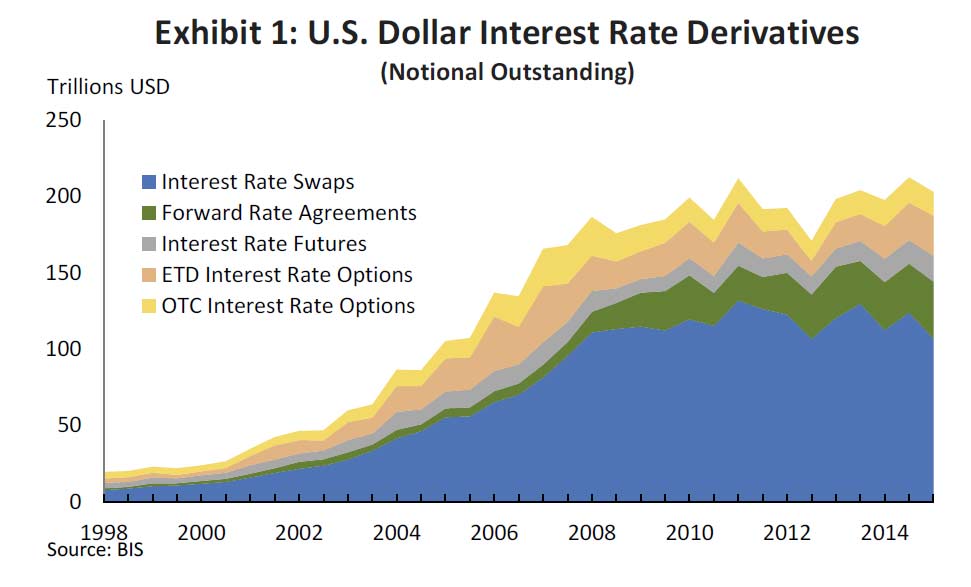

The resulting Internet of Value holds out the promise of addressing important frictions and reducing intermediation steps in the clearing and settlement process. For example, in cross-border payments, faster processing and reduced costs relative to current correspondent banking are cited as specific potential benefits. Reducing intermediation steps in cross-border payments may help reduce costs and counterparty risks and may additionally improve financial transparency.

In securities clearing and settlement, the potential shift to one master record shared among participants has some appeal. Having one immutable record may have the potential to reduce or even eliminate the need for reconciliation by avoiding duplicative records that have different details related to a transaction that is being cleared and settled. This also can lead to greater transparency, reduced costs, and faster securities settlement. Likewise, digital ledgers may improve collateral management by improving the tracking of ownership and transactions.

For derivatives, there is interest in the potential for digital ledger protocols to enable self-execution and possibly self-enforcement of contractual clauses, in the context of “smart contracts.”

As we engage with industry and stakeholders to assess the potential applications of digital ledger and related technologies in the payment, clearing, and settlement arena, we will be guided by the principles of efficiency, safety and integrity, and financial stability.

I want to close by remembering a simple point that central bankers and markets have learned through hard lessons over many years. The daily operation of markets and their clearing and settlement functions are built on trust and confidence. Market participants trust that clearing and settlement functions and institutions will work properly every day. Confidence has built over time that when market participants trade, accurate and timely clearing and settlement will follow. Any disruption to this confidence comes at great cost to market integrity and financial stability. This is a matter of fundamental public interest. In safeguarding the public interest, the first line of inquiry and protection will always rest with those closest to the technology innovations and to the organizations that consider adopting the technology. But regulators also should seek to analyze the implications of technology developments through constructive and timely engagement. We should be attentive to the potential benefits of these new technologies, and prepared to make the necessary regulatory adjustments if their safety and integrity is proven and their potential benefits found to be in the public interest.