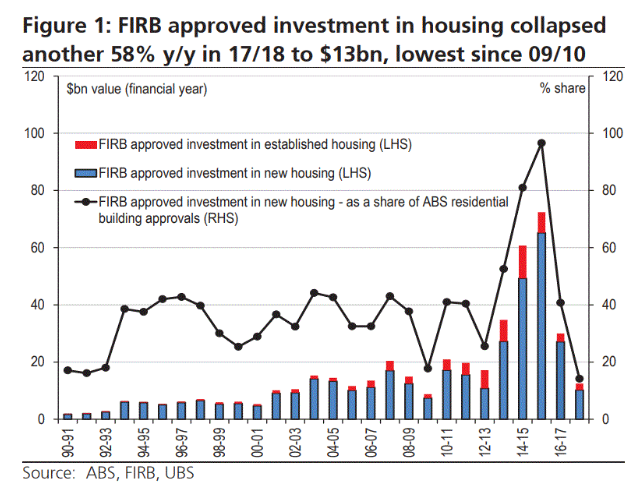

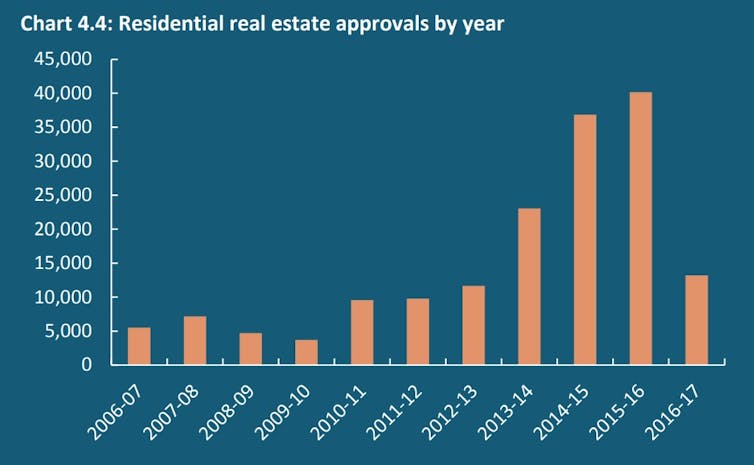

This is bad news for the property and financial industries, who are already feeling the pressure of weak household income growth, tighter lending restrictions on local borrowers, and a slowing in housing market activity in key Australian cities.

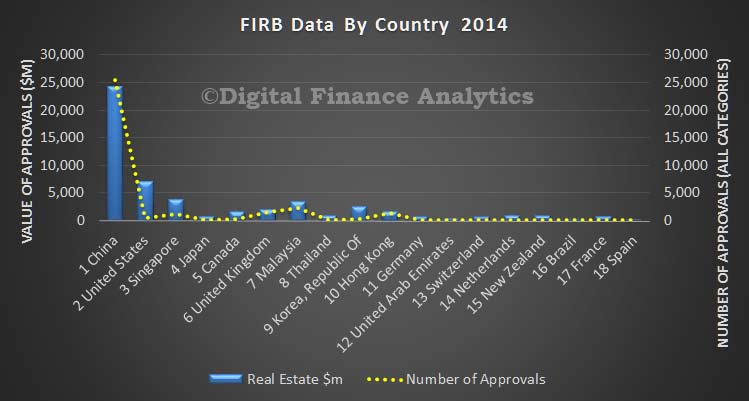

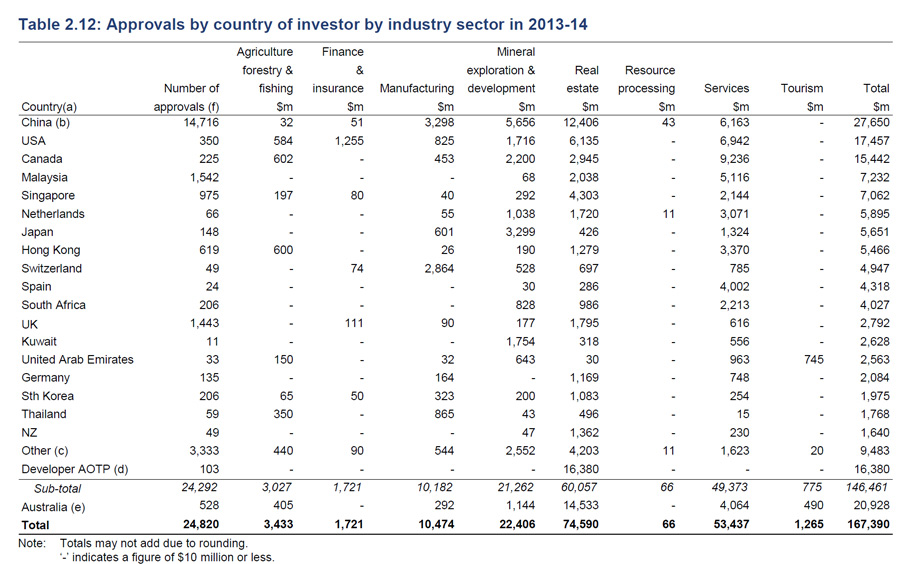

FIRB suggests that declining demand from China is a factor in the overall decline in overseas approvals. Chinese demand may have been weakened by a range of factors, including the new FIRB application fees, Chinese overseas direct investment capital controls, and the changing global economy.

But if the cycle is moving from boom towards bust, we have learned several things along the way.

Lesson 1: We still need more data

In 2014 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics undertook an inquiry into foreign investment in residential real estate. It acknowledged the growing public disquiet about the level of this foreign investment, adding that:

…there is no accurate or timely data that tracks foreign investment in residential real estate. No one really knows how much foreign investment there is in residential real estate, nor where that investment comes from.

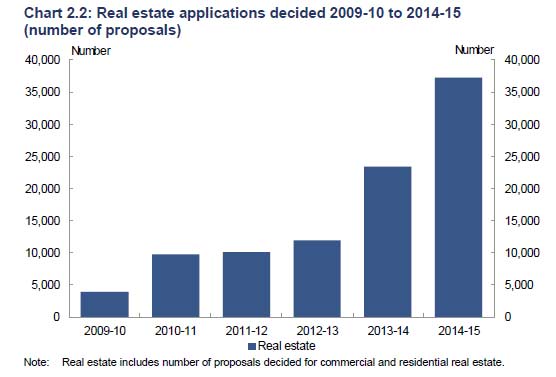

Four years on, FIRB is still flagging the limitations of data collection and analysis. Without fine-grained data, it’s hard to forecast how much, if at all, the injection of foreign capital can push up local house prices.

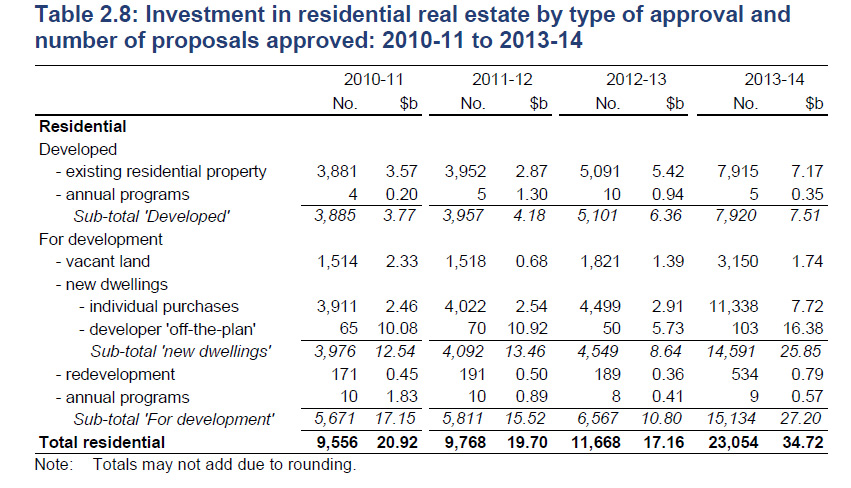

The latest figures come with a caveat. The approvals data represent potential investment, rather than actual investment. There are key differences between the two. Potential investors might, for example, seek approval for multiple properties while only intending to buy one of them.

We need the government to collect more extensive and detailed data on individual foreign real estate investment, and make it publicly available. This needs to cover more than approvals data at the city level, but data on investment levels in neighbourhoods or even individual housing developments.

Lesson 2: People on the property ladder are less hostile to foreign buyers

Data from Sydney reveals widespread concern about foreign investment. Almost 56% of Sydneysiders believed foreign investors should not be allowed to buy residential real estate in Sydney. Only 17% of respondents in our study thought the government’s regulation of foreign housing investment was effective.

Just over half of Sydneysiders say they would not want Chinese investors buying properties in their suburb. And 78% thought foreign investment was driving up housing prices in greater Sydney.

Yet those who have real estate investments were more likely to support foreign investment than those who don’t. This suggests that Sydneysiders with equity in the housing market, such as homeowners or investors, might view foreign buyers pushing up housing values as positive. And they might fear that the new decline in foreign investment might depress their assets.

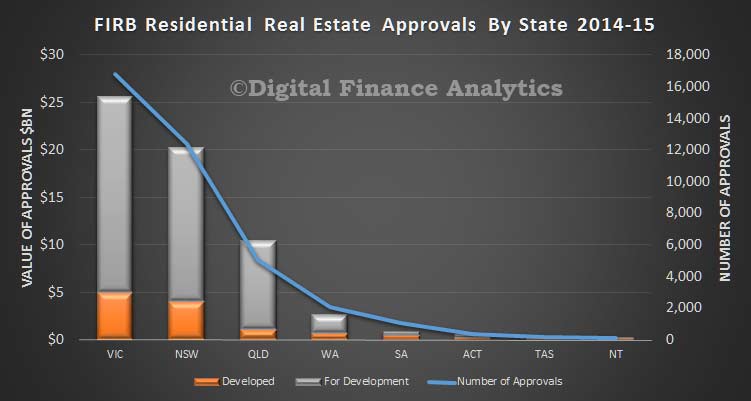

Lesson 3: Housing is built with specific buyers in mind

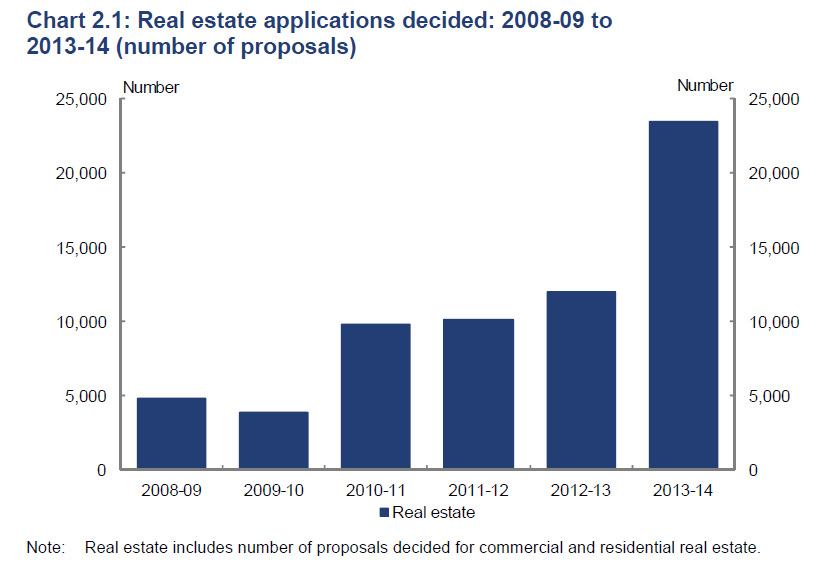

When Chinese real estate investment started to rise significantly in 2013-14, property developers scrambled to model this new emerging market. The real estate media rushed to map out where Chinese investors were keenest to buy, and how best to design and market property developments to this new foreign client base.

In early 2012, Larry Schlesinger quoted the demographer Bernard Salt as saying:

The growing numbers of Chinese and Indian migrants in Australia means property investors need to consider the cultural sensitivity of the residential property they purchase to ensure they maximise the resell value.

Between 2013 and 2017, property developers, both local and foreign, regularly contacted me to ask if I had any up-to-date research on foreign investors’ consumer preferences and market forecasts. I did not. But there was no shortage of advice out there, covering everything from feng shui-informed housing design to the key needs of foreign university students.

Some global real estate agents suggested to their clients that they could buy an Australian home to accommodate their child while they were studying at an Australian university, and then use the capital gain from the property sale to pay back the tuition fees.

Many property developers were formulating medium- to long-term development pipelines that included the foreign capital and consumer preferences of foreign investors. It is unclear, now, whether much of this housing stock will ever be built. If it is, will it suit the changing future needs of our cities, or address our ongoing housing affordability problems?

In other words, what sorts of properties will be left as the legacy of the recent foreign real estate investment mania?

Lesson 4: Racialised housing debates are simplistic and harmful

We need to take care not to conflate domestic Chinese-Australian buyers with international Chinese investors. Much of the media coverage of the new report features stereotyped images of Asian families buying an Australian home. But given the foreign investment rules and logistics involved, these pictures are far more likely to depict Chinese-Australians than foreigners.

Understanding the long-term migration and education plans of the investors is important too. Different investor groups will interact with the city in different ways, and their impact on society can be vastly different too. For example, super-rich absentee investors will have a different impact on neighbourhood life compared with that of middle-class migrants or international students.

If the federal government wants to court foreign investment, then better education about the possible risks and benefits of individual foreign real estate investment is needed. Our research suggests that the government’s pro-foreign investment stance must be accompanied with strategies to protect intercultural community relations in Australia.

Lesson 5: The boom-bubble-bust cycle goes on

In 1982, Maurice Daly wrote in his classic book Sydney Boom, Sydney Bust that the:

…fluctuation in property prices recorded for Sydney have been caused by the forces linking the city to the Australian economy and to the remainder of the world.

Daly charted the influx of foreign people and capital into Sydney between 1850 until 1981, as wealth was channelled through the financial services sector and into urban real estate. Along the way, he observed that one “group to attract the abuse of the general population were the Chinese”.

Domestic and foreign real estate investment have long been connected to the financial services industries, and the built environment is central to creating and storing surplus capital. Australian cities continue to be heavily influenced by global money today.

A key lesson is that domestic and foreign housing booms, bubbles and busts are thus better understood as cycles within our housing and financial system, rather than as a set of short-term ruptures to this system.

We need to think about the collective impacts of domestic and foreign real estate investment over the long-term in our cities if we are serious about addressing housing inequality.

Author: Dallas Rogers, Program Director, Master of Urbanism. School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney