The rating review focuses on the Australian-domiciled entities within each group and therefore does not encompass their overseas subsidiaries.

KEY RATING DRIVERS

VIABILITY RATINGS, IDRS AND SENIOR UNSECURED DEBT

The Long- and Short-Term IDRs and Stable Outlook on all four banks are driven by their Viability Ratings and reflect their dominant franchises in Australia and New Zealand as well as robust regulatory frameworks. Stable, transparent and traditional business models have proven effective in generating consistently strong profitability, while the banks maintained a conservative risk appetite relative to many international peers. High exposure to a heavily indebted household sector and increased focus on conduct related issues from authorities offset some of these strengths.

Australia’s banking regulator has been critical in helping the banking system manage rising macroeconomic risks – including historically high household debt and house prices, low interest rates and subdued wage inflation – through strengthening underwriting standards and increasing capital requirements. This has contributed to improving the banks’ ability to withstand a severe downturn in the housing market and household sector should it occur.

However, a severe downturn is not Fitch’s base case. We expect Australian house prices to remain high relative to international markets, with modest price rises in 2018. Overall, property prices should be supported by low interest rates and population growth. Offsetting this is high household debt, falling rental yields, increasing supply and rising dwelling completions.

Household debt could increase further, driven by historically low interest rates and high house prices, as residential mortgages make up almost 70% of household debt. Household debt reached 188% of disposable income at end-September 2017. Combined with low wage growth and high underemployment, this leaves households increasingly susceptible to higher interest rates and deteriorating labour market conditions.

The four major banks dominate their home markets. Their combined loans accounted for 80% of Australia’s total loans at end-December 2017 and 87% of New Zealand’s gross loans at end-September 2017. The banks have simplified their businesses and footprints with a strong focus on their core banking operations in Australia and New Zealand, or are in the process of doing so. They have well established and long standing competitive advantages and strong pricing power – manifested in strong earnings, profitability and balance sheets – which is likely to be maintained over the next two to three years.

The increased focus on conduct and competition by authorities has resulted in the establishment of a number of inquiries, the outcomes of which are uncertain. This could limit the banks’ growth potential and pricing power, pressuring the banks’ company profiles and ultimately affecting their ratings, although any significant impact appears unlikely to arise within the next two years.

Conduct related issues may also negatively affect our view of risk appetite and ratings if they indicate widespread failing within a bank’s risk-management framework. All four banks have faced a number of conduct related issues in the previous few years, although we continue to see these as isolated cases and believe risk-management frameworks remain robust. CBA has faced particular scrutiny following the August 2017 announcement of failures related to its anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing requirements. This, combined with a number of other infractions, prompted a regulatory inquiry into CBA’s governance, culture and accountability. Findings of systemic failure by this inquiry could pressure CBA’s ratings.

Disruptors, particularly in the digital sphere, are increasing in prominence, although they remain a small part of the system. The disruptors also pose some longer-term risks to the franchises of the major banks, although management appears to be addressing this pro-actively with strong IT investments, which we expect to continue.

Fitch expects the banks’ credit risk appetite to remain tight. We believe the banks have robust risk management frameworks. Regulatory intervention and oversight provide an additional restriction on the banks’ ability to take larger risks by weakening underwriting standards. Fitch expects additional regulatory scrutiny on serviceability testing in 2018, particularly around the assessment of borrowers’ expenses, which should further strengthen underwriting. Limits on growth rates for investor and interest-only loans has seen the pace of growth in these products slow; we see these as riskier types of mortgages relative to amortising owner-occupier mortgages. The growth rates of these products could be further curtailed by proposals by the regulator to have them carry higher risk-weights than amortising owner-occupier loans.

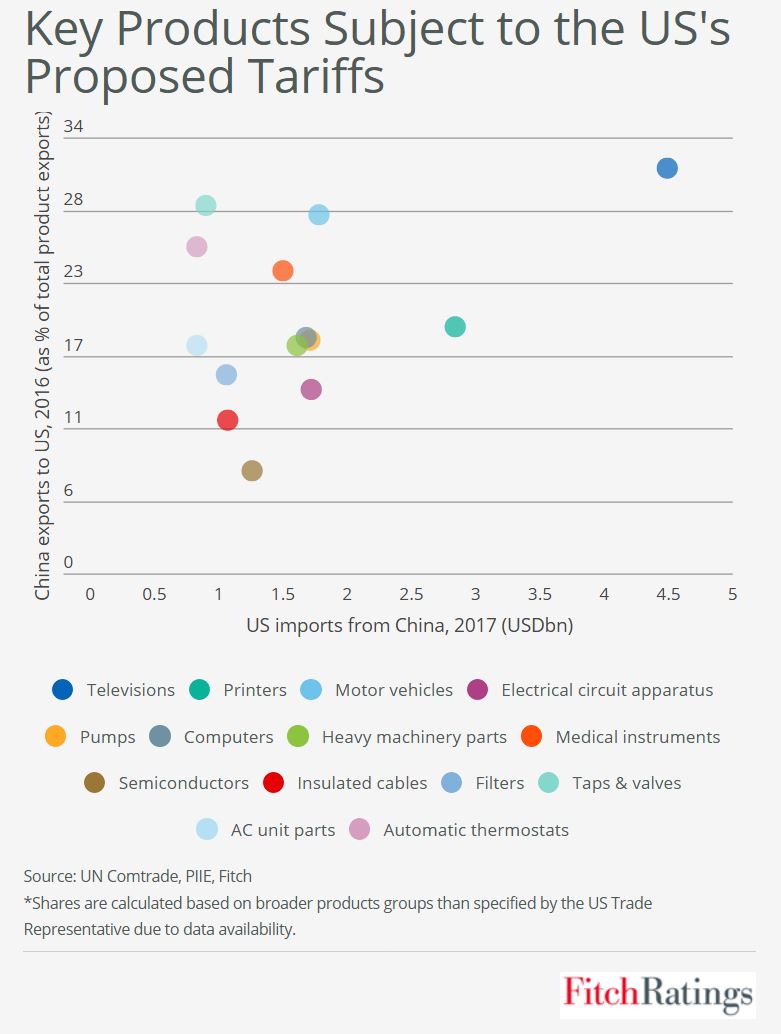

We believe the banks’ asset quality is likely to remain a strength relative to similarly rated international peers, although some weakening is possible through 2018. Large losses are not probable without an economic shock, such as may occur if there was a sharper-than-expected slowdown in China. Industries, such as retail, may come under pressure from soft consumer spending due to low wage growth, high household debt and competition from online retailers. However, given the banks’ limited exposure to the retail sector, our base case means any deterioration should be manageable.

Fitch believes the Australian major banks are well-capitalised and will meet Australian Prudential Regulation Authority requirements for “unquestionably strong” capital ratios well ahead of the proposed deadline. Implementation of the final Basel III framework should not be onerous either. Comparisons of risk-weighted ratios with international peers are difficult due to the Australian regulator’s tougher capital standards relative to many other jurisdictions. These include, among other factors, higher minimum risk-weightings for residential mortgages through Pillar 1 and larger capital deductions.

Funding remains a weakness relative to similarly rated international peers. Fitch expects the banks to continue relying on wholesale markets in the medium-term, although strengthened liquidity positions and swapping borrowings into the functional currency – usually either Australian or New Zealand dollars – help offset some of this risk. The banks’ funding profiles are also supported by access to contingent liquidity through the central bank, if needed, and the likelihood that they would benefit from a flight to quality in a stress environment.

Profitability growth is likely to slow in 2018, reflecting Fitch’s expectations for slower asset growth, competition for assets and deposits, higher funding costs and a rise in loan-impairment charges from cyclical lows. Cost management will remain a focus, but could be affected by continued technology investment and regulatory-related costs.