In his budget reply speech this week, Opposition leader Bill Shorten said Labor had “very grave concerns about retrospective changes” to superannuation being proposed by the government. The superannuation industry has been even more vociferous. But labelling the changes as “retrospective” in this case is a furphy.

For a decade, some older savers have benefited from superannuation tax breaks that did little to help younger generations. Understandably, they want to keep receiving these benefits. But they are wrong to claim the government’s proposed superannuation changes are retrospective simply because they adversely affect the future returns on their savings.

“Retrospectivity”, a legal concept, applies if government changes the legal consequences of things that happened in the past.

The Commonwealth government proposes two changes to superannuation rules in the 2016 budget. First, funds in excess of A$1.6 million in pension phase (when the fund holder pays no tax on earnings) will have to be moved into a separate account that pays 15% tax on earnings. In effect, retirees will pay no tax on the earnings of assets up to $1.6 million, and 15% tax on earnings after that.

Second, the budget proposes a new lifetime limit of A$500,000 on post-tax contributions to super. This includes any contributions made between 2007 (when reliable records begin) and budget night. If someone has already contributed more than this, there will be no penalty, but they will not be able to contribute any more from their post tax income.

The rationale for both changes is that they align superannuation more closely with its purpose of supplementing or replacing the Age Pension. A person with $1.6 million in a superannuation account, or a person contributing more than half a million from post tax income (in addition to pre-tax contributions), is going to be well over the asset limit for a part Age Pension ($805,000 for a couple home-owner).

The objection is that these changes retrospectively affect superannuation investments made in the past. But lots of changes affect investments made in the past, and no-one suggests they are retrospective. If I bought shares in a company yesterday, I expect that the future earnings on these assets will be subject to my marginal income tax rate. But if my income tax rates change, I would not expect that the old tax rate to be grandfathered to apply to all my future earnings.

This is the appropriate analogy for proposed changes to the earnings of superannuation accounts in excess of $1.6 million. The mere fact that no tax was paid on earnings in the past does not imply that earnings in the future are entitled to be tax free.

The retrospectivity argument is even weaker for the new cap on post-tax contributions. The only constraint is on additional contributions in the future. True, this is based on the amount that has already been contributed, but no adverse consequence flows from historic contributions; the change merely limits future contributions. To draw another analogy, it is not retrospective to change the asset test for the Age Pension merely because assets accumulated in the past are now taken into account for assessing future Age Pension payments.

Alternatively, we can analyse this problem using ethical concepts that are reflected in the legal doctrine of “estoppel”. This applies if a person reasonably relies on a promise of another party, and because of that reliance is injured or damaged.

The proposed changes do not fall foul of this doctrine.

Those who were induced to put more money into super would be a long way in front even if they had paid 15% tax on all earnings in retirement. Most contributions to superannuation are made from pre-tax earnings, and only taxed at 15%. Even those on very high incomes who pay tax of 30% on their contributions are still getting a discount of more than 15 per cent compared to post-tax savings. Once in the super fund, the earnings on those contributions are only taxed at 15% rather than at marginal income tax rates. The only people who could possibly have lost money contributing more to superannuation are those with taxable incomes less than A$19,000 a year – below the income tax-free threshold. If any of them have accumulated more than $1.6 million in superannuation, the ATO should probably be asking them some questions.

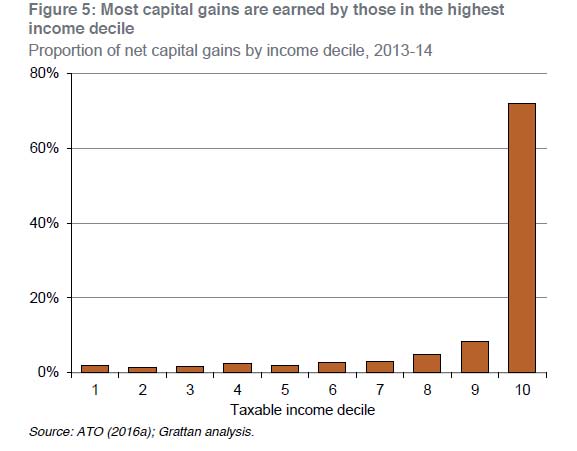

Superannuation tax concessions have been absurdly generous to older people on high incomes for over a decade. They have not served the purposes of the system. They are one of the major reasons why households over the age of 65 (unlike households aged between 25 and 64) are paying less income tax in real terms today than they did 20 years ago, even though their workforce participation rates and real wages have jumped. Misguided claims about retrospectivity should not be used as cover so that this older generation continues to gain unjustifiable benefits that will now be denied to younger generations.

Author: , Chief Executive Officer, Grattan Institute