Choice, the consumer group, has called for consumers to be able to cancel their credit cards immediately online, rather than jump through the hoops which the banks currently prescribe.

They recently reviewed the cancellation policies of the big four and found a distinct lack of easy cancellation options.

What? No online cancellation?

Instead of being able to cancel your card online and quickly cut ties with the debt monster, the banks force you to call, write a letter or visit a branch in person.

Meanwhile, almost all other banking services – including applying for a credit card and having it approved – are available online these days.

To us, it looks like a blatant attempt to keep you attached to your credit card and keep the debt clock rolling. That’s why we’ve been pushing to have the tactic abolished since August 2015.

Our review comes as the banks are set to face a Parliamentary Inquiry on Friday this week, and it follows attempts by ANZ and Westpac to ward off credit card criticism by promising to cut interest rates on some “low rate” cards.

Jumping through hoops

Here’s what the banks require if you want to cancel your credit card.

ANZ

- Call or write to ANZ.

- Return the card: “ANZ will only cancel the credit card when the account holder has returned it to ANZ cut diagonally in half (including any chip on the card) or has taken all reasonable steps to return it to ANZ”.

- Any additional funds will be returned by bank cheque.

NAB

- Call, write “or otherwise advise NAB in a manner acceptable to NAB”.

- Cut the card diagonally in half.

- Additional funds will be returned by bank cheque. NAB will charge its “usual fee” for issuing the cheque. Cash out is only available for amounts under $5.

Westpac

- Call, write or visit a Westpac branch.

- Promise to destroy the card.

- Additional funds are paid by bank cheque or directed into another account by direct debit.

CBA

No instructions are provided for card cancellations in the CBA credit card ‘conditions of use’ document. Customer service representatives instructed CHOICE to call the credit card team to cancel, which can only be contacted Monday to Friday, 9.00am–5.30pm.

Chasing fees and interest

“In the age of online banking if defies belief that ANZ, NAB, Westpac and Commonwealth all require you to call or email them when seeking to cancel a credit card,” says CHOICE head of campaigns and policy Erin Turner.

“It seems clear that the big banks’ ‘go slow’ on card cancellations is about protecting revenue from interest and fees, with data showing the big banks slug consumers with an average annual fee of $146 compared to just $58 through a mutual or customer-owned banks.

“Unfortunately, getting stuck paying excessive credit card interest is only one of the traps consumers face, with many of us paying excessive annual fees when we fail to cancel a card.”

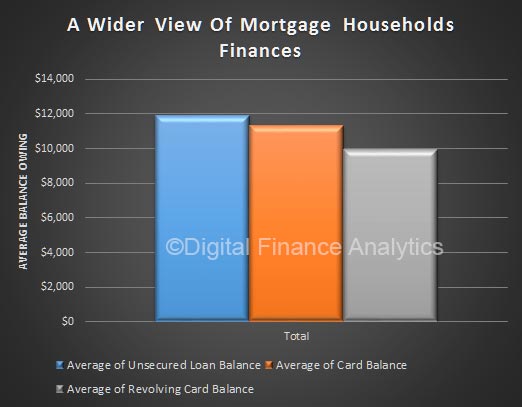

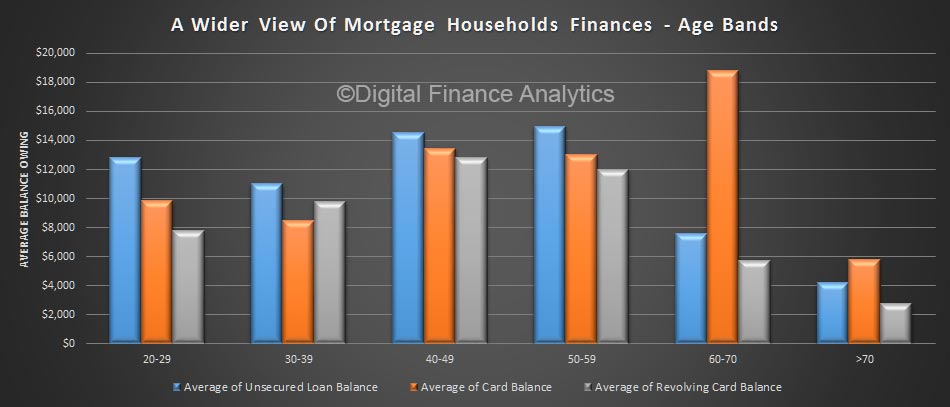

The national collective credit card debt hovers at a staggering $32 billion or so at the moment (about $4300 per cardholder). If you’re one of those consumers who’ve gotten in over your head, it’s generally a good idea to cancel the offending card once you’ve climbed out of debt.

That would be doubly true if you happen to have a card from one of the big four banks: CBA, ANZ, NAB and Westpac. Their standard interest rates are among the highest. And their so-called low-interest cards aren’t that much better – or at least not better enough.