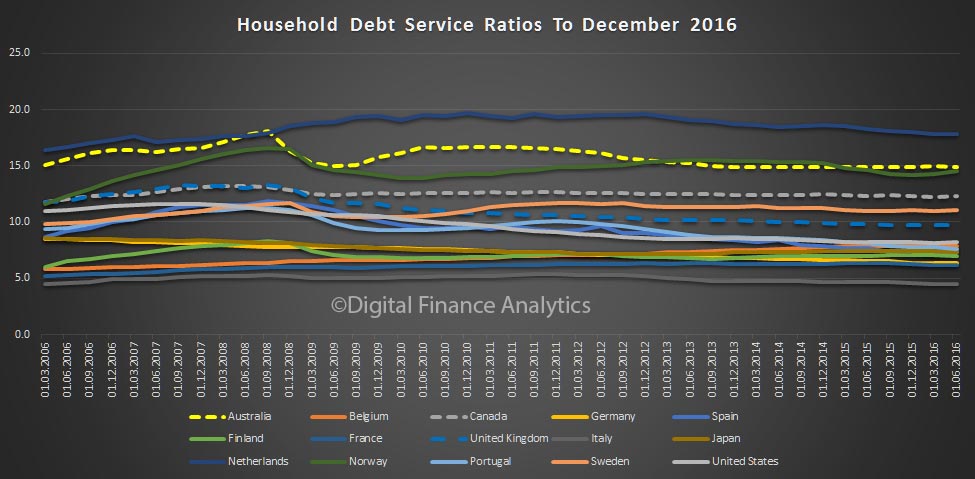

The OECD has once again warned that rising borrowing costs could wreak havoc on global property markets this year.

Chief economist of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Catherine Mann, told the UK’s The Telegraph that property prices had soared in Canada, New Zealand and Sweden in a way “not consistent with a stable real estate market”.

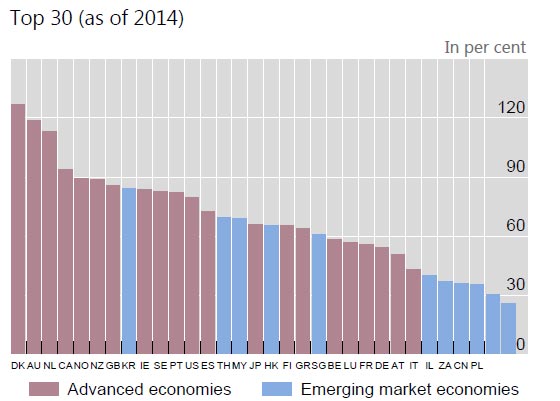

What she didn’t mention is that the OECD’s own research puts Australia in the middle of that pack based on house-price-to-income ratios – making it at least as likely to be affected by the US Federal Reserve-led rise in global interest rates.

In its last economic outlook, the Paris-based think tank rated Sweden at 22 per cent above its long-term price-to-income ratio, Australia 29.4 per cent above, Canada at 30.5 per cent and New Zealand at 31.9 per cent.

In the UK market, where that ratio is only 21.3 per cent, the London market is already cooling rapidly thanks in part to Brexit uncertainty.

Ms Mann said it would be “interesting” to see “who bears the burden – who bears the adjustment cost”.

The Australian story

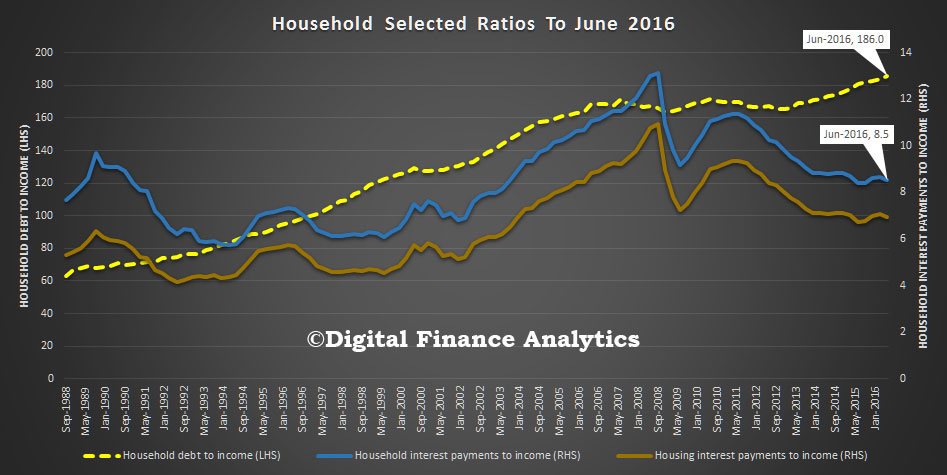

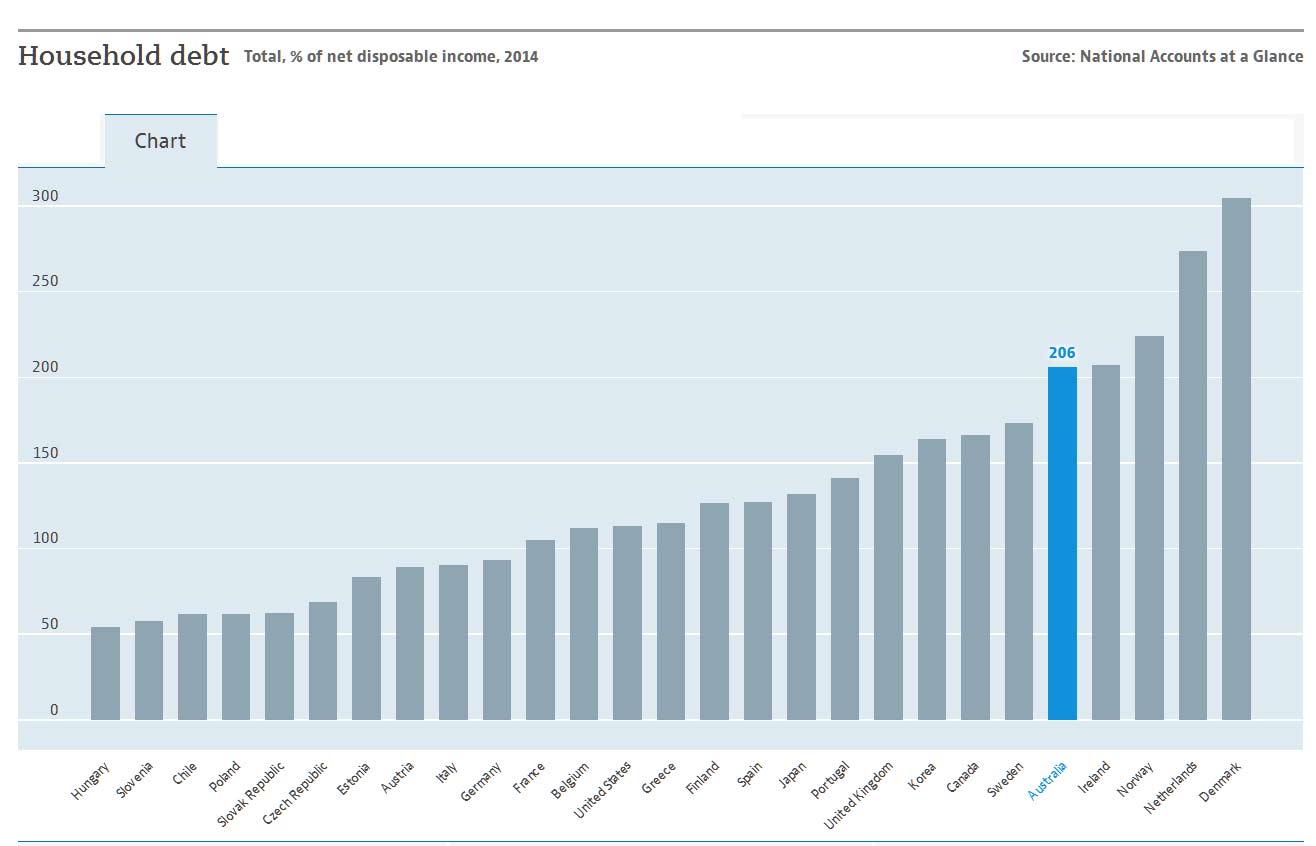

The same question needs to be asked in Australia, in light of our eye-watering levels of household debt.

There are mixed opinions as to whether the Reserve Bank will cut official rates again this year, but even if it does it will be fighting a tide of rising rates in wholesale funding markets.

Those rates affect a third of our banks’ borrowing costs and are likely to force more out-of-cycle mortgage rate hikes.

Who will bear that pain?

To understand what Catherine Mann, the OECD’s chief economist, means by “adjustment costs”, both asset prices and lending rates have to be taken into account.

That’s because banks lend money based on two main criteria: the income the borrower has to service debt at a given interest rate, and the likelihood of the asset increasing or decreasing in value.

Just before the global financial crisis hit, some Australian lenders were offering mortgages at loan-to-valuation ratios of up to 107 per cent.

Re-mortgaging to cover extravagant spending is coming to an end. Photo: Getty

Re-mortgaging to cover extravagant spending is coming to an end. Photo: Getty

They were so confident the market would continue rising, that they were happy for the safety buffer of equity to build up in the months or years after the loan was made.

Likewise, serviceability ratios were stretched to the limit at lenders such as Bankwest, because the mining boom was inflating wage packets relatively quickly.

The GFC changed all that. The lenders that were pushing those ratios too far, such as Bankwest, St George and Rams Home Loans, came close to collapse in 2009 and were snapped up at bargain prices by the bigger banks.

While the worst excesses of the GFC have not been repeated, banks and borrowers have once again become too comfortable with the idea that rising property prices and wages will get overstretched borrowers out of trouble.

Ms Mann is essentially warning us not to get too comfortable, as the era of ultra-low interest rates comes to an end.

Debt as ‘income’

To illustrate the point, I’ll go back to the example of the “completely disorganised” borrower described to me by a lending manager last year.

“[What’s] interesting in terms of the implications … is who bears the burden,” said Catherine Mann. Photo: Getty

“[What’s] interesting in terms of the implications … is who bears the burden,” said Catherine Mann. Photo: Getty

Such borrowers, he said, would bumble along with maxed-out credit cards, a personal loan for their last holiday, a leased car, and a fairly opulent lifestyle overall.

In a rising market, they could, and did, remortgage every few years and use equity in their home to pay for their extravagance.

What’s changed? Well firstly, many Australian households are seeing a big slowdown in the capital growth of their homes.

The latest all-cities average dwelling price from CoreLogic, released on Tuesday, shows a national increase of 10.8 per cent over 12 months.

However, that is overwhelmingly concentrated in Sydney (up 15.5 per cent) and Melbourne (13.7 per cent).

For “disorganised” borrowers living in Perth, where values have actually fallen 4.3 per cent, there’ll be no more remortgaging to pay off their other debts – the era of equity withdrawal is over, for some years at least.

Higher mortgage costs will make the end of debt-funded spending an even bigger shock. Photo: Getty

Higher mortgage costs will make the end of debt-funded spending an even bigger shock. Photo: Getty

The situation is similar in Darwin, where prices rose less than inflation in the past 12 months (0.9 per cent), or Brisbane where prices were just a bit ahead of inflation (3.6 per cent).

If out-of-cycle rate increases start to bite into their budgets, households in many areas are facing a double-whammy – no more debt-financed consumption, plus higher monthly outgoings just to keep a roof over their heads.

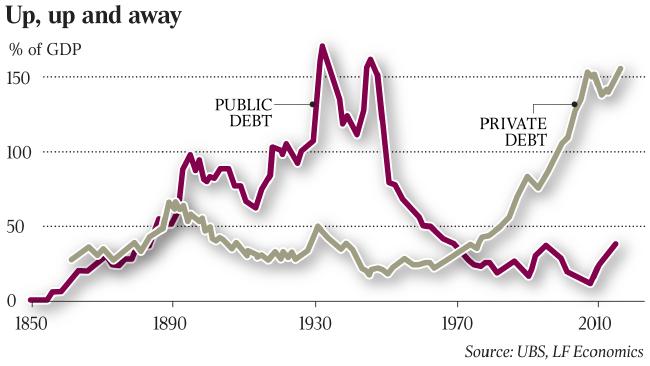

As economist Steve Keen has argued for years, household consumption is financed by two things: wages, plus the net change in debt.

We are now going into an era when a growing number of households will have only their wages to spend.

With wage growth at record lows and mortgage rate increases on the medium-term horizon, for the over-indebted that’s going to come as quite a shock.

This is explained by massive amounts of borrowing for housing (both owner occupied and investment) whilst unsecured personal debt is not growing. Such high household debt, even with low interest rates sucks spending from the economy, and is a brake on growth. The swelling value of home prices, and paper wealth (as well as growing bank balance sheets) do not really provide the right foundation for long term real sustainable growth.

This is explained by massive amounts of borrowing for housing (both owner occupied and investment) whilst unsecured personal debt is not growing. Such high household debt, even with low interest rates sucks spending from the economy, and is a brake on growth. The swelling value of home prices, and paper wealth (as well as growing bank balance sheets) do not really provide the right foundation for long term real sustainable growth.