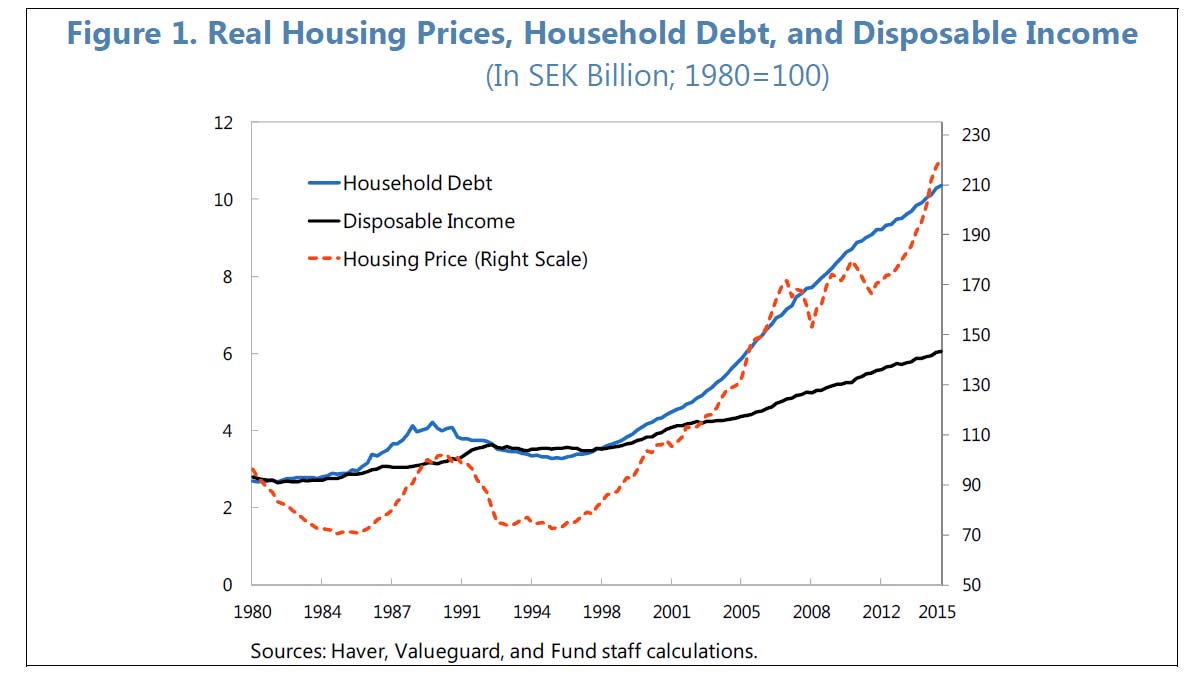

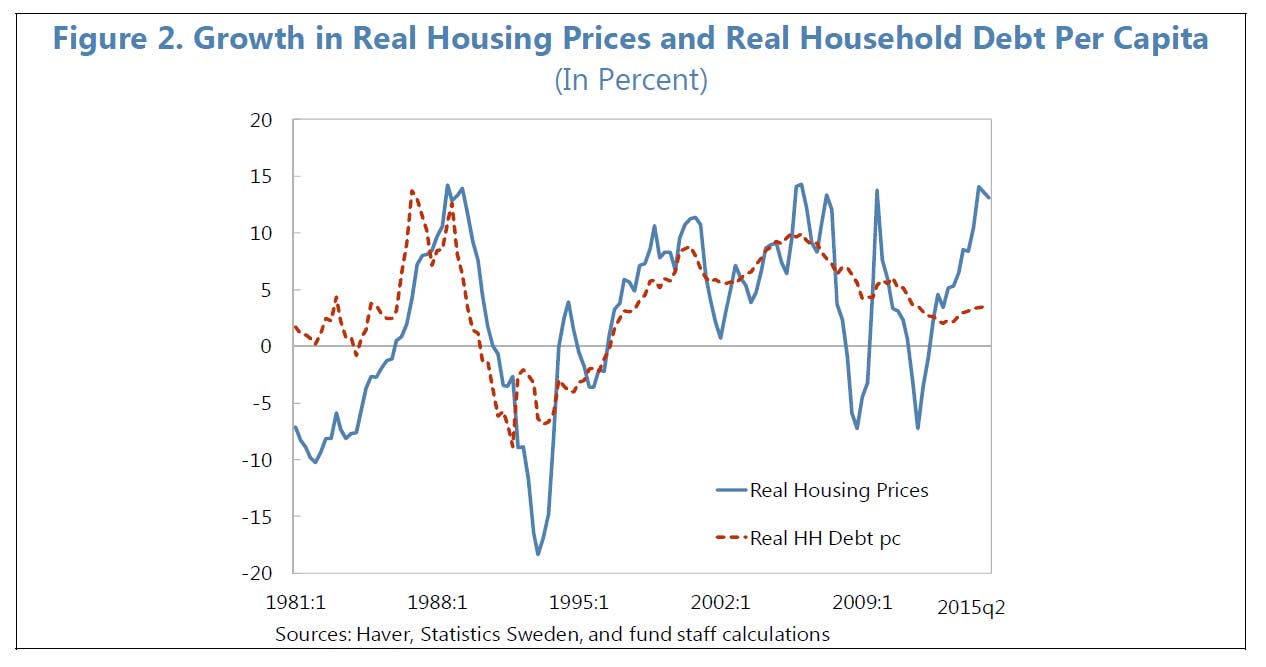

An interesting IMF working paper “Mitigating the Deadly Embrace in Financial Cycles: Countercyclical Buffers and Loan-to-Value Limits” examines the limitations of Basel III in the home loan market, and makes the point that the risk-weighted focus, even with enhancement, does not cut the mustard especially in a rising or falling property market. Indeed, there is a “deadly embrance” between housing, house prices, and bank mortgages which naturally leads to housing boom and bust cycles, which can be very costly for the economy and difficult for central banks to manage. They find that macroprudential measures may assist, but even then the deadly embrace remains.

The financial history of the last eight centuries is replete with devastating financial crises, mostly emanating from large increases in financial leverage. The latest example, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, saw the unwinding of a calamitous run-up in leverage by banks and households associated with the housing market. As a result, the financial supervision community has acknowledged that microprudential regulations alone are insufficient to avoid a financial crisis. They need to be accompanied by appropriate macroprudential policies to avoid the build-up of systemic risk and to weaken the effects of asset price inflation on financial intermediation and the buildup of excessive leverage in the economy.

The Basel III regulations adopted in 2010 recognize for the first time the need to include a macroprudential overlay to the traditional microprudential regulations. Beyond the requirements for capital buffers, and leverage and liquidity ratios, Basel III regulations include CCBs between 0.0 and 2.5 percent of risk-weighted assets that raise capital requirements during an upswing of the business cycle and reduce them during a downturn. The rationale is to counteract procyclical-lending behavior, and hence to restrain a buildup of systemic risk that might end in a financial crisis. Basel III regulations are silent, however, about the implementation of CCBs and their cost to the economy, leaving it to the supervisory authorities to make a judgment about the appropriate timing for increasing or lowering such buffers, based on a credit-to-GDP gap measure. This measure, however, does not distinguish between good versus bad credit expansions and is irrelevant for countries with significant dollar lending, where exchange rate fluctuations can severely distort the credit-to-GDP gap measure.

One of the limitations of Basel III regulations is that they do not focus on specific, leverage-driven markets, like the housing market, that are most susceptible to an excessive build-up of systemic risk. Many of the recent financial crises have been associated with housing bubbles fueled by over-leveraged households. With hindsight, it is unlikely that CCBs alone would have been able to avoid the Global Financial Crisis, for example.

For this reason, financial supervision authorities and the IMF have looked at additional macroprudential policies. For the housing market, three additional types of macroprudential regulations have been implemented: 1) sectoral capital surcharges through higher risk weights or loss-given-default (LGD) ratios;3 2) LTV limits; and 3) caps on debt-service to income ratios (DSTI), or loan to income ratios (LTI). Use of such macroprudential regulations has mushroomed over the last few years in both advanced economies and emerging markets. At end-2014, 23 countries used sectoral capital surcharges for the housing market, and 25 countries used LTV limits. An additional 15 countries had explicit caps on DSTI or LTI caps. The experience so far has been mixed.in a sample of 119 countries over the 2000-13 period find that, while macroprudential policies can help manage financial cycles, they work less well in busts than in booms. This result is intuitive in that macroprudential regulations are generally procyclical and can therefore be counterproductive during a bust when bank credit should expand to offset the economic downturn.

Macroprudential regulations are often directed at restraining bank credit, especially to the housing market. They do not, however, take into account the tradeoffs between mitigating the risks of a financial crisis on the one side and the cost of lower financial intermediation on the other. In addition, given that these measures are generally procyclical, they can accentuate the credit crunch during busts. More generally, an analytical foundation for analyzing these tradeoffs has been lacking. MAPMOD has been designed to help fill this analytical gap and to provide insights for the design of less procyclical macroprudential regulations.

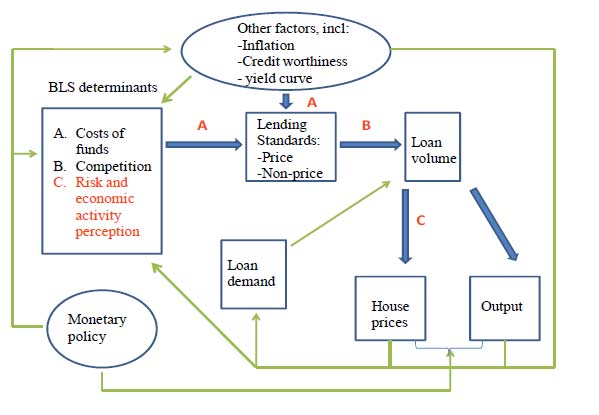

The MAPMOD Mark II model in this paper includes an explicit housing market, in which house prices are strongly correlated with banks’ credit supply. This corresponds to the experience prior and during the Global Financial Crisis. This deadly embrace between bank mortgages, household balance sheets, and house prices can be the source of financial cycles. A corollary is that the housing market is only partially constrained by LTV limits as the additional availability of credit itself boosts house prices, and thus raises LTV limits.

The starting point of the MAPMOD framework is the factual observation that, in contrast to the loanable funds model, banks do not wait for additional deposits before increasing their lending. Instead, they determine their lending to the economy based on their expectations of future profits, conditional on the economic outlook and their regulatory capital. They then fund their lending portfolio out of their existing deposit base, or by resorting to wholesale funding and debt instruments. Banks actively seek new opportunities for profitable lending independently of the size or growth of their deposit base—unless constrained by specific regulations.

In MAPMOD, Mark II, we extend the original model by introducing an explicit housing market. We use the modular features of the model to analyze partial equilibrium simulations for banks, households, and the housing market, before turning to general equilibrium results. This incremental approach sheds light on the intuition behind the model and simulation results.

The housing market is characterized by liquidity-constrained households that require financing to buy houses. A house is an asset that provides a stream of housing services to households. The value of a house to each household is the net present value of the future stream of housing services that it provides plus any capital gain/loss associated with future changes in house prices. We define the fundamental house price households are willing to pay to buy a house the price that is consistent with the expected income/productivity increases in the economy. If prices go above the fundamental house price reflecting excessive leverage, we refer to this as an inflated house price. The supply of houses for sale in the market is assumed to be fixed each period. House prices are determined by matching buyers and sellers in a recursive equilibrium with expected house prices taken as given. We abstract from many real-world complications such as neighborhood externalities, geographical location, square footage or other forms of heterogeneity.

Bank financing plays a critical role in the determination of house prices in the model. If banks provide a larger amount of mortgages on an expectation of higher household income in the future, demand for housing will go up, thus inflating house prices. Conversely, if banks reduce their loan exposure to the housing market, demand for houses in the economy will be reduced, leading to a slump in house prices. House prices therefore move with the credit cycle in MAPMOD, Mark II, just as in the real world.

Nonperforming loans and foreclosures in the housing market occur when households are faced with an idiosyncratic, or economy-wide, shock that affects their current LTV or LTI characteristics. Banks will seek to reduce the likelihood of losses by requiring a sufficiently high LTV ratio to cover the cost of foreclosure. But they will not be able to diversify away the systemic risk of a general fall in house prices in the economy. Securitization of mortgages in MAPMOD is not allowed. And even if banks were able to securitize mortgages, other agents in the economy would need to carry the systemic risk of a sharp fall in house prices. At the economy-wide level, the systemic risk associated with the housing market is therefore not diversifiable. The evidence from the Global Financial Crisis on securitization and credit default swaps confirms that this is the case, regardless of who holds mortgage-backed securities.

This paper presented a new version of MAPMOD (Mark II) to study the effectiveness of macroprudential regulations. We extend the original MAPMOD by explicitly modeling the housing market. We show how lending to the housing market, house prices, and household demand for housing are intertwined in the model in a what we call a deadly embrace. Without macroprudential policies, this naturally leads to housing boom and bust cycles. Moreover, leverage-driven cycles have historically been very costly for the economy, as shown most recently by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–09.

Macroprudential policies have a key role to play to limit this deadly embrace. The use of LTV limits for mortgages in this regard is ineffective, as these limits are highly procyclical, and hold back the recovery in a bust. LTV limits that are based on a moving average of historical house prices can considerably reduce their procyclicality. We considered a 5 year moving average, but the length of the moving average used should probably vary based on the specific circumstances of each housing market.

CCBs may not be an effective regulatory tool against credit cycles that affect the housing market in particular, as banks may respond to higher/lower regulatory capital buffers by reducing/increasing lending to other sectors of the economy.

A combination of LTV limits based on a moving average and CCBs may effectively loosen the deadly embrace. This is because such LTV limits would attenuate the housing market credit cycle, while CCBs would moderate the overall credit cycle. Other macroprudential policies, like DSTI and LTI caps, may also be useful in this respect, depending on the specifics of the financial landscape in each country. It is, however, important to recognize that all these macroprudential policies come at a cost of dampening both good and bad credit cycles. The cost of reduced financial intermediation should be taken into account when designing macroprudential policies.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.