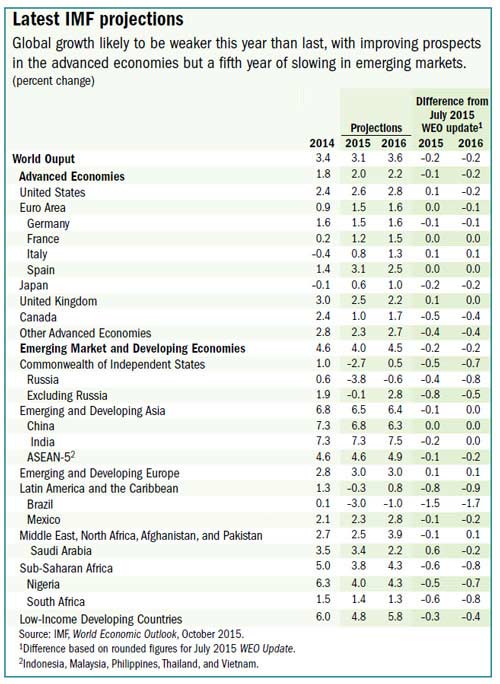

The latest World Economic Outlook, just released, contains a lower growth projection of 3.4 percent in 2016 and 3.6 percent in 2017 and so raising actual and potential output through a mix of demand support and structural reforms is even more urgent.

Recent Developments

In 2015, global economic activity remained subdued. Growth in emerging market and developing economies—while still accounting for over 70 percent of global growth—declined for the fifth consecutive year, while a modest recovery continued in advanced economies. Three key transitions continue to influence the global outlook: (1) the gradual slowdown and rebalancing of economic activity in China away from investment and manufacturing toward consumption and services, (2) lower prices for energy and other commodities, and (3) a gradual tightening in monetary policy in the United States in the context of a resilient U.S. recovery as several other major advanced economy central banks continue to ease monetary policy.

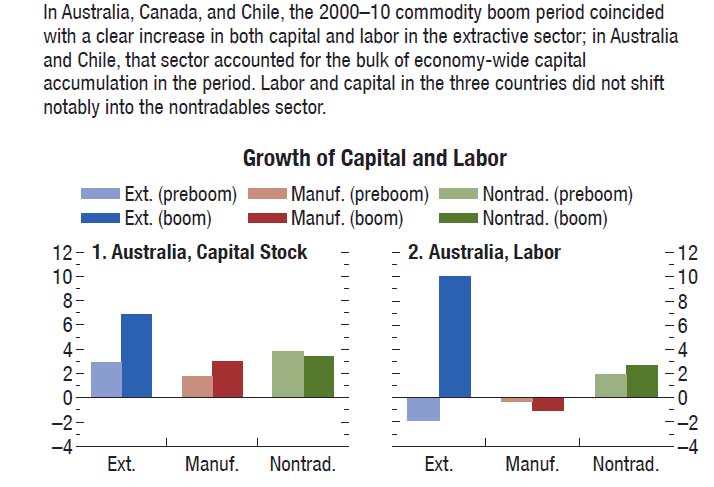

Overall growth in China is evolving broadly as envisaged, but with a faster-than-expected slowdown in imports and exports, in part reflecting weaker investment and manufacturing activity. These developments, together with market concerns about the future performance of the Chinese economy, are having spillovers to other economies through trade channels and weaker commodity prices, as well as through diminishing confidence and increasing volatility in financial markets. Manufacturing activity and trade remain weak globally, reflecting not only developments in China, but also subdued global demand and investment more broadly—notably a decline in investment in extractive industries. In addition, the dramatic decline in imports in a number of emerging market and developing economies in economic distress is also weighing heavily on global trade.

Oil prices have declined markedly since September 2015, reflecting expectations of sustained increases in production by Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) members amid continued global oil production in excess of oil consumption.1 Futures markets are currently suggesting only modest increases in prices in 2016 and 2017. Prices of other commodities, especially metals, have fallen as well.

Lower oil prices strain the fiscal positions of fuel exporters and weigh on their growth prospects, while supporting household demand and lowering business energy costs in importers, especially in advanced economies, where price declines are fully passed on to end users. Though a decline in oil prices driven by higher oil supply should support global demand given a higher propensity to spend in oil importers relative to oil exporters, in current circumstances several factors have dampened the positive impact of lower oil prices. First and foremost, financial strains in many oil exporters reduce their ability to smooth the shock, entailing a sizable reduction in their domestic demand. The oil price decline has had a notable impact on investment in oil and gas extraction, also subtracting from global aggregate demand. Finally, the pickup in consumption in oil importers has so far been somewhat weaker than evidence from past episodes of oil price declines would have suggested, possibly reflecting continued deleveraging in some of these economies. Limited pass-through of price declines to consumers may also have been a factor in several emerging market and developing economies.

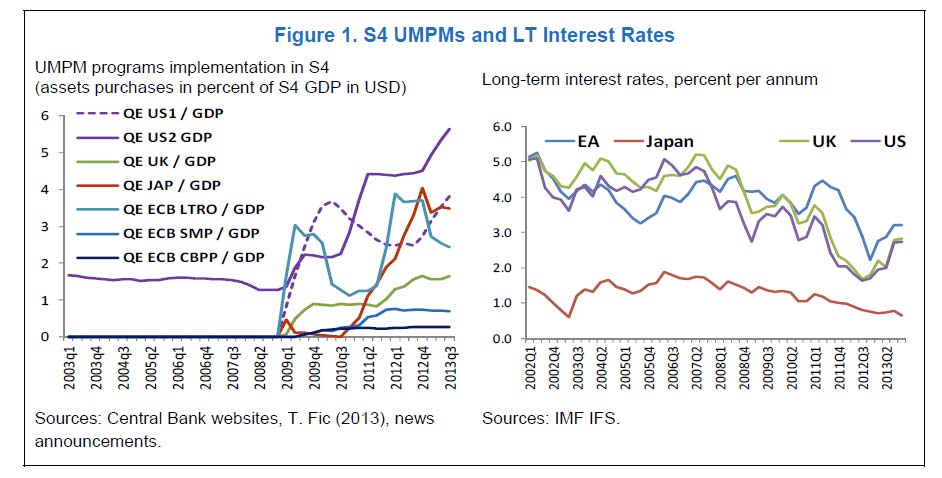

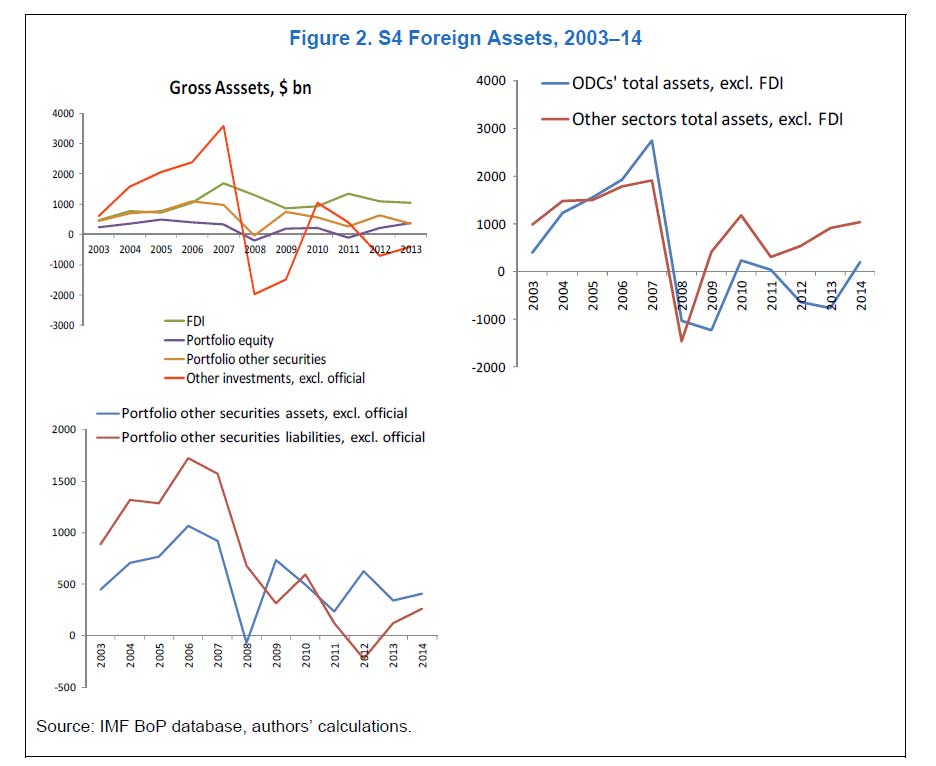

Monetary easing in the euro area and Japan is proceeding broadly as previously envisaged, while in December 2015 the U.S. Federal Reserve lifted the federal funds rate from the zero lower bound. Overall, financial conditions within advanced economies remain very accommodative. Prospects of a gradual increase in policy interest rates in the United States as well as bouts of financial volatility amid concerns about emerging market growth prospects have contributed to tighter external financial conditions, declining capital flows, and further currency depreciations in many emerging market economies.

Headline inflation has broadly moved sideways in most countries, but with renewed declines in commodity prices and weakness in global manufacturing weighing on traded goods’ prices it is likely to soften again. Core inflation rates remain well below inflation objectives in advanced economies. Mixed inflation developments in emerging market economies reflect the conflicting implications of weak domestic demand and lower commodity prices versus marked currency depreciations over the past year.

The Updated Forecast

Global growth is projected at 3.4 percent in 2016 and 3.6 percent in 2017.

Advanced Economies

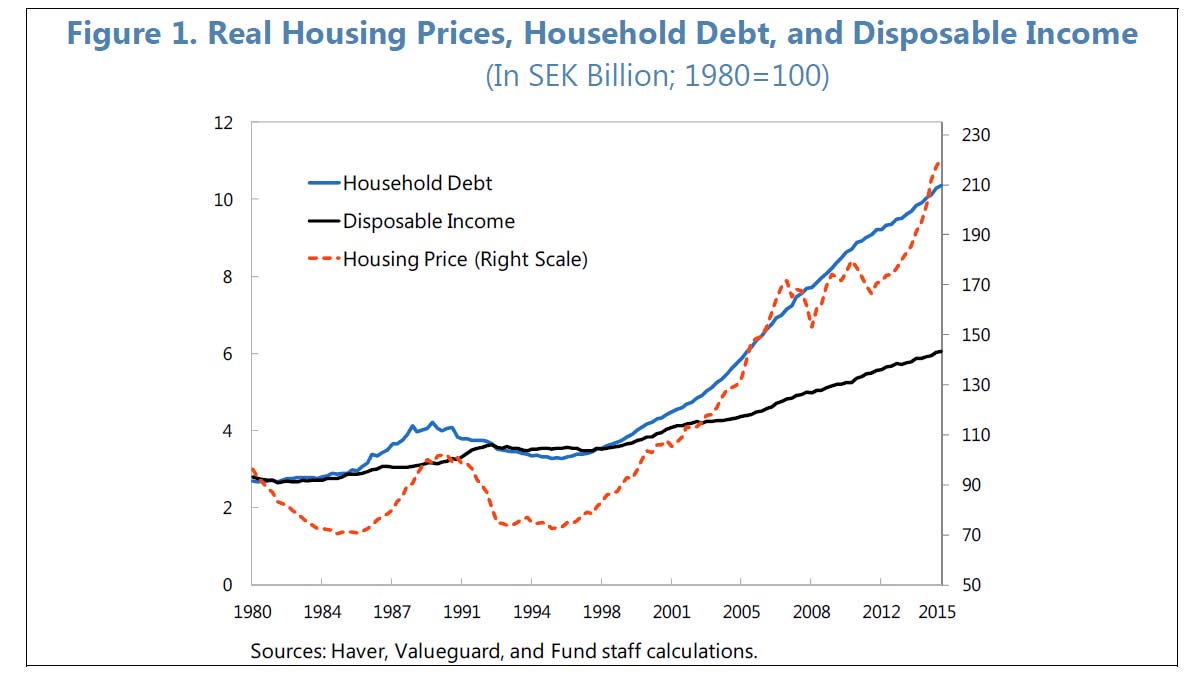

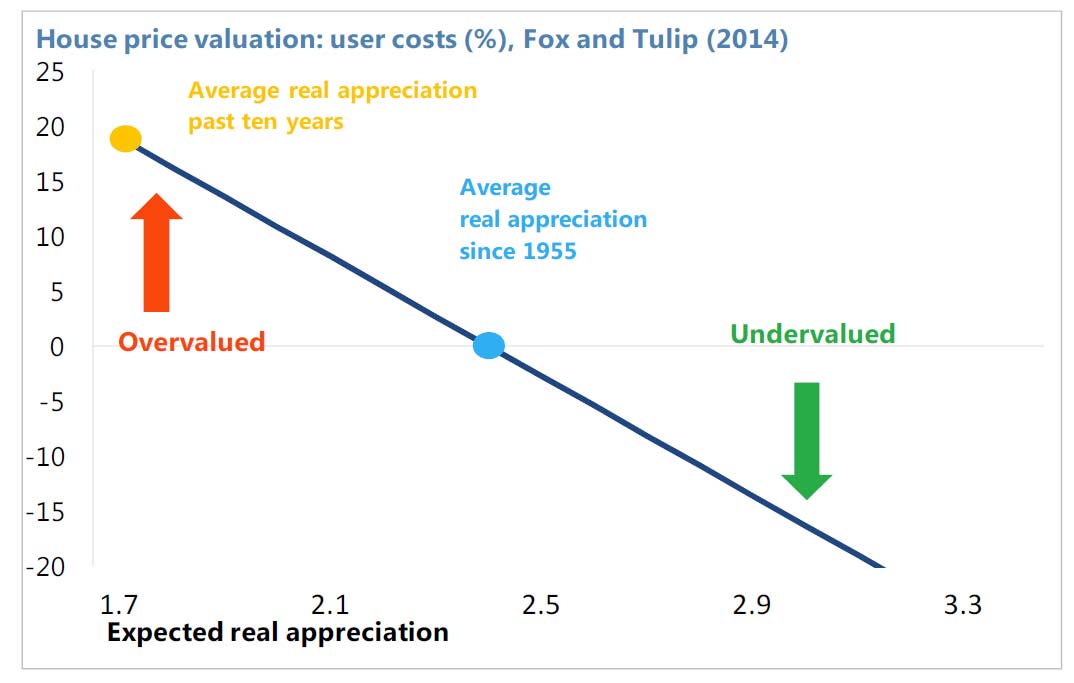

Growth in advanced economies is projected to rise by 0.2 percentage point in 2016 to 2.1 percent, and hold steady in 2017. Overall activity remains resilient in the United States, supported by still-easy financial conditions and strengthening housing and labor markets, but with dollar strength weighing on manufacturing activity and lower oil prices curtailing investment in mining structures and equipment. In the euro area, stronger private consumption supported by lower oil prices and easy financial conditions is outweighing a weakening in net exports. Growth in Japan is also expected to firm in 2016, on the back of fiscal support, lower oil prices, accommodative financial conditions, and rising incomes.

Emerging Market and Developing Economies

Growth in emerging market and developing economies is projected to increase from 4 percent in 2015—the lowest since the 2008–09 financial crisis—to 4.3 and 4.7 percent in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

- Growth in China is expected to slow to 6.3 percent in 2016 and 6.0 percent in 2017, primarily reflecting weaker investment growth as the economy continues to rebalance. India and the rest of emerging Asia are generally projected to continue growing at a robust pace, although with some countries facing strong headwinds from China’s economic rebalancing and global manufacturing weakness.

- Aggregate GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean is now projected to contract in 2016 as well, albeit at a smaller rate than in 2015, despite positive growth in most countries in the region. This reflects the recession in Brazil and other countries in economic distress.

- Higher growth is projected for the Middle East, but lower oil prices, and in some cases geopolitical tensions and domestic strife, continue to weigh on the outlook.

- Emerging Europe is projected to continue growing at a broadly steady pace, albeit with some slowing in 2016. Russia, which continues to adjust to low oil prices and Western sanctions, is expected to remain in recession in 2016. Other economies of the Commonwealth of Independent States are caught in the slipstream of Russia’s recession and geopolitical tensions, and in some cases affected by domestic structural weaknesses and low oil prices; they are projected to expand only modestly in 2016 but gather speed in 2017.

- Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa will see a gradual pickup in growth, but with lower commodity prices, to rates that are lower than those seen over the past decade. This mainly reflects the continued adjustment to lower commodity prices and higher borrowing costs, which are weighing heavily on some of the region’s largest economies (Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa) as well as a number of smaller commodity exporters.

Forecast Revisions

Overall, forecasts for global growth have been revised downward by 0.2 percentage point for both 2016 and 2017. These revisions reflect to a substantial degree, but not exclusively, a weaker pickup in emerging economies than was forecast in October. In terms of the country composition, the revisions are largely accounted for by Brazil, where the recession caused by political uncertainty amid continued fallout from the Petrobras investigation is proving to be deeper and more protracted than previously expected; the Middle East, where prospects are hurt by lower oil prices; and the United States, where growth momentum is now expected to hold steady rather than gather further steam. Prospects for global trade growth have also been marked down by more than ½ percentage point for 2016 and 2017, reflecting developments in China as well as distressed economies.

Risks to the Forecast

Unless the key transitions in the world economy are successfully navigated, global growth could be derailed. Downside risks, which are particularly prominent for emerging market and developing economies, include the following:

- A sharper-than-expected slowdown along China’s needed transition to more balanced growth, with more international spillovers through trade, commodity prices, and confidence, with attendant effects on global financial markets and currency valuations.

- Adverse corporate balance sheet effects and funding challenges related to potential further dollar appreciation and tighter global financing conditions as the United States exits from extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy.

- A sudden rise in global risk aversion, regardless of the trigger, leading to sharp further depreciations and possible financial strains in vulnerable emerging market economies. Indeed, in an environment of higher risk aversion and market volatility, even idiosyncratic shocks in a relatively large emerging market or developing economy could generate broader contagion effects.

- An escalation of ongoing geopolitical tensions in a number of regions affecting confidence and disrupting global trade, financial, and tourism flows.

Commodity markets pose two-sided risks. On the downside, further declines in commodity prices would worsen the outlook for already-fragile commodity producers, and increasing yields on energy sector debt threaten a broader tightening of credit conditions. On the upside, the recent decline in oil prices may provide a stronger boost to demand in oil importers than currently envisaged, including through consumers’ possible perception that prices will remain lower for longer.

Policy Priorities

With the projected pickup in growth being once again weaker than previously expected and the balance of risks remaining tilted to the downside, raising actual and potential output through a mix of demand support and structural reforms is even more urgent.

In advanced economies, where inflation rates are still well below central banks’ targets, accommodative monetary policy remains essential. Where conditions allow, near-term fiscal policy should be more supportive of the recovery, especially through investments that would augment future productive capital. Fiscal consolidation, where warranted by fiscal imbalances, should be growth friendly and equitable. Efforts to raise potential output through structural reforms remain critical. Although the structural reform agenda should be country specific, common areas of focus should include strengthening labor market participation and trend employment, tackling legacy debt overhang, and reducing barriers to entry in product and services markets. In Europe, where the tide of refugees is presenting major challenges to the absorptive capacity of European Union labor markets and testing political systems, policy actions to support the integration of migrants into the labor force are critical to allay concerns about social exclusion and long-term fiscal costs, and unlock the potential long-term economic benefits of the refugee inflow.

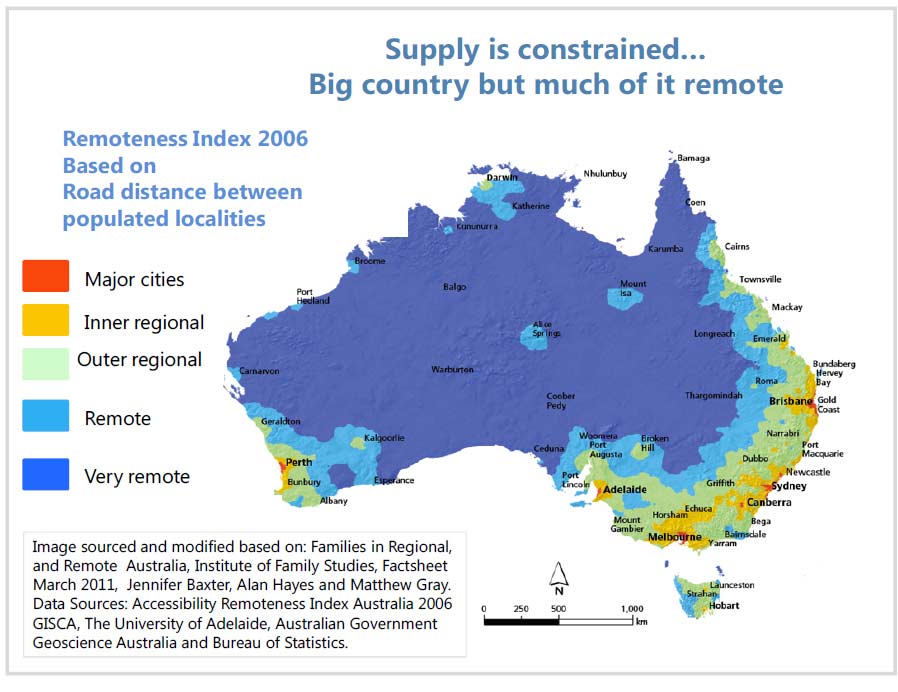

In emerging market and developing economies, policy priorities are varied given the diversity in conditions. Policymakers need to manage vulnerabilities and rebuild resilience against potential shocks while lifting growth and ensuring continued convergence toward advanced economy income levels. Net importers of commodities are facing reduced inflation pressures and external vulnerabilities, but in some, currency depreciations accompanying reduced capital inflows could limit the scope for monetary policy easing to support demand. In a number of commodity exporters, reducing public expenditures while raising their efficiency, strengthening fiscal institutions, and increasing noncommodity revenues would facilitate the adjustment to lower fiscal revenues. In general, allowing for exchange rate flexibility will be an important means for cushioning the impact of adverse external shocks in emerging market and developing economies, especially commodity exporters, though the effects of exchange rate depreciations on private and public sector balance sheets and on domestic inflation rates need to be closely monitored. Policymakers in emerging market and developing economies need to press on with structural reforms to alleviate infrastructure bottlenecks, facilitate a dynamic and innovation-friendly business environment, and bolster human capital. Deepening local capital markets, improving fiscal revenue mobilization, and diversifying exports away from commodities are also ongoing challenges in many of these economies.