The IMF released their Concluding Statement of the 2015 Article IV Mission today.

Australians have enjoyed exceptionally strong income growth for the last couple of decades. But the waning of the resource investment boom and the recent sharp fall in the terms of trade have brought this to a halt. Incomes should start rising again as the terms of trade stabilize, but likely more slowly than in the past. Improving this outlook requires policymakers being on the front foot to enable Australia to make the most of its considerable potential. This means supporting aggregate demand in the shorter term and boosting productivity in the longer term. And ensuring banks are unquestionably strong would reduce vulnerabilities. Such an ambitious reform agenda would require strong and sustained commitment.

Outperformance fading

Australia has grown almost twice as fast as its peers in the last two decades. This reflected both strong policy frameworks (such as the floating exchange rate and flexible labor market) and the boom in global demand for its resources. But output growth has been below trend for two years, unemployment has risen to six percent, and real incomes have declined. While moving from the investment to the production phase of the resource boom was always going to be bumpy and the economy is handling this transition relatively well, the recent sharp fall in resource prices has made it more difficult.

Weaker medium-term growth prospects

Over the next couple of years, activity should gradually pick up and narrow the output gap, supported by strong resource exports, accommodative monetary policy, and rising confidence. But over the medium term and without reform, growth is likely to converge to a slower potential rate, reflecting less capital accumulation and only modest productivity growth. This lower potential would still mean income growth in line with other advanced countries, but significantly slower than Australians have been used to over the last two decades. Slower growth would also make fiscal consolidation more difficult. The risks around this outlook seem somewhat skewed to the downside, in particular:

• On the downside, the envisaged pick up in non-resource business investment may remain elusive, a house price correction could knock confidence and demand, and China could slow more sharply.

• On the upside, domestic demand could respond more quickly to recent monetary policy stimulus, and the exchange rate could depreciate further, stimulating the tradable sector.

Policies to re-energize growth

This weaker outlook can be avoided. Australia has strong institutions, a flexible economy, and is well placed to seize opportunities created by Asia’s rapid growth and rising middle class, helped by the recent free trade agreements. Policymakers should build on these strengths by re-invigorating the reform agenda:

• Sustaining demand through the resource boom transition

• Lifting productivity to sustain strong income growth

• Building resilience to reduce the risk of financial disruption

Sustaining demand though the resource boom transition

Keeping monetary policy accommodative

A sizeable output gap, elevated unemployment, subdued inflation pressure, and an exchange rate still on the strong side, call for supportive aggregate demand policies. While monetary policy is already accommodative and may have lost some effectiveness, it should still stand ready to ease further should the recovery fall short of expectations and provided the financial stability risks remain contained.

Prudential policy to address housing risks

APRA has appropriately been taking targeted and gradual action to address areas of risk in the housing market for some time. Banks, however, seem only to have responded more recently and the results are yet to be fully reflected in the lending data. We expect APRA’s approach to succeed, but it may need to be intensified, for example, if investor lending and house price growth do not slow appreciably in the second half of the year. Such intensification could include requiring banks with fast-growing investor lending to hold more capital, raising risk weights on investor lending, and restricting the duration of interest-only loans.

Boosting public investment

A small surplus should remain a medium-term anchor of fiscal policy and budget discipline should be maintained. But the planned pace of consolidation nationally (Commonwealth and States combined) towards this medium-term objective is somewhat more frontloaded than desirable given the weakness of the economy, the size and uncertainty around the resource boom transition, and the possible limits to monetary policy. Increasing public investment (financed by more borrowing rather than offsetting measures) would support aggregate demand and ensure against downside risks. It would also employ resources released by the mining sector, catalyze private investment, boost productivity, take advantage of record-low borrowing rates, and maintain the government’s net worth. Indeed, IMF research suggests that economies like Australia—with an output gap, accommodative monetary policy, and fiscal space—benefit most from debt-financed infrastructure investment, with the growth boost largely containing the impact on the (low) debt-to-GDP ratio.

Commonwealth-State coordination critical

Boosting public investment, especially in the short term given inherent lags, and without waste and compromising governance, will be difficult, not least as most investment is carried out by States whereas the Commonwealth has the most borrowing capacity. The Commonwealth is already doing much to encourage investment with recent initiatives, including co-financing. However, public investment has been a drag on growth in recent quarters and the outlook is not for a sharp pick-up. A strategy for boosting public investment could include:

• Broadening the scope of investments supported by the Commonwealth, for example, to include a wider range of projects, including repairs and maintenance.

• Continuing to establish a pipeline of quality larger projects with transparent cost-benefit analysis, such as that being prepared by Infrastructure Australia. Broad political support for such a pipeline would reduce uncertainty and boost confidence.

• In addition to direct funding arrangements, the Commonwealth could consider guaranteeing States’ borrowing for additional investment—this would keep the accountability with the States, but reduce their concerns about credit ratings and would not affect the Commonwealth’s deficit.

Maintaining budget discipline

While the capital budget should expand, the recurrent budget should not. The government should maintain its envisaged structural consolidation of the recurrent budget. Any slippage would reduce the government’s net worth and could undermine the credibility of the medium-term surplus objective, which continues to serve the country well. Indeed, we see risks that the envisaged consolidation of the recurrent budget will not be achieved (given the tight spending targets, strong revenue projections, and with some measures still unapproved), which may well require additional measures.

Lifting productivity to sustain strong income growth

No silver bullet, but many targets

Maintaining income growth at past rates requires raising total factor productivity growth substantially. This will be challenging as Australia has already undertaken comprehensive productivity-boosting reforms in the 1980-early 2000s and a number of sectors are at, or near, the global productivity frontier. But other sectors have gaps, and these provide an opportunity to catch up—the distribution (including retail, wholesale, and transport) sector suggests most scope. The Competition Policy Review recommended many reforms to strengthen competition and improve efficiency, including in human services and the retail sectors. Filling infrastructure gaps would relieve bottlenecks, as would reducing the long-standing constraints on housing supply (which, critically, requires more responsive planning and zoning). More generally, the Productivity Commission has identified a wide-ranging list of reforms and is a world-class resource that could help guide this policy agenda.

Tax reform—a key policy lever

Though politically challenging, a comprehensive tax reform could both increase growth and generate revenue over time to help return the budget to surplus. A comprehensive and decisive package would be needed to deliver tangible results. The on-going Tax and Federation reviews provide the opportunity to craft such a package, which should include the following inter-connected elements:

• Shifting towards more efficient and simple taxes. In particular: by preventing a large share of individual taxpayers from facing higher tax rates through unchecked bracket creep (which would affect those on lower and middle incomes most), reducing the corporate tax rate to international levels, and eliminating stamp duties and minor taxes. This would be paid for by broadening the base of the GST and possibly raising the rate—while at least fully compensating those on lower incomes—and relying more on a broad-based real-estate tax and excises.

• Ensuring fairness. A number of measures, such as reducing the concessional treatment of superannuation contributions and earnings for those on higher incomes, and the discount on capital gains, would be important for fairness. They would also enhance revenue and could improve housing affordability and financial stability. Adjusting any of these policies would need careful calibration and phasing, and should be introduced in tandem with the measures to enhance efficiency.

• Adjusting federal fiscal relations. Federal-State relations will likely need to be adjusted to facilitate the tax reform. There are many options—one could be for States to receive higher GST revenue and autonomy in return for greater spending responsibilities. This could also help increase spending efficiency.

Building resilience to reduce the risk of financial disruption

Ensuring unquestionably strong banks

Banks are highly rated and profitable, non-performing loans and funding costs are low, and wholesale funding reliance has declined and its maturity lengthened substantially since the global financial crisis. Nonetheless, the system is dominated by four large banks with similar business models which rely significantly on wholesale external borrowing, most lending is housing related, and household debt and house prices are elevated. And although capital ratios have risen since the global financial crisis, this largely reflects a shift towards mortgages and a lowering of risk weights. Implementing the recommendations of the Financial System Inquiry should be a priority.

Raising capital

While international comparisons are fraught with difficulty, Australian banks do not appear to have particularly high capital ratios and the global trend is upwards. More tangibly, the recent APRA stress test indicates that in a severe adverse scenario, bank capital would have to be substantially higher to ensure a fully-functioning system. Putting a floor of 25-30 percent on mortgage risk weights would help, but capital ratios would also need to rise substantially. Given major banks’ high profitability, such ratios can be achieved at little, if any, macroeconomic cost, especially if done gradually, and will make the financial system, the budget, and the economy stronger.

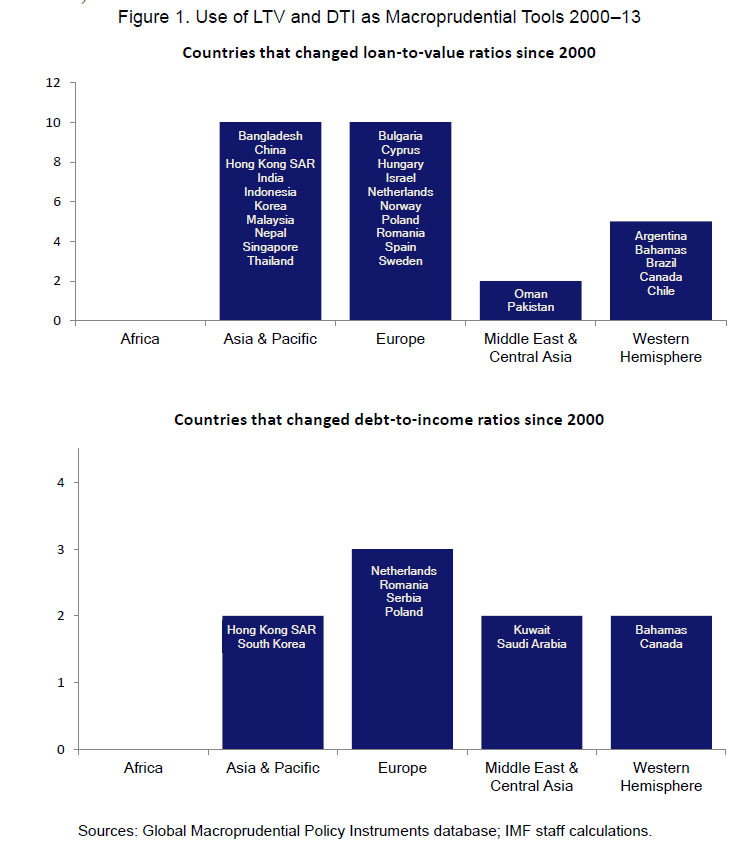

In most cases,the caps on LTV and DTI started in the range of 60–85 percent and 30–45 percent, respectively, for mortgage loans. In all countries, there were changes to the limits of LTV/DTIs typically because the authorities noted that they were not having the desired effect. In some cases, house price and mortgage growth did not fall, and in other cases, the limits did not bind. Concerned with speculative activities, authorities in some countries lowered the caps selectively either for speculative prone (geographical) areas or for individuals with multiple mortgages. In one case, the centrally set caps were removed and banks were allowed to set their own limits, validated by supervisors. However, this did not work, and stricter requirements were put back in place.

In most cases,the caps on LTV and DTI started in the range of 60–85 percent and 30–45 percent, respectively, for mortgage loans. In all countries, there were changes to the limits of LTV/DTIs typically because the authorities noted that they were not having the desired effect. In some cases, house price and mortgage growth did not fall, and in other cases, the limits did not bind. Concerned with speculative activities, authorities in some countries lowered the caps selectively either for speculative prone (geographical) areas or for individuals with multiple mortgages. In one case, the centrally set caps were removed and banks were allowed to set their own limits, validated by supervisors. However, this did not work, and stricter requirements were put back in place.