Over the past year, Australia’s recovery under the transition from the mining boom has continued despite setbacks. Domestic demand growth has strengthened, and employment growth has picked up markedly since the beginning of the year, most of it in full-time jobs. But labor market slack remains present, and wage growth has remained weak. Beyond wages, stronger retail competition and continued declines in import prices have contributed to inflation outcomes below the mid-point of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s target range of 2 to 3 percent. With stronger terms of trade, the current account deficit has narrowed substantially and the trade balance has moved into surplus, primarily because of higher global prices for coal and iron ore.

Looking forward, conditions are in place for a pick-up in economic growth to above-trend rates. The improved picture reflects a stronger global outlook, recent stronger employment growth, and a stronger contribution from infrastructure investment with positive spillovers to private investment and the rest of the economy, more than offsetting the declining contribution from dwelling investment. Non-mining private business investment should rebound further, while the drag from mining investment should be ending.

The pickup in growth is likely to be modest, while inflation and wages will be slow to rise. Household consumption is expected to be held back by low real wage growth, given labor market slack and structural change in some sectors. Economic slack is projected to decline gradually. Upward pressure on prices and wages should emerge once the economy has been at full employment, including lower underemployment, for some time.

With stronger momentum in domestic demand and inflation close to the midpoint of the target range not yet secured, continued macroeconomic policy support will remain essential . With a welcome pickup in public investment, the overall fiscal stance is expected to be broadly neutral in 2017 and 2018. With the cash rate at 1.5 percent, monetary policy remains appropriately accommodative. With Australia’s recovery lagging that of other major advanced economies, monetary policy should remain firmly focused on ensuring stronger sustained momentum in domestic demand and inflation.

The Commonwealth government’s budget repair strategy is appropriately anchored by medium-term budget balance targets . The strategy is predicated on a rapid rebound of nominal growth to trend, leading to structural revenue and expenditure improvements. The risk is that with a gradual recovery, the rebound to trend might not be as quick as expected. Australia has the fiscal space to absorb this risk and protect or, if needed, increase the spending envelopes for infrastructure investment, structural reforms supporting trend growth and productivity.

Near-term risks to growth have become more balanced, but large external shocks, including their interaction with the domestic housing market, are an important downside risk. On the positive side, the improved global outlook could lead to a stronger-than-expected recovery, underpinned by a larger pickup in non-mining business investment. On the downside, there is the risk of unexpectedly tighter global financial conditions flowing through to domestic financial conditions in Australia while the economy is still recovering. Australia is also particularly exposed to downside risk from China through its trade links in commodities and services. Domestically, growth in consumer spending could weaken if improvements in household incomes turn out to be more gradual than expected, or if a cooling housing market and high debt to income ratios discourage further declines in household saving rates.

Managing Housing Imbalances and Financial Sector Risks

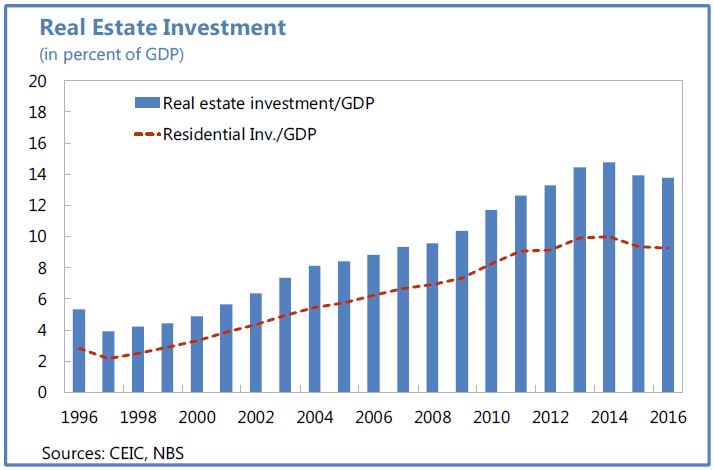

The housing market is expected to cool, but imbalances—lower housing affordability and household debt vulnerabilities—are unlikely to be corrected soon. In the absence of a major shock to the economy, the cooling is expected to be driven mainly by the building completion rate catching up with demand in the major eastern capital regions. But given continued strong population growth and foreign buyer interest, demand growth for housing is expected to remain robust, and, in the absence of a large inventory of vacant properties, prices should stabilize, rather than fall significantly. Declines in household debt-to-income ratios would thus need to be driven by strong nominal income growth and amortization.

The Commonwealth and States have appropriately used a multi-pronged approach to address increasing housing market imbalances and related systemic risks to banks.

Prudential policies by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) have lowered the risks to the banking sector from their large exposure to the housing market in a low-interest rate environment, primarily through a sequential tightening of required underwriting standards. The latest round involved tighter standards on the origination of interest-only loans, and reinforced a cap on lending growth to investors. On the demand side, some States have helped qualified first-time homebuyers to enter the market, including through grants and exemption from stamp duty. In addition, the Commonwealth is assisting those buyers to build savings more quickly for a home deposit via the superannuation system.

Supply-side policies will be most effective in achieving housing affordability in the longer term. The housing supply response is being strengthened through a variety of measures at the State and Commonwealth levels, increasing the supply of developable land and the efficiency of its use. including higher housing densification. These include ramping up infrastructure spending and reforms to planning and zoning. These steps have appropriately been complemented by measures to provide for increases in the supply of affordable housing targeted to lower- and middle-income households.

Supply-side policies could also help in raising productivity and trend growth. Ensuring longer-term affordability in housing, and location cost more broadly, could lower risks that businesses and people are not able to move to the urban areas where they would be most productive because of agglomeration and other network externalities. This, in turn, would also help lower risks to longer-term growth.

These policy efforts should be complemented by tax reform . Housing-related tax settings can also play a role in strengthening supply and efficient use of land and, in the longer term, should limit potential distortions they might introduce in the demand for property. The State stamp duty tax regimes are inefficient—they have narrow tax bases, and discourage mobility and transactions in existing properties that could have more productive alternative uses. It should be replaced with a systematic land tax regime applying to all residential and commercial properties. As demonstrated by the recent reform in the Australian Capital Territory, the transition can be gradual, which helps to avoid a disruptive impact on State revenues. Cash flow problems for low-income homeowners can be addressed through deferment options.

Prudential reform efforts on lifting banks’ mortgage asset quality are appropriately complemented by reforms refining the capital adequacy framework. In combination with higher capital adequacy and liquidity requirements, tighter mortgage underwriting standards have strengthened banks’ resilience to housing market shocks. APRA is in the process of further refining the capital adequacy framework. In July 2017, it clarified the capital requirements for Australian banks’ to “be unquestionably strong,” as suggested by the 2014 Financial Sector Inquiry. It is also preparing regulations to address the systemic risk from banks’ concentrated exposure to residential mortgages through capital requirements.

Fostering Long-Term Growth Opportunities

Reforms could lift productivity growth . The decline in trend output growth in Australia over the past decade or so was driven mainly by lower labor force growth and lower rates of capital accumulation, both developments reflecting corrections after the mining investment boom which are likely to have run their course. Average productivity growth has picked up recently, primarily because of the transition to higher capital stock utilization in the mining sector. Nevertheless, productivity growth could be lifted by reforms.

There is scope to expand infrastructure spending beyond the recent increase in the fiscal envelope. According to some international metrics, Australia has a notable infrastructure gap compared with many other advanced economies. While the recent boost has helped to narrow the gap, it might not be enough to close it. Further increases in investment have the potential to improve physical and digital interconnectivity, both internally and with Australia’s trading partners, thereby contributing to higher growth.

Fostering innovation, research and workforce skills upgrades, would complement the productivity effects from more infrastructure.

- Australia’s research and development (R&D) share of GDP lags other OECD members. But the relatively small scale National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA) is only funded through FY2018/19. A clear implementation of the upcoming 2030 Strategic Plan for the Australian Innovation, Science and Research System by defining the scope and funding of policy instruments would help strengthen the reach and magnitude from its possible positive productivity externalities.

- Flexible labor markets have contributed to relatively smooth adjustment after the end of the mining boom. But with continued structural change and higher under- or unemployment in some age and skill cohorts, defining a longer-term envelope for active labor market policies for workforce re-education and skill upgrades can help raise human capital and labor force participation, such as the levy proposed to maintain the new Skilling Australians Fund.

Productivity and inclusion could also be supported with a broad tax reform package . The Commonwealth government has implemented a reform by lowering the corporate income tax rate for SMEs, with the goal of broadening it to all firms at an even lower rate. A more comprehensive tax reform has the potential to increase efficiency of the tax system, increase investment and labor demand, and reduce inequality. This would entail lowering taxes on income from mobile factors of production (capital and labor) and increasing reliance on taxes on immobile factors of production (land) and indirect taxes on consumption, undertaken in a revenue neutral way. Such a reform would complement the switch to a broad-based tax on land instead of stamp duties already discussed.

Reconsidering broad tax reforms. Concerns about the regressive nature of higher taxes on consumption at a time of low wage growth could be addressed by broadening the base, reducing generous tax concessions (some of which are not means-tested or are limited), and revising the design of the income tax reform. Two developments could encourage reconsideration of tax reform. First, significant corporate income tax reductions in other large advanced economies, which would have capital flow implications of potential concern for Australia. Second, the ongoing Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation Review by the Productivity Commission is reopening consideration of the distribution of GST revenues, which could allow for a broader package for agreement between the Commonwealth and the States.

The proposed areas of reform suggested above could draw further measures from the recent work by the Productivity Commission. In its inaugural 5-Year Productivity Review, the Commission has proposed structural reforms in health, education, urban development, and regulatory aspects of market efficiency. These proposals could define new policy parameters, which could also increase certainty about policy directions for business investment decisions. These would also build upon the recently enacted legislative agenda of the Competition Policy Review (the Harper report) at the Commonwealth level. At the State level, there are still further agreements needed to fulfill the Harper report’s implementation.

A Concluding Statement describes the preliminary findings of IMF staff at the end of an official staff visit (or ‘mission’), in most cases to a member country. Missions are undertaken as part of regular (usually annual) consultations under Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, in the context of a request to use IMF resources (borrow from the IMF), as part of discussions of staff monitored programs, or as part of other staff monitoring of economic developments.

The authorities have consented to the publication of this statement. The views expressed in this statement are those of the IMF staff and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF’s Executive Board. Based on the preliminary findings of this mission, staff will prepare a report that, subject to management approval, will be presented to the IMF Executive Board for discussion and decision.