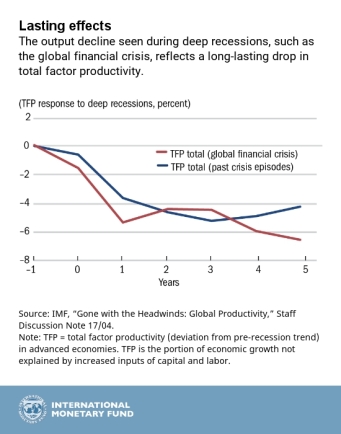

The 2008 global financial crisis was exceptionally severe in the magnitude, breadth, and persistence of its effects, but it is one in a long series of financial crises stretching back centuries. Not only do crises cause financial losses for professional investors; more importantly, they impose high human costs for those who lose their jobs, homes, and savings. To protect their citizens, governments generally adopt an array of financial regulations designed to reduce the risk of a failure that could reverberate across the economy. These include balance-sheet standards, insider trading rules, broader conflict-of-interest laws, and consumer protections.

Too far?

Some argue that such existing regulations go too far and mostly hurt the economy by reducing financial institutions’ profits and thereby their ability to provide essential services. They claim that banks and other financial institutions—acting in their shareholders’ interest—would not knowingly risk failure; even if they avoid insolvency, the damage to their reputations would put them out of business. Yet history abounds with examples of reckless behavior, ranging from the Dutch Tulip Mania of the seventeenth century to the subprime lending boom of the 2000s. And even when a financial firm’s managers soberly assess their own personal risks, they still may not be prudent enough from society’s perspective, because some costs of failure fall on others, such as their shareholders and the taxpayers who must ultimately pay if there is a government bailout.

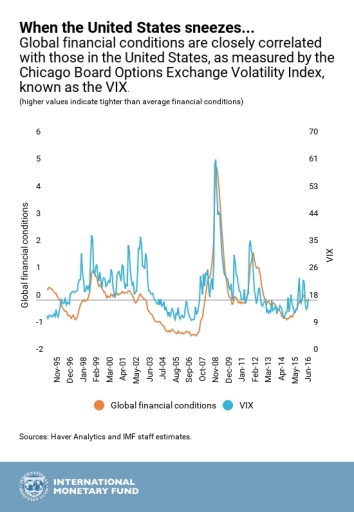

But the task of financial-sector oversight, never easy, has become more complex over the past 50 years as financial activity increasingly crosses national boundaries. That is why national governments have stepped up collaboration to promote stability and create a level playing field in international financial markets.

The global scope of modern finance creates at least four major complications for national regulators and supervisors. First, it is hard to assess the operations of financial institutions that extend beyond their home countries. Second, financial firms may take advantage of regulatory differences among countries to place their riskiest activities in lightly-regulated locations. Third, complex institutions with operations spanning several national jurisdictions are harder to wind down if they fail. And fourth, countries might actively compete for international financial business while also supporting their national “champions” through lax regulatory standards. All of these factors undermine the stability of the global financial system, especially as financial instruments and networks become more complex.

Forums for international cooperation

To address these challenges, national regulators launched in 1974 a process of consultation and coordination under the aegis of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. The Basel Committee focuses on banking regulation, whereas the Financial Stability Board, set up by the G20 after the financial crisis of 2008, coordinates the development of regulatory policies across the broader international financial markets, bringing together national authorities, international financial institutions, and sectoral standards setters.

Governments cooperate through the Basel Committee and the Financial Stability Board because no single national authority, acting by itself, can guarantee the stability of its own financial system when banks and other financial institutions operate globally. International agreements on regulatory and supervisory standards discourage a race to the bottom by establishing a level global playing field for financial industry competition. More generally, when countries compete for business through excessive deregulation, all end up worse off because financial accidents become more likely, and, when they happen, are more severe and more likely to propagate across borders.

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, the Basel Committee undertook a major initiative, known as the Basel III accord, which includes higher minimum standards for both the quality and quantity of bank capital (the equity cushion that allows banks to absorb losses without going bankrupt and needing government support). While sufficient bank capital is vital, even higher capital levels could be threatened in a severe panic, so the accord includes additional measures to reduce banking risk. As a result, even though Basel III is still being phased in globally, banks are already much better capitalized and less vulnerable to market jitters than they were a decade ago.

The United States, which made banks recapitalize and restructure more aggressively after the crisis, recovered more quickly than countries that did not. But a safe global financial system needs more than balance-sheet constraints for banks. In parallel with the development of the Basel III standards, the Financial Stability Board created a common approach to handling the failure of the largest and most systemic financial institutions. It is critical that insolvent institutions can be wound down safely, even when they are big, international, complex, or otherwise would pose a threat to the broader financial system in case of failure. If they cannot, government bailouts are more likely, risk-taking is excessive, and market discipline is subverted.

Of course, financial regulation involves tradeoffs. In principle, requiring more capital and liquidity can raise the cost of credit for households and businesses or reduce market liquidity. So far, research studies indicate that any unintended consequences are relatively small. Yet the benefits of a safer financial system are unquestionably large.

Although the financial system is safer today, it is also true that financial regulations have become much more complex. In the United States, for example, the Dodd-Frank Act is more than a thousand pages long and has generated tens of thousands of pages of follow-up implementation rules. There is certainly room for simplification. For example, the threshold for designating banks as systemic and hence subject to enhanced regulatory standards, currently set at a balance-sheet size of $50 billion, might be made more flexible. Regulation of community banks could also be simplified without making the system riskier, as could the implementation of stress tests, which aim to assess banks’ resilience to potential economic and financial shocks.

At the same time, the core tenets of the new global regulatory regime must be preserved. Paradoxically, the relative resilience of financial markets in recent years, which is partly the result of more stringent internationally agreed standards, has itself been cited to argue that financial regulation is an excessive drag on growth. This view is shortsighted. As Hyman Minsky, a well-known writer on financial crises, put it, “success breeds a disregard of the possibility of failure…” In other words, policymakers should not be lulled into forgetting the hard lessons of the not-so-distant past. Continuing international financial cooperation remains essential—it is the solid foundation of a strong and stable world economy.