Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer spoke at the “Macroprudential Monetary Policy” conference. He remains concerned that the U.S. macroprudential toolkit is not large and is not yet battle tested. The contention that macroprudential measures would be a better approach to managing asset price bubbles than monetary policy, he says, is persuasive, except when there are no relevant macroprudential measures available. It also seems likely that monetary policy should be used for macroprudential purposes with an eye to the tradeoffs between reduced financial imbalances, price stability, and maximum employment.

This afternoon I would like to discuss the challenges to formulating macroprudential policy for the U.S. financial system.

The U.S. financial system is extremely complex. We have one of the largest nonbank sectors as a percentage of the overall financial system among advanced market economies. Since the crisis, changes in the regulation and supervision of the financial sector, most significantly those related to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act) and the Basel III process, have addressed many of the weaknesses revealed by the crisis. Nonetheless, challenges to our efforts to preserve financial stability remain.

The Structure, Vulnerabilities, and Regulation of the U.S. Financial System

To set the stage, it is useful to start with a brief overview of the structure of the U.S. financial system. A diverse set of institutions provides credit to households and businesses, and others provide deposit-like services and facilitate transactions across the financial system. As can be seen from panel A of figure 1, banks currently supply about one-third of the credit in the U.S. system. In addition to banks, institutions thought of as long-term investors, such as insurance companies, pension funds, and mutual funds, provide anotherone-third of credit within the system, while the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), primarily Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, supply 20 percent of credit. A final group, which I will refer to as other nonbanks and is often associated with substantial reliance on short-term wholesale funding, consists of broker-dealers, money market mutual funds (MMFs), finance companies, issuers of asset-backed securities, and mortgage real estate investment trusts, which together provide 14 percent of credit.

In the first quarter of this year, U.S. financial firms held credit market debt equal to $38 trillion, or 2.2 times the gross domestic product (GDP) of the United States. As the figure shows, the size of the financial sector relative to GDP grew for nearly 50 years but declined after the financial crisis and has only started increasing again this year.

From the perspective of financial stability, there are two important dimensions along which the categories of institutions in figure 1 differ. First, banks, the GSEs, and most of what I have called other nonbanks tend to be more leveraged than other institutions. Second, some institutions are more reliant on short-term funding and hence vulnerable to runs. For example, MMFs were pressured during the recent crisis, as their deposit-like liabilities–held as assets by highly risk-averse investors and not backstopped by a deposit insurance system–led to a run dynamic after a large fund broke the buck. In addition, nearly half of the liabilities of broker-dealers consists–and consisted then–of short-term wholesale funding, which proved to be unstable in the crisis.

The pros and cons of a multifaceted financial system

The significant role of nonbanks in the U.S. financial system and the associated complex web of interconnections bring both advantages and challenges relative to the more bank-dependent systems of other advanced economies. A potential advantage of lower bank dependence is the possibility that a contraction in credit supply from banks can be offset by credit supply from other institutions or capital markets, thereby acting as a spare tire for credit supply. Historical evidence suggests that the credit provided by what I termed long-term investors–that is, insurance companies, pension funds, and mutual funds–has tended to offset movements in bank credit relative to GDP, as indicated by the strong negative correlation of credit held by these institutions with bank credit during recessions. In other words, these institutions have acted as a spare tire for the banking sector.However, complexity also poses challenges. While the financial crisis arguably started in the nonbank sector, it quickly spread to the banking sector because of interconnections that were hard for regulators to detect and greatly underappreciated by investors and risk managers in the private sector.6 For example, when banks provide loans directly to households and businesses, the chain of intermediation is short and simple; in the nonbank sector, intermediation chains are long and often involve a multitude of both banks and other nonbank financial institutions.

Regulatory, supervisory, and financial industry reforms since the crisis

U.S. regulators have undertaken a number of reforms to address weaknesses revealed by the crisis. The most significant set of reforms has focused on the banking sector and, in particular, on regulation and supervision of the largest, most interconnected firms. Changes include significantly higher capital requirements, additional capital charges for global systemically important banks, macro-based stress testing, and requirements that improve the resilience of banks’ liquidity risk profile.Changes for the nonbank sector have been more limited, but steps have been taken, including the final rule on risk retention in securitization, issued jointly by the Federal Reserve and five other agencies in October of last year, and the new MMF rules issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in July of last year, following a Section 120 recommendation by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). More recently, the SEC has also proposed rules to modernize data reporting by investment companies and advisers, as well as to enhance liquidity risk management and disclosure by open-end mutual funds, including exchange-traded funds. Other provisions include the central clearing requirement for standardized over-the-counter derivatives and the designation by the FSOC of four nonbanks as systemically important financial institutions. The industry has also undertaken important changes to bolster the resilience of its practices, including notable improvements to internal risk-management processes.

Some challenges to macroprudential policy

The steps taken since the crisis have almost certainly improved the resilience of the U.S. financial system, but I would like to highlight two significant challenges that remain.First, new regulations may lead to shifts in the institutional location of particular financial activities, which can potentially offset the expected effects of the regulatory reforms. The most significant changes in regulation have focused on large banks. This focus has been appropriate, as large banks are the most interconnected and complex institutions. Nonetheless, potential shifts of activity away from more regulated to less regulated institutions could lead to new risks.

It is still too early to gauge the degree to which such adaptations to regulatory changes may occur, although there are tentative signs. For example, we have seen notable growth in mortgage originations at independent mortgage companies as reflected in the striking increase in the share of home-purchase originations by independent mortgage companies from 35 percent in 2010 to 47 percent in 2014. This growth coincides with the timing of Basel III, stress testing, and banks’ renewed appreciation of the legal risks in mortgage originations. As another example, there have also been many reports of diminished liquidity in fixed-income markets. Some observers have linked this shift to new regulations that have raised the costs of market making, although the evidence for changes in market liquidity is far from conclusive and a range of factors related to market structure may have contributed to the reporting of such shifts.

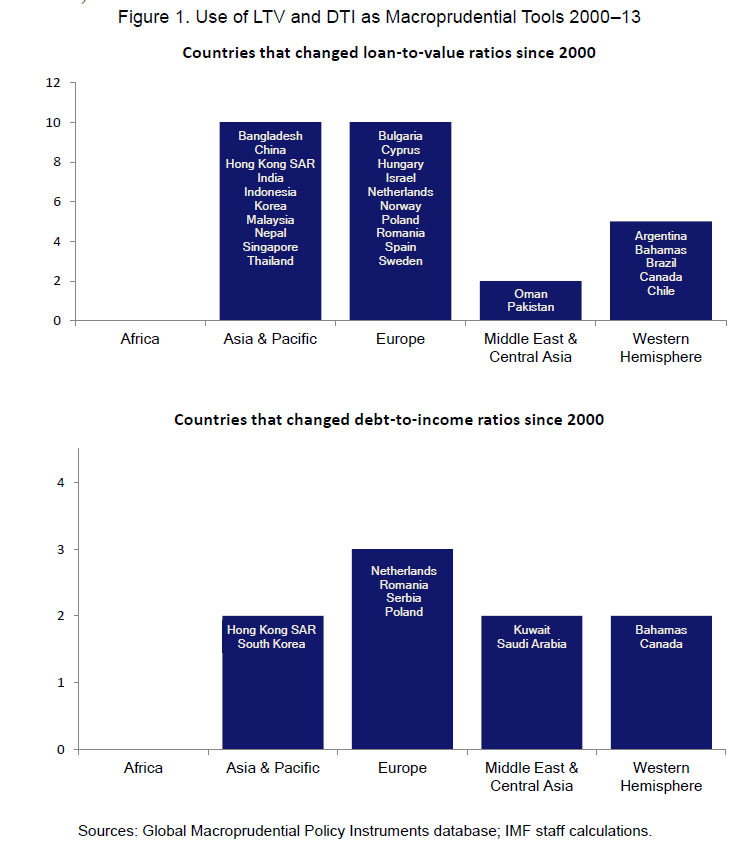

Despite limited evidence to date, the possibility of activity relocating in response to regulation is a potential impediment to the effectiveness of macroprudential policy. This is clearly the case when activity moves from a regulated to an unregulated institution. But it may also be relevant even when activity moves from one regulated institution to an institution regulated by a different authority. This scenario can occur in the United States because different regulators are responsible for different institutions, and financial stability traditionally has not been, and in a number of cases is still not, a central component of these regulators’ mandates. To be sure, the situation has improved since the crisis, as the FSOC facilitates interagency dialogue and has a shared responsibility for identifying risks and reporting on these findings and actions taken in its annual report submitted to the Congress. In addition, FSOC members jointly identify systemically important nonbank financial institutions. Despite these improvements, it remains possible that the FSOC members’ different mandates, some of which do not include macroprudential regulation, may hinder coordination. By contrast, in the United Kingdom, fewer member agencies are represented on the Financial Policy Committee at the Bank of England, and each agency has an explicit macroprudential mandate. The committee has a number of tools to carry out this mandate, which currently are sectoral capital requirements, the countercyclical capital buffer, and limits on loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios for mortgage lending.

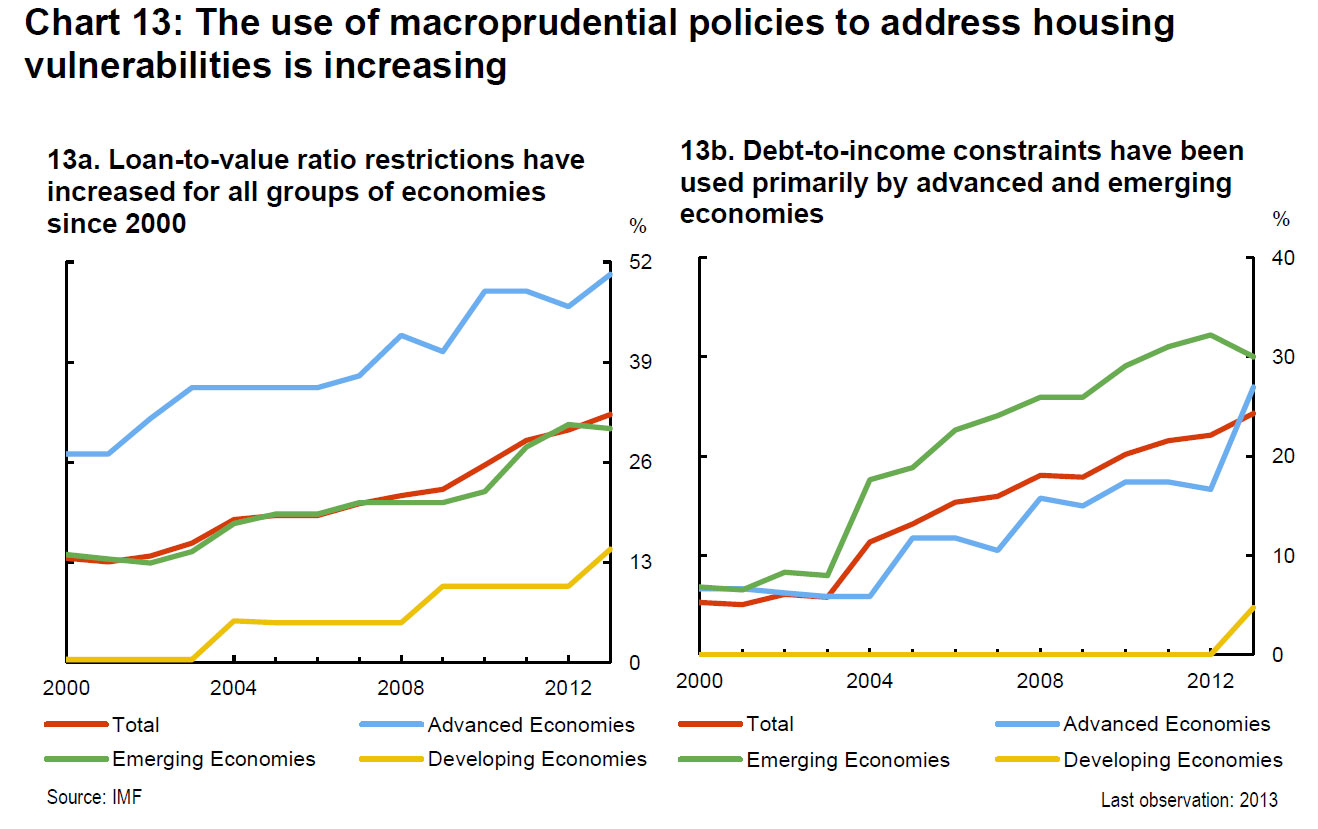

A second significant challenge to macroprudential policy remains the relative lack of measures in the U.S. macroeconomic toolkit to address a cyclical buildup of financial stability risks. Since the crisis, frameworks have been or are currently being developed to deploy some countercyclical tools during periods when risks escalate, including the analysis of salient risks in annual stress tests for banks, the Basel III countercyclical capital buffer, and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) proposal for minimum margins on securities financing transactions. But the FSB proposal is far from being implemented, and a number of tools used in other countries are either not available to U.S. regulators or very far from being implemented. For example, several other countries have used tools such as time-varying risk weights and time-varying loan-to-value and debt-to-income caps on mortgages. Indeed, international experience points to the usefulness of these tools, whereas the efficacy of new tools in the United States, such as the countercyclical capital buffer, remains untested.

In considering the difficulties caused by the relative unavailability of macroprudential tools in the United States, we need to recognize that there may well be an interaction between the extent to which the entire financial system can be strengthened and made more robust through structural measures–such as those imposed on the banking system since the Dodd-Frank Act–and the extent to which a country needs to rely more on macroprudential measures. Inter alia, this recognition could provide an ex post rationalization for the United States having imposed stronger capital and other charges than most foreign countries.

Implications for monetary policy

Though I remain concerned that the U.S. macroprudential toolkit is not large and not yet battle tested, that does not imply that I see acute risks to financial stability in the near term. Indeed, banks are well capitalized and have sizable liquidity buffers, the housing market is not overheated, and borrowing by households and businesses has only begun to pick up after years of decline or very slow growth. Further, I believe that the careful monitoring of the financial system now carried out by Fed staff members, particularly those in the Office of Financial Stability Policy and Research, and by the FSOC contributes to the stability of the U.S. financial system–though we have always to remind ourselves that, historically, not even the best intelligence services have succeeded in identifying every significant potential threat accurately and in a timely manner. This is another reminder of the importance of building resilience in the financial system.Nonetheless, the limited macroprudential toolkit in the United States leads me to conclude that there may be times when adjustments in monetary policy should be discussed as a means to curb risks to financial stability. The deployment of monetary policy comes with significant costs. A more restrictive monetary policy would, all else being equal, lead to deviations from price stability and full employment. Moreover, financial stability considerations can sometimes point to the need for accommodative monetary policy. For example, the accommodative U.S. monetary policy since 2008 has helped repair the balance sheets of households, nonfinancial firms, and the financial sector.

Given these considerations, how should monetary policy be deployed to foster financial stability? This topic is a matter for further research, some of which will look similar to the analysis in an earlier time of whether and how monetary policy should react to rapidly rising asset prices. That discussion reached the conclusion that monetary policy should be deployed to deal with errant asset prices (assuming, of course, that they could be identified) only to the extent that not doing so would result in a worse outcome for current and future output and inflation.

There are some calculations–for example, by Lars Svensson–that suggest it would hardly ever make sense to deploy monetary policy to deal with potential financial instability. The contention that macroprudential measures would be a better approach is persuasive, except when there are no relevant macroprudential measures available. I believe we need more research into the question. I also struggle in trying to find consistency between the certainty that many have that higher interest rates would have prevented the Global Financial Crisis and the view that the interest rate should not be used to deal with potential financial instabilities. Perhaps that problem can be solved by seeking to distinguish between a situation in which the interest rate is not at its short-run natural rate and one in which asset-pricing problems are sector specific.

Of course, we should not exaggerate. It is one thing to say we have no macroprudential tools and another to say that having more macroprudential measures–particularly in the area of housing finance–could provide major financial stability benefits. It also seems likely that monetary policy should be used for macroprudential purposes with an eye to the tradeoffs between reduced financial imbalances, price stability, and maximum employment. In this regard, a number of recent research papers have begun to frame the issue in terms of such tradeoffs, although this is a new area that deserves further research.

It may also be fruitful for researchers to continue investigating the deployment of new or little-used monetary policy tools. For example, it is arguable that reserve requirements–a traditional monetary policy instrument–can be viewed as a macroprudential tool. In addition, some research has begun to ask important questions about the size and structure of monetary authority liabilities in fostering financial stability.

Conclusion

To sum up: The need for coordination across different regulators with distinct mandates creates challenges to the timely deployment of macroprudential measures in the United States. Further, the toolkit to act countercyclically in the face of building financial stability risks is limited, requires more research on its efficacy, and may need to be enhanced. Given these challenges, we need to consider the potential role of monetary policy in fostering financial stability while recognizing that there is more research to be done in clarifying the potential costs and benefits of doing so when conditions appear so to warrant.After all of the successful work that has been done to reform the financial system since the Global Financial Crisis, this summary may appear daunting and disappointing. But it is important to highlight these challenges now. Currently, the U.S. financial system appears resilient, reflecting the impressive progress made since the crisis. We need to address these questions now, before new risks emerge.