Andrew Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, gave the annual Maxwell Fry lecture on Global Finance at Birmingham University. There are some powerful observations here, relevant to the Australian context, as well as the potential to amplify risks associated with a more interconnected world. He also takes macroprudential discussions further.

Andrew’s main theme was the growing size and complexity of global capital flows between countries. He noted that ‘cross-border stocks of capital are almost certainly larger than at any time in human history’. And the apparent independence of domestic investment from domestic saving suggests that ‘measured levels of global capital market integration … remain at higher levels than at any point in history’. He discussed how this can be ‘double-edged’ from a financial stability perspective: it both shares risk (which can be stabilising) but also spreads and amplifies risk (which can be destabilising) – potentially generating ‘more frequent and/or larger dislocations’.

He argued that many lessons have been learned from the financial crisis, not least the need to ‘safeguard against systemic risk’. Yet when it comes to the fortunes of the international monetary system ‘it is far from clear that these lessons have been learned, much less that the international rules of the road have been reformed’. ‘Arguably, the rules of the road for this system have failed to keep pace with the growing scale and complexity of global financial flows’.

One of the consequences of the growth in cross border capital flows is ‘the steady rise in the degree of co-movement in asset prices over time’. Cross-border spillovers are becoming more important and global common factors more potent. A particular example is the behaviour of yield curves across countries. ‘To a first approximation, global yield curves appear these days to be dancing to a common tune’.

Andrew identified four areas where the global financial system could be strengthened:

a) Improve global financial surveillance, by tilting IMF surveillance away from monitoring individual country risk and towards multilateral surveillance and having more real-time tracking of the global flow of funds.

b) Improve country debt structures, for example by encouraging countries to issue GDP linked bonds, or Contingent Convertible (CoCo) bonds.

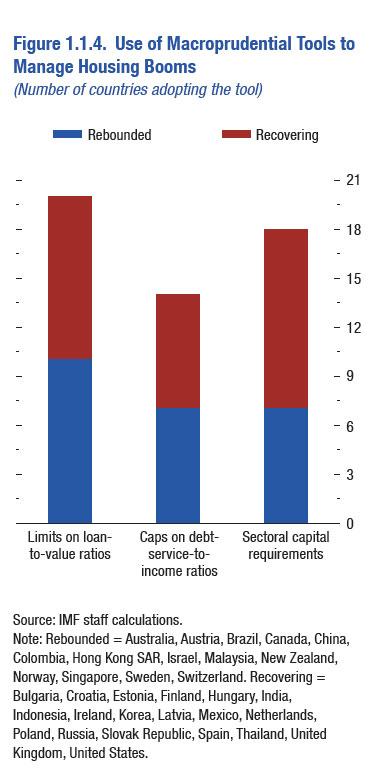

c) Enhance macro-prudential and capital flow management policies. For example, he suggests that ‘total credit follows a global cycle that has strengthened over time’ in which case ‘there may in future be a case for national macro-prudential policies leaning explicitly against these global factors’ taking international macro-prudential policy co-ordination ‘to the next level’. This next phase of macro-prudential policy may see measures ‘targeted at particular markets, as well as particular countries’.

d) Improve international liquidity assistance, for example by increasing the resources available to the IMF.

However, looking at TAS, we see some interesting variations. There the LTI’s are higher, reflecting lower incomes relative to somewhat lower house prices. We have adjusted the sample to take account of the smaller populations.

However, looking at TAS, we see some interesting variations. There the LTI’s are higher, reflecting lower incomes relative to somewhat lower house prices. We have adjusted the sample to take account of the smaller populations.

QLD shows greater concentration at lower LTI’s but then a second smaller peak at the upper end.

QLD shows greater concentration at lower LTI’s but then a second smaller peak at the upper end. SA has quite a spike around 4.5 times, and a second peak around 6.5, again reflecting lower income levels in that state.

SA has quite a spike around 4.5 times, and a second peak around 6.5, again reflecting lower income levels in that state. If we then start to look at segments, we find that affluent group, Exclusive Professionals, has a consistently lower LTI, compared with…

If we then start to look at segments, we find that affluent group, Exclusive Professionals, has a consistently lower LTI, compared with…