Our love affair with property has pushed Australia’s residential housing market to an eye-watering value of $6.2 trillion.

But as we scramble over each other to snap up property while interest rates are at historic lows, we have gotten ourselves into a bit of a pickle. We might not actually be able to afford funding our affair.

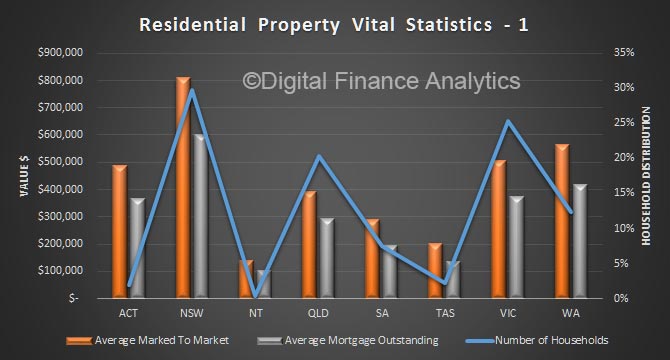

An analysis, based on extensive surveys of 26,000 Australian households, compiled by Digital Finance Analytics, examined how much headroom households have to rising rates, taking account of their income, size of mortgage, whether they have paid ahead, and other financial commitments. And the results are distressing.

It showed that around 20 per cent — that’s one in five homeowners — would find themselves in mortgage difficulty if interest rates rose by 0.5 per cent or less. An additional 4 per cent would be troubled by a rise between 0.5 per cent and one per cent.

Almost half of homeowners (42 per cent) would find themselves under financial pressure if home loan interest rates were to increase from their average of 4.5 per cent today to the long term average of 7 per cent.

“This is important because we now expect mortgage rates to rise over the next few months, as higher funding costs and competitive dynamics come into pay, and as regulators bear down on lending standards,” Digital Finance Analytics wrote.

The major banks have already started increasing their home loan rates this year, despite the market broadly expecting the Reserve Bank to keep the cash rate steady at 1.5 per cent this year.

Just this week NAB upped a number of its owner-occupied and investment fixed rate loans.

“There are a range of factors that influence the funding that NAB — and all Australian banks — source, so we can provide home loans to our customers,” NAB Chief Operating Officer, Antony Cahill, said of the announcement.

“The cost of providing our fixed rate home loans has increased over recent months.”

So as interest rates rise and leave mortgage holders in its dust, it leaves a huge section of society, and our economy, exposed and at risk.

NOT TERRIBLY SURPRISING

Martin North, Principal of Digital Finance Analytics, said the results are concerning, albeit not surprising.

“If you look at what people have been doing, people have been buying into property because they really believe that it is the best investment. Property prices are rising and interest rates are very low, which means they are prepared to stretch as far as they can to get into the market,” Mr North told news.com.au.

But the widespread assumption that interest rates will remain at historic lows is a disaster waiting to happen, especially in an environment where wage growth is stagnant.

“If you go back to 2005, before the GFC, people got out of jail because their incomes grew a lot faster than house prices, and therefore mortgage costs. But the trouble is that this time around we are not seeing any evidence of real momentum in income growth,” Mr North said.

“My concern is a lot of households are quite close to the edge now — they are not going to get out of jail because their incomes are going to rise. We are in a situation where interest rates are likely to rise irrespective of what the RBA does … There has already been movement up.”

Australia’s wages grew at the slowest pace on record in the three months to September 2016, according to the latest Wage Price Index released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

And as a result Australia’s debt-to-income ratio is astronomical. The ratio of household debt to disposable income has almost tripled since 1988, from 64 per cent to 185 per cent, according to the latest AMP. NATSEM Income and Wealth report.

What this means is that many Australian households are highly indebted, thanks in large part to the property market, without the income growth to pay it down.

“The ratio of debt to income is as high as it’s ever been in Australia and there are some households that are very, very exposed,” Mr North said.

THE YOUNG AND RICH MOST AT RISK

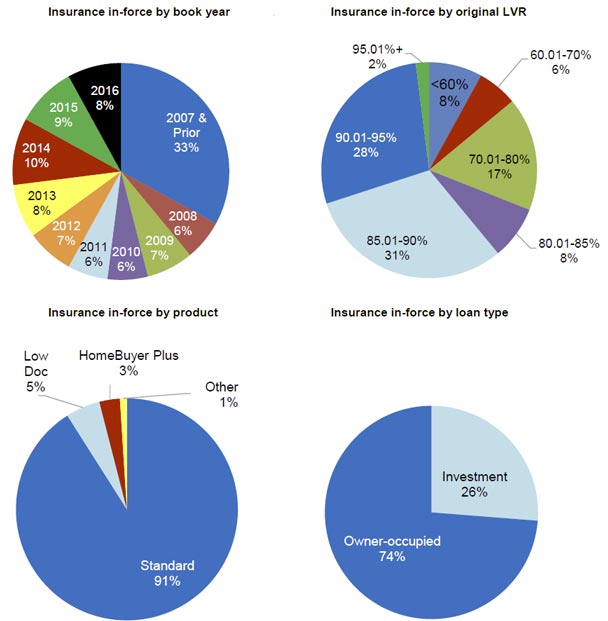

This finding will come as a surprise: young affluent homeowners are the most at risk — it is not just a problem with struggling families on the urban fringe. When it comes to this segment of the market, around 70 per cent would be in difficulty with a 0.5 per cent or less rise. If rates were to hike 3 per cent, bringing them to around the long term average of 7 per cent, nine in ten young affluent homeowners would feel the pressure.

“It is not necessarily the ones you think would be caught. And that’s because they are actually more able to get the bigger mortgage because they’ve got the bigger income to support it.

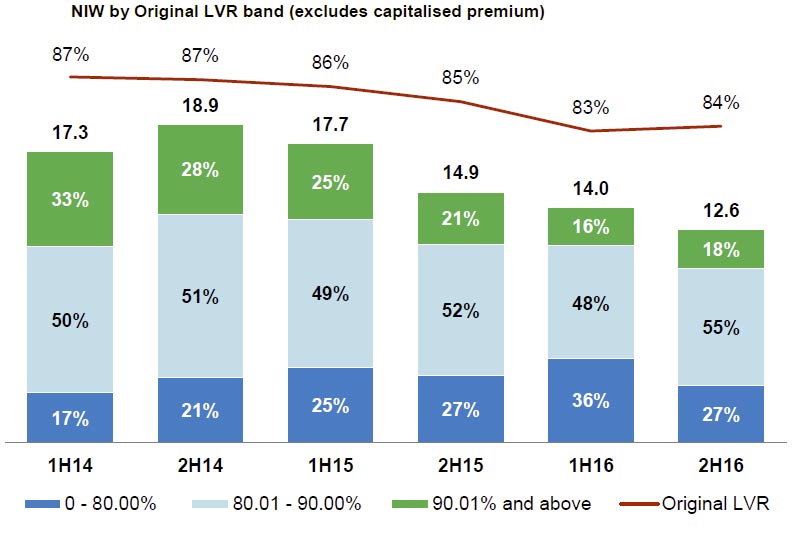

“They have actually extended themselves very significantly to get that mortgage — they have bought in an area where the property prices are high, they have got a bigger mortgage, they have got a higher LVR [loan-to-valuation ratio] mortgage and they have also got lot of other commitments. They are usually the ones with high credit card debts and a lifestyle that is relatively affluent. They are not used to handling tight budgets and watching every dollar.”

And while the younger wealthy segment of the market being most at risk might not be of that much importance compared to other segments, Mr North said what is concerning is the intense focus on this market.

“Any household group that is under pressure is a problem for the broader economy because if these people are under pressure they are not going to be spending money on retail and the broader economy,” Mr North told news.com.au.

“The banks tend to focus in on what they feel are the lower risk segments and the young affluent sector has actually been quite a target for the lending community in the last 18 months. Be that investment properties or first time owner-occupied properties, my point is there is more risk in that particular sector than perhaps the industry recognises.”

TOUGHER HOME LOAN RESTRICTIONS NEEDED

Now an argument is mounting that Australian banks need to toughen up their approach to home lending.

“I think we have got a situation where the information that is being captured by the lenders is still not robust enough. I am seeing quite often lenders willing to lend what I would regard as relatively sporty bets … I’m questioning whether the underwriting standards are tight enough,” Mr North said.

This includes accepting financial help from relatives for a deposit, a growing trend among first home buyers.

“The other thing that I have discovered in my default analysis is that those who have got help from the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ to buy their first property are nearly twice as likely to end up in difficulty … It potentially opens them to more risk later because they haven’t had the discipline of saving.”

News.com.au contacted several banks for comment on whether they think a rethink of their underwriting standards is needed. Only one lender, Commonwealth Bank, agreed to comment, but remained vague on the topic.

“In line with our responsible lending commitments, we constantly review and monitor our loan portfolio to ensure we are maintaining our prudent lending standards and meeting our customers’ financial needs. Buffers and minimum floor rates are used when assessing loan serviceability so it is affordable for customers,” a CBA spokesman said in an emailed statement.

But Mr North said something needs to be done before we find ourselves in a property and economic downturn.

“I’m assuming that with the capital growth we have seen in the property market, it will allow people who get into significant difficulty to be able to get out, however, it’s the feedback concern that I’ve got.

“If you have got a lot of people in the one area struggling with the same situation, you might see property prices begin to slip. If we get the property price slip, and we get unemployment rising and interest rates rising at the same time, we have that perfect storm which would create quite a significant wave of difficulty.

“We need to be thinking now about how to deal with higher interest rates down the track. We can’t just say it will be fine because it won’t be,” he told news.com.au.

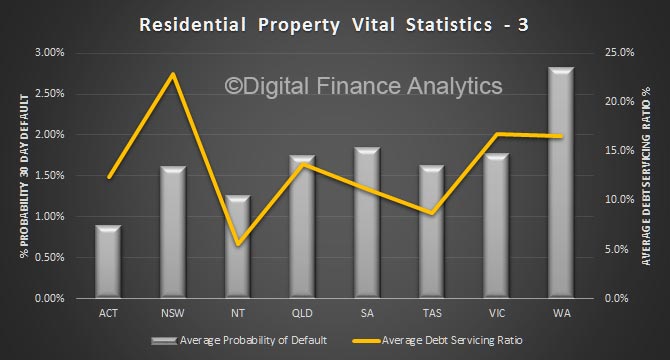

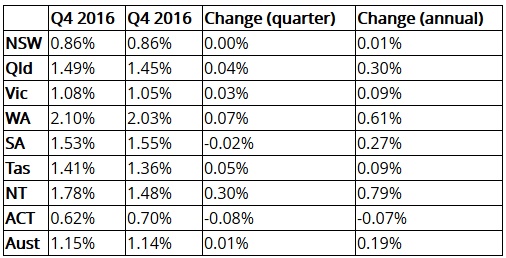

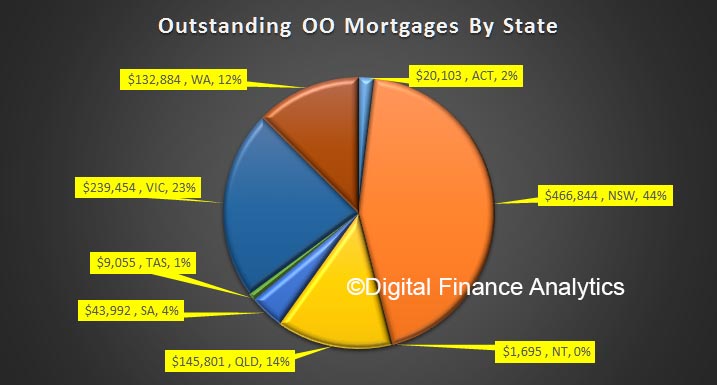

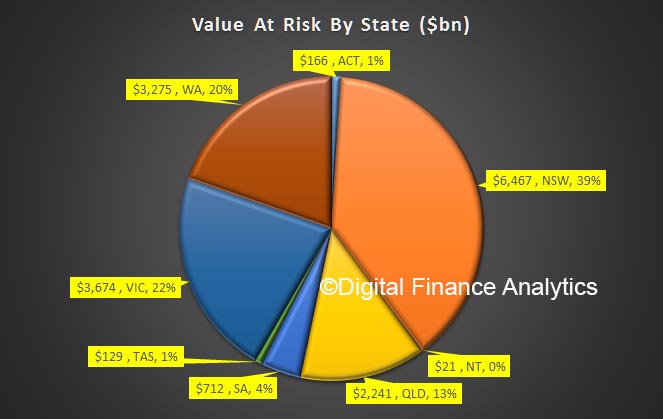

This highlights the relative higher risks in the WA mortgage portfolio, which is why lenders are being more cautious. Not all lenders are equally exposed, indeed some are targeting NSW and VIC, but WA is clearly a problem area in terms of risk assessment and management.

This highlights the relative higher risks in the WA mortgage portfolio, which is why lenders are being more cautious. Not all lenders are equally exposed, indeed some are targeting NSW and VIC, but WA is clearly a problem area in terms of risk assessment and management.