Wayne Byres opening remarks to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee in Canberra includes comments on household debt and the mortgage industry. Further evidence this is now on the supervisory agenda following recent RBA comments. Some might say, better late than never!

I will just start with a short statement of a few key issues currently on APRA’s plate.

Before I do, however, it’s important to note that Australia continues to benefit from a financial system that is fundamentally sound. That is not to say there are not challenges and problems to be addressed. However, as I’ve said elsewhere, to the extent we’re grappling with current issues and policy questions, they don’t reflect an impaired system that needs urgent remedial attention, but rather a desire to make the system stronger and more resilient while it is in good shape to do so.

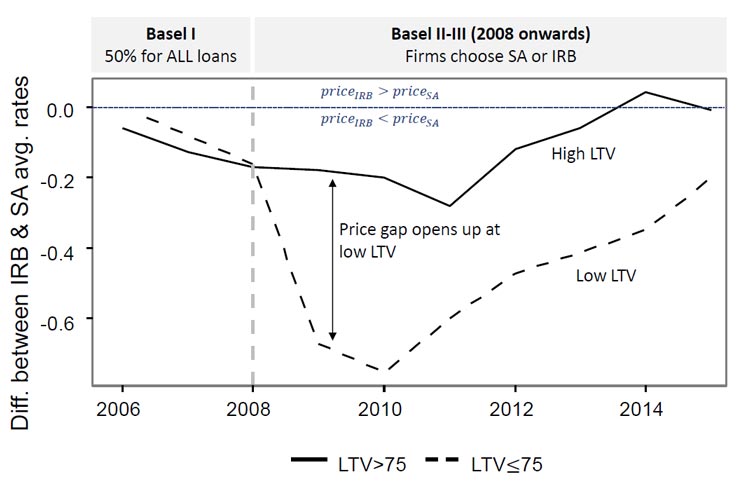

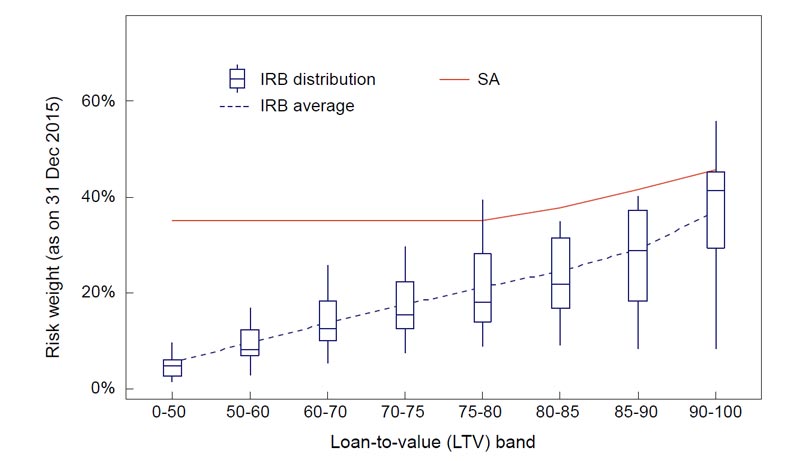

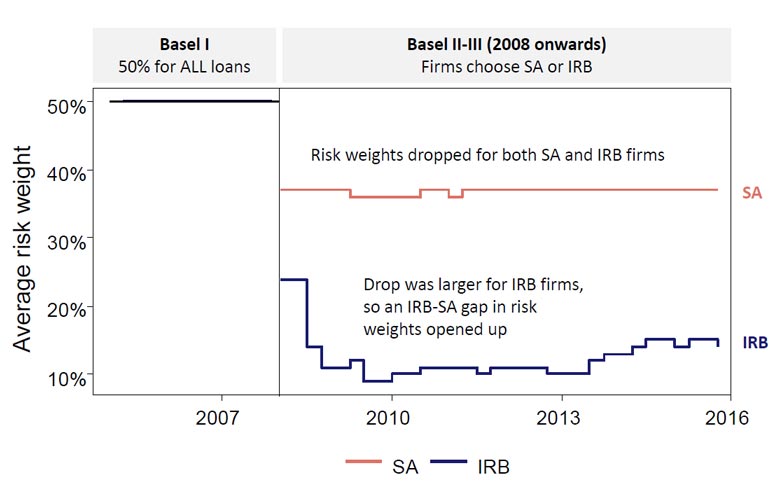

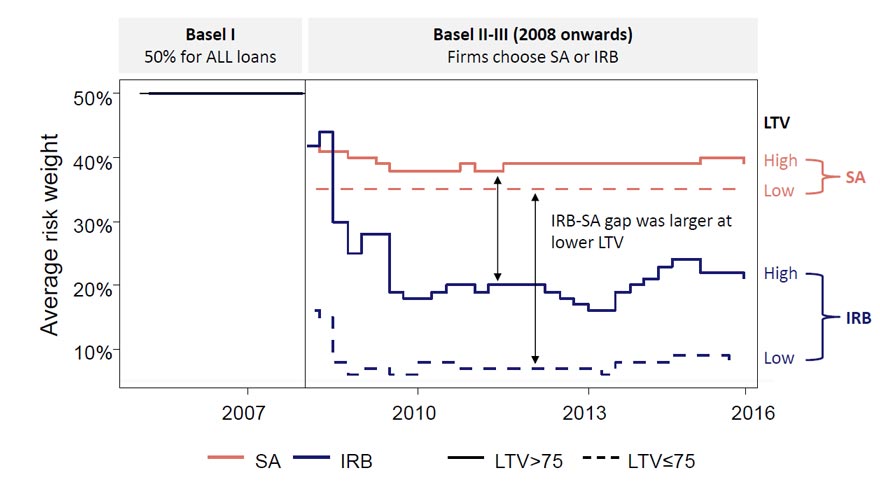

The main policy item we have on our agenda in 2017 is the first recommendation of the Financial System Inquiry (FSI): that we should set capital standards so that the capital ratios of our deposit-takers are ‘unquestionably strong.’ We had held off taking action on this until the work by the Basel Committee on the international bank capital regime had been completed. But delays to the work in Basel mean we don’t think we should wait any longer.

Our goal in implementing the FSI’s recommendation is to enhance the capital framework for deposit-takers to achieve not only greater resilience, but also increased flexibility and transparency. And in doing all this, we will also be working to enable affected institutions to adjust to any policy changes in an orderly manner. If we achieve our goals, we will not only deliver improved safety and stability within the financial system, we will also aid other important considerations such as competition and efficiency.

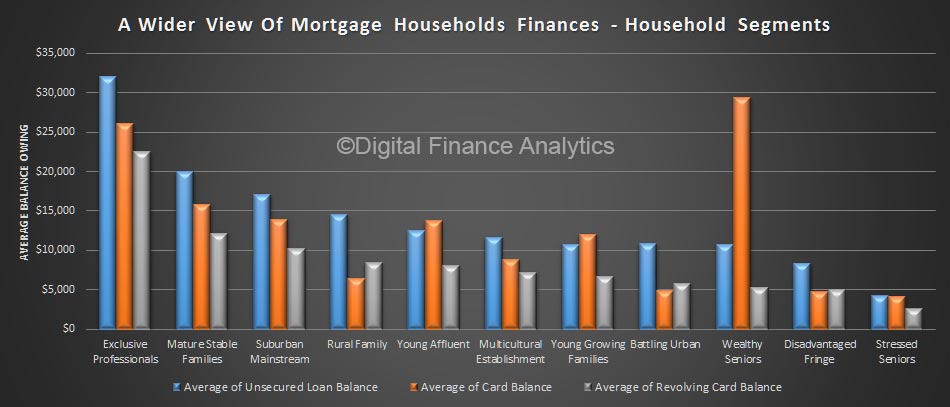

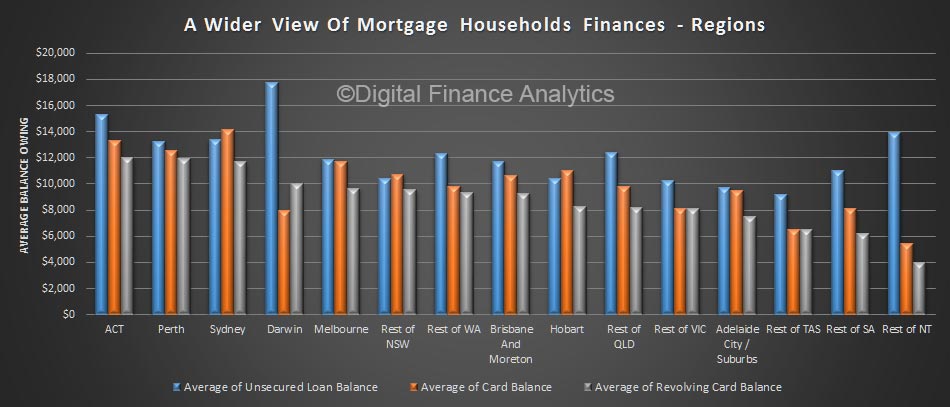

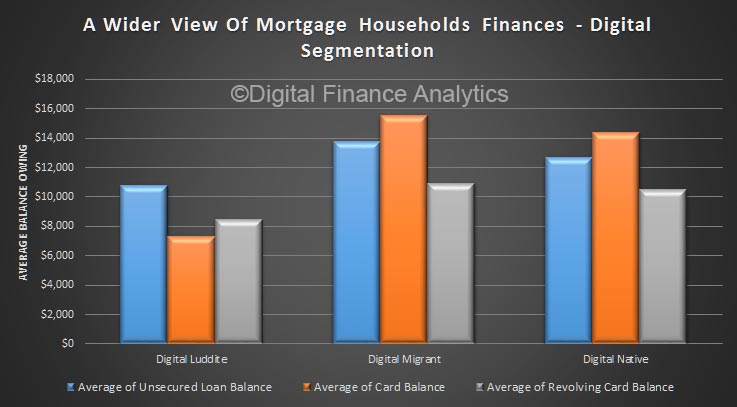

We have many supervisory challenges at present, but there is no doubt that monitoring conditions in the Australian housing market remains high on our priority list. We have lifted our supervisory intensity in a number of ways, including reinforcing stronger lending standards and seeking in particular to moderate the rapid growth in lending to investors. These efforts have had the desired impact: we can be more confident in the conservatism of mortgage lending decisions today relative to a few years ago, and lending to investors was running at double digit rates of growth but has since come back into single figures.

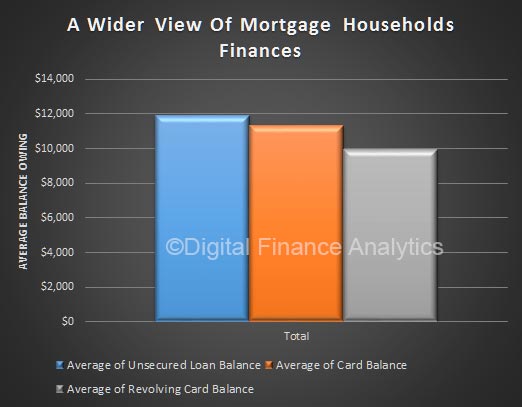

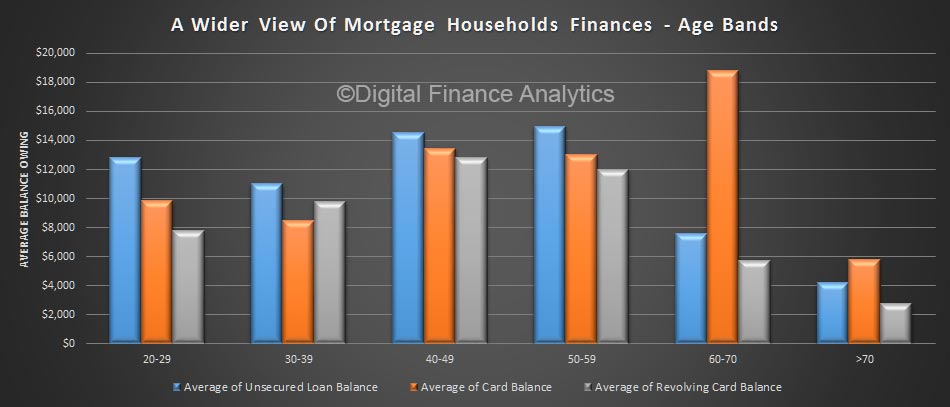

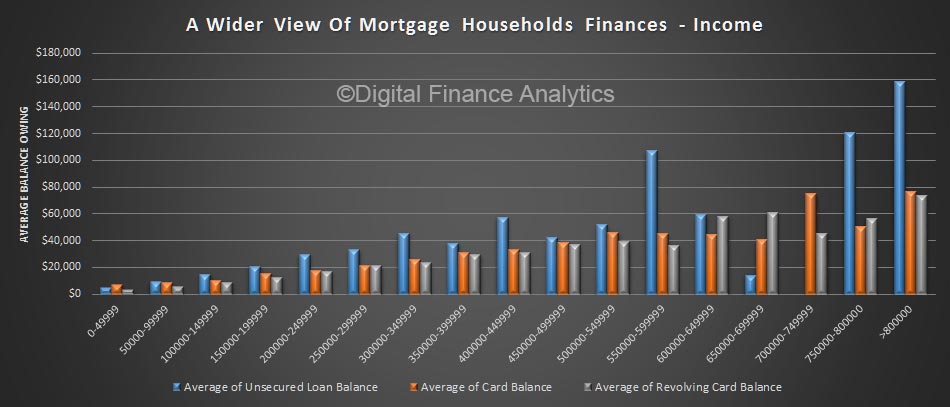

However, strong competitive pressures are producing higher rates of lending growth again. This is occurring at a time when household debt levels are already high and household income growth is subdued. The cost of housing finance is also more likely to rise than fall. We therefore see no room for complacency, and mortgage lending will inevitably remain a very important issue for us for the foreseeable future.

The final issue I wanted to mention is our work on superannuation governance. This is an area where we remain keen to lift the bar. There are some excellent examples of good practice governance in the superannuation sector, but equally there are examples where we think more can be done to make sure members’ interests are paramount. Late last year, we finalised some changes to our prudential requirements to strengthen governance frameworks. The changes we implemented were relatively uncontroversial at the time, and have largely been included within the principles for sound governance that have subsequently been generated by the industry itself.