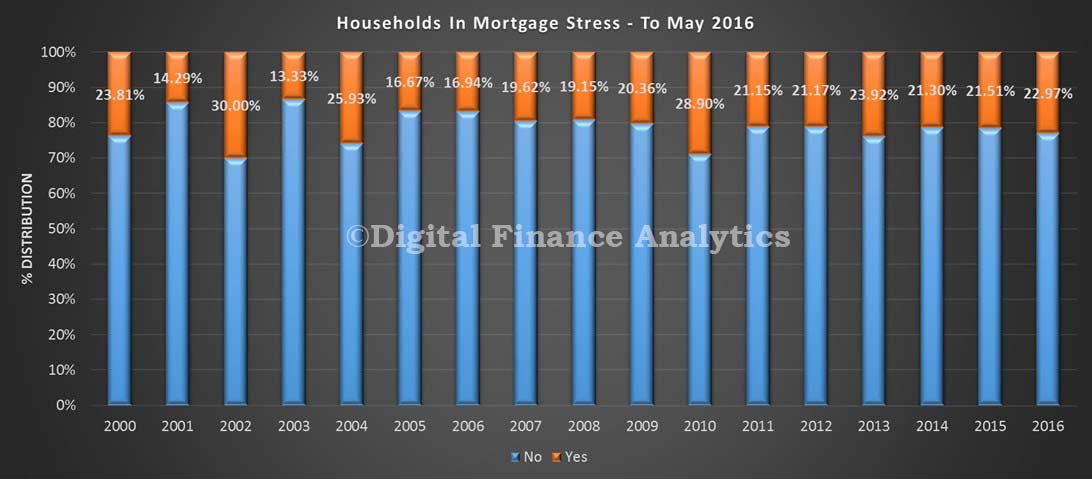

We have updated the Digital Finance Analytics Mortgage Stress Analysis, to August 2016, using data from our household surveys. Contrary to what might be thought, whilst the ultra-low mortgage rates are easing the finances of some households, mortgage stress still exists, and it’s iron hand is being felt by more than 21% of households. But it is not equally spread across the population, so you need to get granular to see what is going on. Worth though noting the Roy Morgan data we reported already, estimated 18.4% of households were in mortgage stress, so some correlation.

Over the next few days we will drill into the details to highlight where the pain is most severe, but today we start with an overview.

Before we start, we define mortgage stress, not as a fixed percentage of income servicing the mortgage, rather we examine the household budget, comparing the income with outgoings, including mortgage repayments and other commitments. Those in mortgage stress do not have sufficient free funds to pay their mortgage on time, without difficulty. You can read more about our definitions of mortgage stress here.

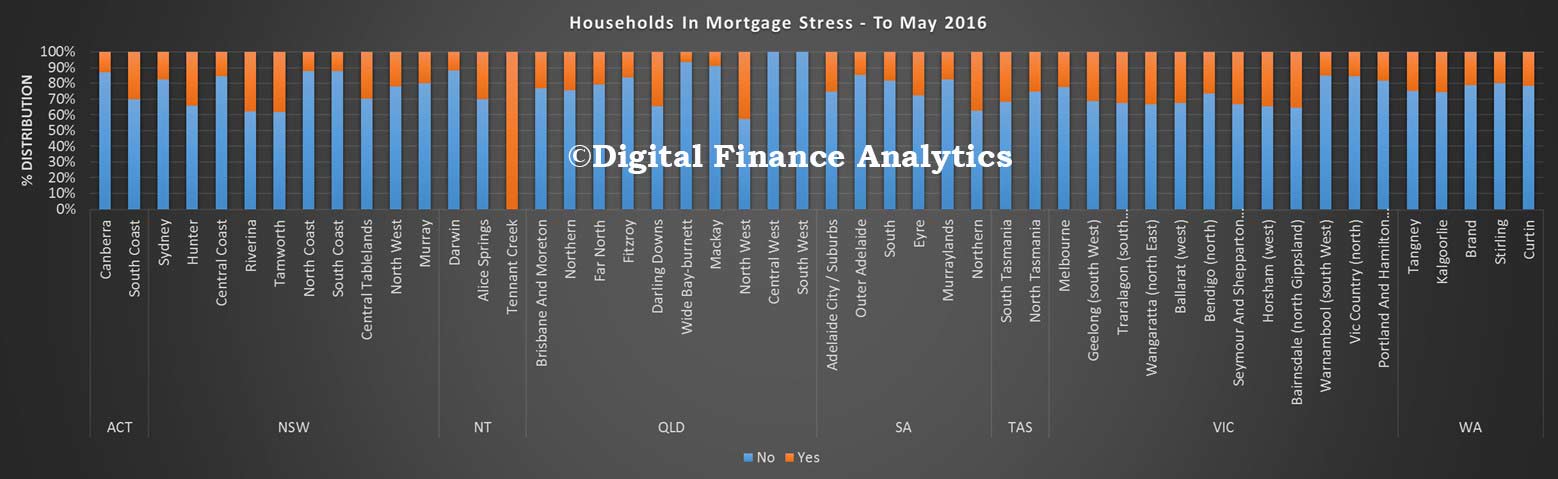

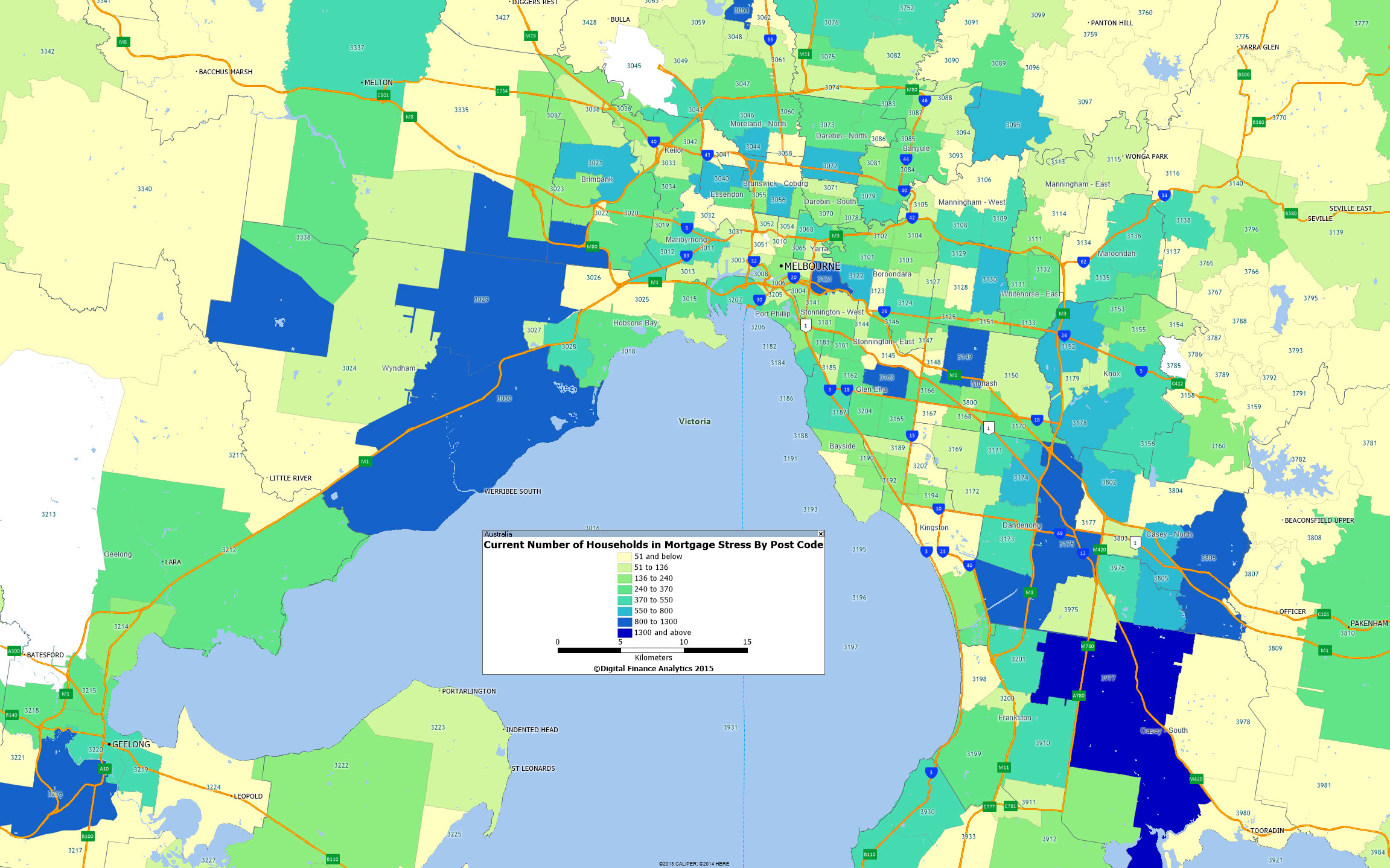

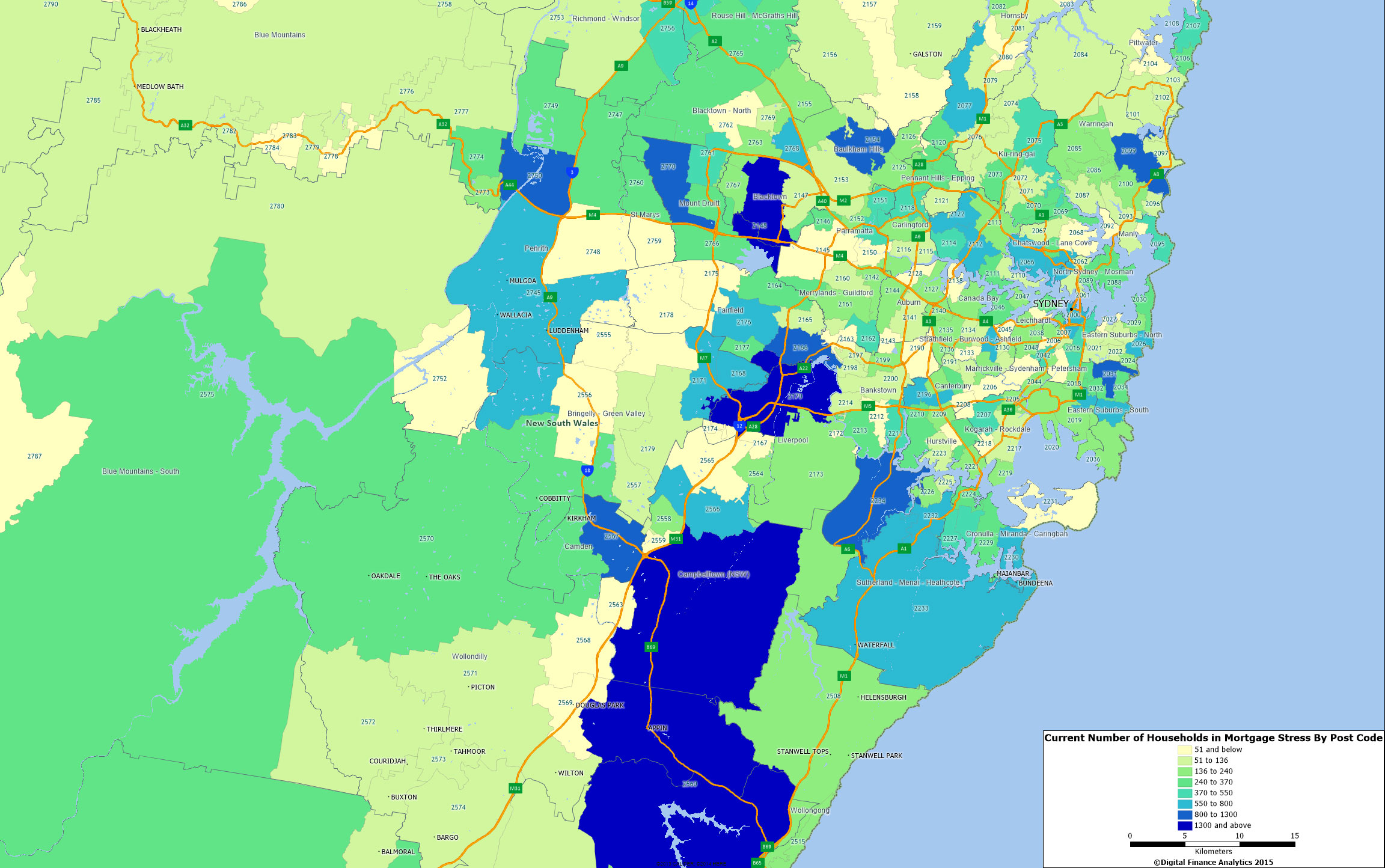

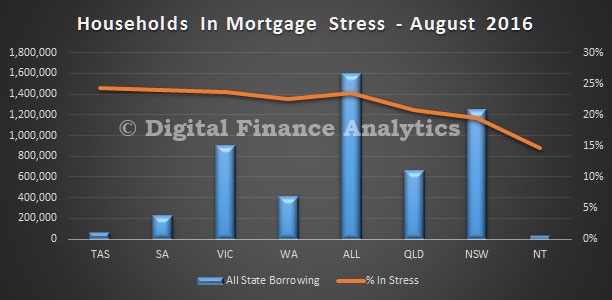

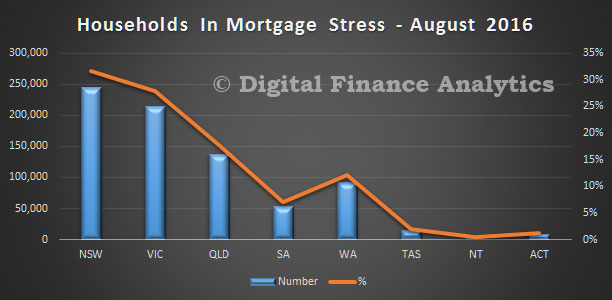

Looking at the summary analysis, the largest proportion of households who are borrowing and in mortgage stress reside in TAS and SA, then VIC, WA; all above the national average. QLD and NSW are below the average, along with NT.

In total there were 769,592 households nationally in stress. Looking at the number of households in stress by state however, NSW has the largest number with 244,119.

In total there were 769,592 households nationally in stress. Looking at the number of households in stress by state however, NSW has the largest number with 244,119.

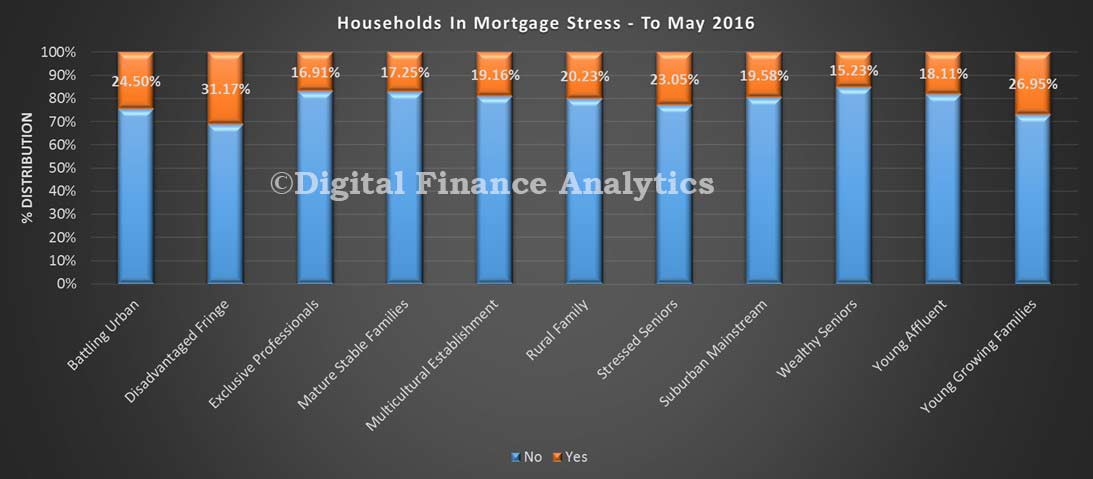

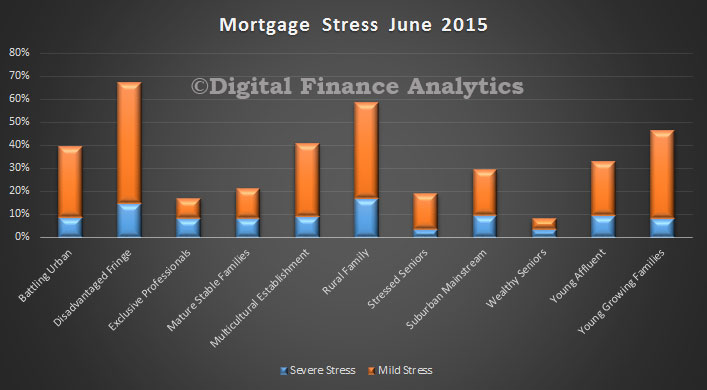

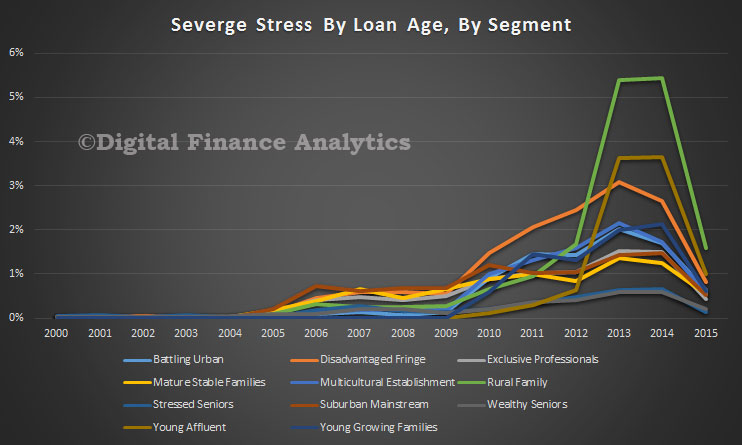

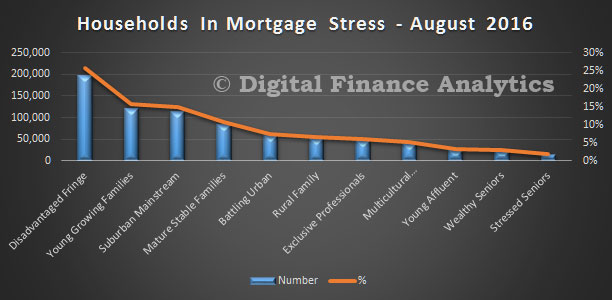

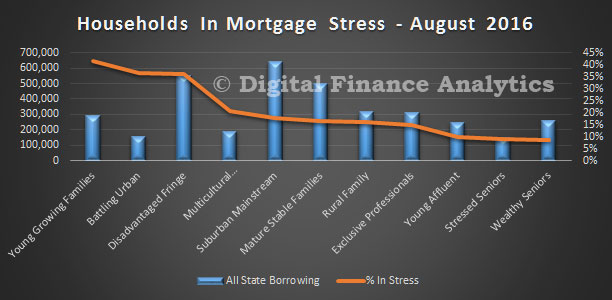

Turning to our household segments, those in the disadvantaged fringe and young growing family groups are the most strongly represented.

Turning to our household segments, those in the disadvantaged fringe and young growing family groups are the most strongly represented.

But, expressed as a percentage of segments in stress, young growing families are most exposed, with 41% in mortgage stress, slightly ahead of battling urban 36.7% and disadvantaged fringe 36%. Young affluent, stressed seniors and wealthy seniors were the least stressed.

But, expressed as a percentage of segments in stress, young growing families are most exposed, with 41% in mortgage stress, slightly ahead of battling urban 36.7% and disadvantaged fringe 36%. Young affluent, stressed seniors and wealthy seniors were the least stressed.

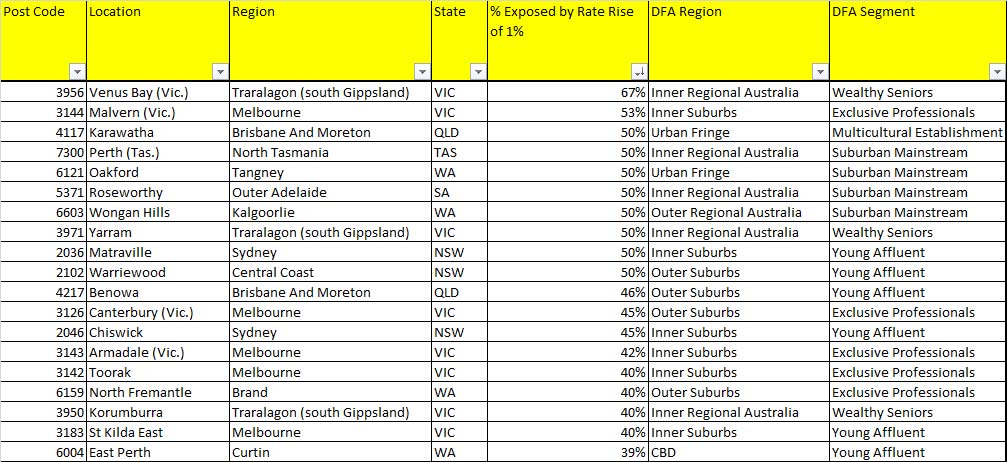

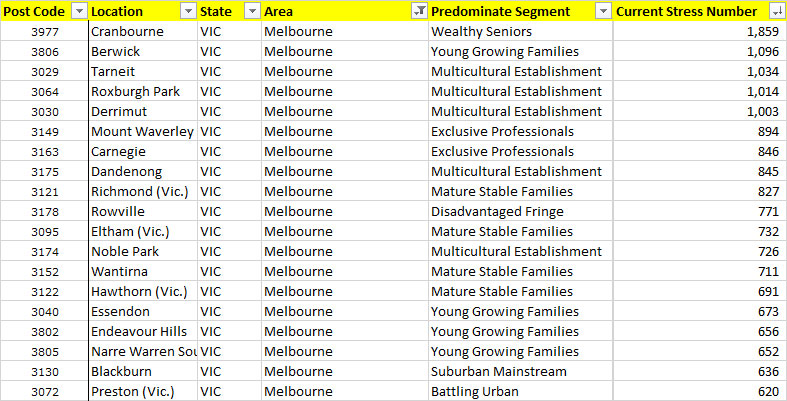

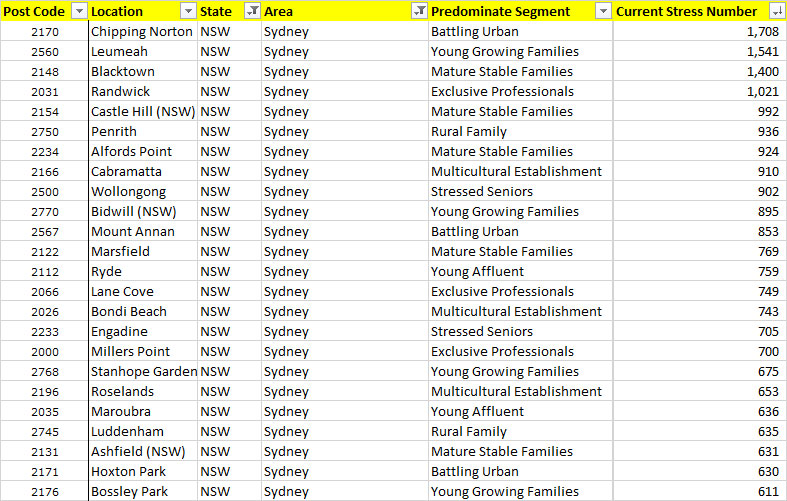

Finally, here is the top 30 or so, nationally. The most stressed post code in Australia at the moment is 4350, Harristown, with more than 7,000 households in difficulty. Note too that those at the top of the list are not necessarily as expected. Some older and more affluent segments are also being hit.

Finally, here is the top 30 or so, nationally. The most stressed post code in Australia at the moment is 4350, Harristown, with more than 7,000 households in difficulty. Note too that those at the top of the list are not necessarily as expected. Some older and more affluent segments are also being hit.

Next time we will look in more detail at some of the states, and discuss the underlying causes of mortgage stress. But for now, it is clear that mortgage stress is still a very significant economic factor.

Next time we will look in more detail at some of the states, and discuss the underlying causes of mortgage stress. But for now, it is clear that mortgage stress is still a very significant economic factor.