An important announcement from APRA today that Australian banks are mandated to prepare for negative interest rates.

Go to the Walk The World Universe at https://walktheworld.com.au/

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

An important announcement from APRA today that Australian banks are mandated to prepare for negative interest rates.

Go to the Walk The World Universe at https://walktheworld.com.au/

We look at the latest trends on Australian Bonds, Credit Markets and the recent IMF paper on negative interest rates – which they link to the need to restrict cash. This will not end well.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/03/what-are-negative-interest-rates-basics.htm

We look at the latest trends on Australian Bonds, Credit Markets and the recent IMF paper on negative interest rates – which they link to the need to restrict cash. This will not end well.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/03/what-are-negative-interest-rates-basics.htm

Hot off the press – How Can Interest Rates Be Negative? – we get the latest missive from the IMF which confirms precisely what we have been saying.

But the concern remains about the limits to negative interest rate policies so long as cash exists as an alternative.

Here is the article. Read, and weep….

Money has been around for a long time. And we have always paid for using someone else’s money or savings. The charge for doing this is known by many different words, from prayog in ancient Sanskrit to interest in modern English. The oldest known example of an institutionalized, legal interest rate is found in the Laws of Eshnunna, an ancient Babylonian text dating back to about 2000 BC.

For most of history, nominal interest rates—stated rates that borrowers pay on a loan—have been positive, that is, greater than zero. However, consider what happens when the rate of inflation exceeds the return on savings or loans. When inflation is 3 percent, and the interest rate on a loan is 2 percent, the lender’s return after inflation is less than zero. In such a situation, we say the real interest rate—the nominal rate minus the rate of inflation—is negative.

In modern times, central banks have charged a positive nominal interest rate when lending out short-term funds to regulate the business cycle. However, in recent years, an increasing number of central banks have resorted to low-rate policies. Several, including the European Central Bank and the central banks of Denmark, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland, have started experimenting with negative interest rates —essentially making banks pay to park their excess cash at the central bank. The aim is to encourage banks to lend out those funds instead, thereby countering the weak growth that persisted after the 2008 global financial crisis. For many, the world was turned upside down: Savers would now earn a negative return, while borrowers get paid to borrow money? It is not that simple.

Simply put, interest is the cost of credit or the cost of money. It is the amount a borrower agrees to pay to compensate a lender for using her money and to account for the associated risks. Economic theories underpinning interest rates vary, some pointing to interactions between the supply of savings and the demand for investment and others to the balance between money supply and demand. According to these theories, interest rates must be positive to motivate saving, and investors demand progressively higher interest rates the longer money is borrowed to compensate for the heightened risk involved in tying up their money longer. Hence, under normal circumstances, interest rates would be positive, and the longer the term, the higher the interest rate would have to be. Moreover, to know what an investment effectively yields or what a loan costs, it important to account for inflation, the rate at which money loses value. Expectations of inflation are therefore a key driver of longer-term interest rates.

While there are many different interest rates in financial markets, the policy interest rate set by a country’s central bank provides the key benchmark for borrowing costs in the country’s economy. Central banks vary the policy rate in response to changes in the economic cycle and to steer the country’s economy by influencing many different (mainly short-term) interest rates. Higher policy rates provide incentives for saving, while lower rates motivate consumption and reduce the cost of business investment. A guidepost for central bankers in setting the policy rate is the concept of the neutral rate of interest : the long-term interest rate that is consistent with stable inflation. The neutral interest rate neither stimulates nor restrains economic growth. When interest rates are lower than the neutral rate, monetary policy is expansionary, and when they are higher, it is contractionary.

Today, there is broad agreement that, in many countries, this neutral interest rate has been on a clear downward trend for decades and is probably lower than previously assumed. But the drivers of this decline are not well understood. Some have emphasized the role of factors like long-term demographic trends (especially the aging societies in advanced economies), weak productivity growth, and the shortage of safe assets. Separately, persistently low inflation in advanced economies, often significantly below their targets or long-term averages, appears to have lowered markets’ long-term inflation expectations. The combination of these factors likely explains the striking situation in today’s bond markets: not only have long-term interest rates fallen, but in many countries, they are now negative.

Returning to monetary policy, following the global financial crisis, central banks cut nominal interest rates aggressively, in many cases to zero or close to zero. We call this the zero lower bound, a point below which some believed that interest rates could not go. But monetary policy affects an economy through similar mechanics both above and below zero. Indeed, negative interest rates also give consumers and businesses an incentive to spend or invest money rather than leave it in their bank accounts, where the value would be eroded by inflation. Overall, these aggressively low interest rates have probably helped somewhat, where implemented, in stimulating economic activity, though there remain uncertainties about side effects and risks.

A first concern with negative rates is their potential impact on bank profitability. Banks perform a key function by matching savings to useful projects that generate a high rate of return. In turn, they earn a spread, the difference between what they pay savers (depositors) and what they charge on the loans they make. When central banks lower their policy rates, the general tendency is for this spread to be reduced, as overall lending and longer-term interest rates tend to fall. When rates go below zero, banks may be reluctant to pass on the negative interest rates to their depositors by charging fees on their savings for fear that they will withdraw their deposits. If banks refrain from negative rates on deposits, this could in principle turn the lending spread negative, because the return on a loan would not cover the cost of holding deposits. This could in turn lower bank profitability and undermine financial system stability.

A second concern with negative interest rates on bank deposits is that they would give savers an incentive to switch out of deposits into holding cash. After all, it is not possible to reduce cash’s face value (though some have proposed getting rid of cash altogether to make deeply negative rates feasible when needed). Hence there has been a concern that negative rates could reach a tipping point beyond which savers would flood out of banks and park their money in cash outside the banking system. We don’t know for sure where such an effective lower bound on interest rates is. In some scenarios, going below this lower bound could undermine financial system liquidity and stability.

In practice, banks can charge other fees to recoup costs, and rates have not gotten negative enough for banks to try to pass on negative rates to small depositors (larger depositors have accepted some negative rates for the convenience of holding money in banks). But the concern remains about the limits to negative interest rate policies so long as cash exists as an alternative.

Overall, a low neutral rate implies that short-term interest rates could more frequently hit the zero lower bound and remain there for extended periods of time. As this occurs, central banks may increasingly need to resort to what were previously thought of as unconventional policies, including negative policy interest rates.

No, central banks are taking us down a blind alley!

We discuss a new Bank of England paper. And it turns current central banking thinking on its head!

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/working-paper/2020/eight-centuries-of-global-real-interest-rates-r-g-and-the-suprasecular-decline-1311-2018

The normal line of argument has been that its central banks pumping liquidity into the financial markets which have led to falling real interest rates, and that they might indeed take them into negative territory. This is all to do with “secular stagnation” (reflecting poor productivity, globalisation, weak wages growth, and monetary policy intervention by central banks).

Last year the IMF in a working paper suggested that a cut of 4% or there abouts would be required to react to a financial crisis similar to the scale of the GFC. That would pull rates deeply negative, and of course so far (Sweden apart) no one has found a way back, as Japan and the Eurozone illustrates.

Many sovereign rates sit in negative territory, and there is an unprecedented $10 trillion in negative-yielding debt. This new interest rate climate has many observers wondering where the bottom truly lies.

Now, most economists are on a quest to return to a “stable positive rate”, eventually, considering negative rates to be there for am emergency, and temporary.

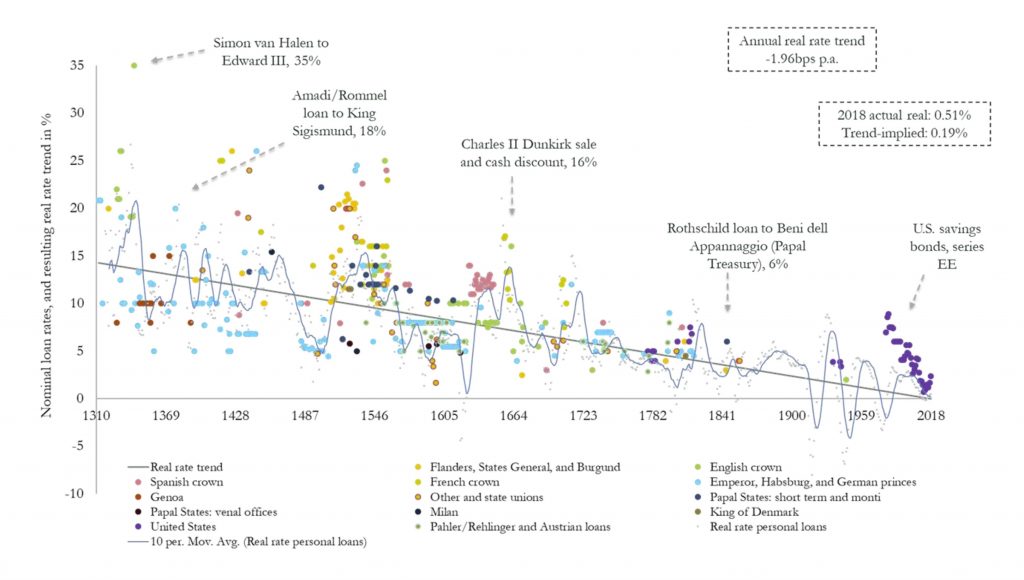

But a working paper from the Bank of England Eight centuries of global real interest rates, R-G, and the ‘suprasecular’ decline, 1311–2018 by Paul Schmelzing really puts the cat among the pigeons.

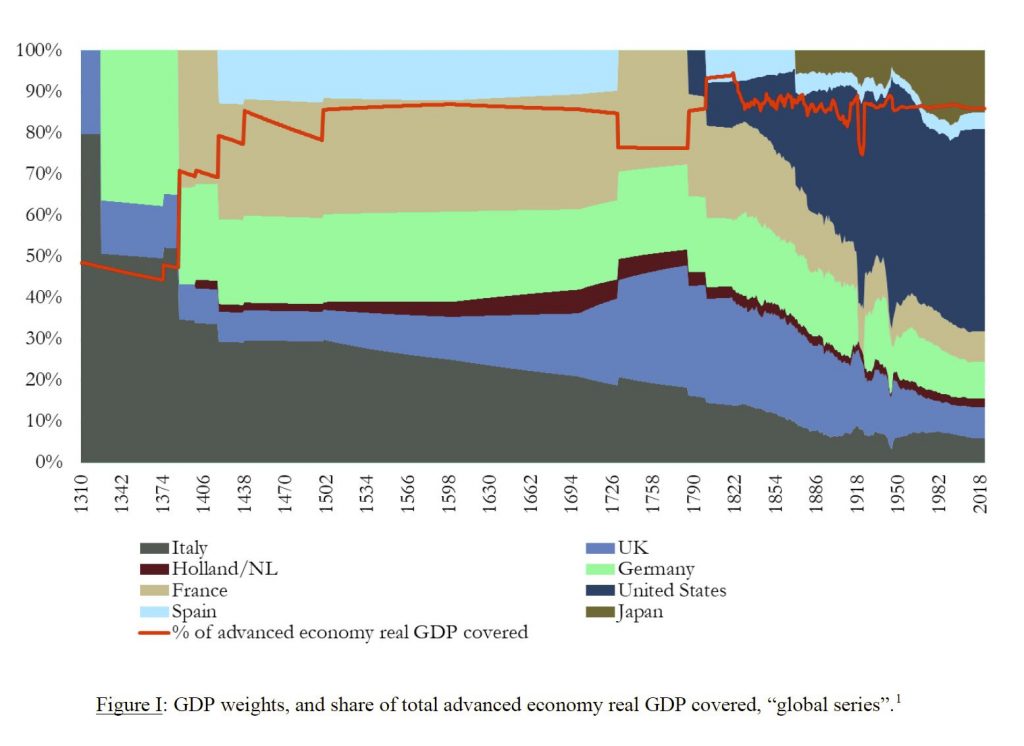

The paper creates a long term global series, weighted by GDP from 1310 to the present day. The series only includes yields which are not contracted short-term, which are not paid in-kind, which are not clearly of an involuntary nature, which are not intra-governmental, and which are made to executive political bodies. In other words, cash lending against annual payments in “chicken” and other commodities, or against leases for offices, against jewellery, land or other real estate with no known equivalent cash value are all excluded.

The GDP weights over time, and the share of advanced economy GDP covered by the series varies as history played out and empires rose and fell.

Data robustness is an issue, as the paper recognises as late medieval and early modern data can of course never be established with the same granularity as modern high-frequency statistics. One still has to rely on interpolations, deal with the peculiarities of early modern finance, and acknowledge that the permanency of wars, disasters, and destitution since medieval times may have irrecoverably destroyed a significant share of the evidence desired. However, the story is pretty clear.

The data here suggests that the “historically implied” safe asset provider long-term real rate stands at 1.56% for the year 2018, which would imply that against the backdrop of inflation targets at 2%, nominal advanced economy rates may no longer rise sustainably above 3.5%. Whatever the precise dominant driver –simply extrapolating such long-term historical trends suggests that negative real rates will not just soon constitute a “new normal” – they will continue to fall constantly. By the late 2020s, global short-term real rates will have reached permanently negative territory. By the second half of this century, global long-term real rates will have followed.

The standard deviation of the real rate – its “volatility” – meanwhile, has shown similar properties over the last 500 years: fluctuations in benchmark real rates are steadily declining, implying that rate levels are set to become both lower, and stickier. But downward-trending absolute levels, and declining volatilities have persisted against a backdrop of a secularly growing importance of public and monetary balance sheets. This would suggest that expansionary monetary and fiscal policy responses designed to raise real interest rates from current levels may at best have a cyclical effect in the longer-term context.

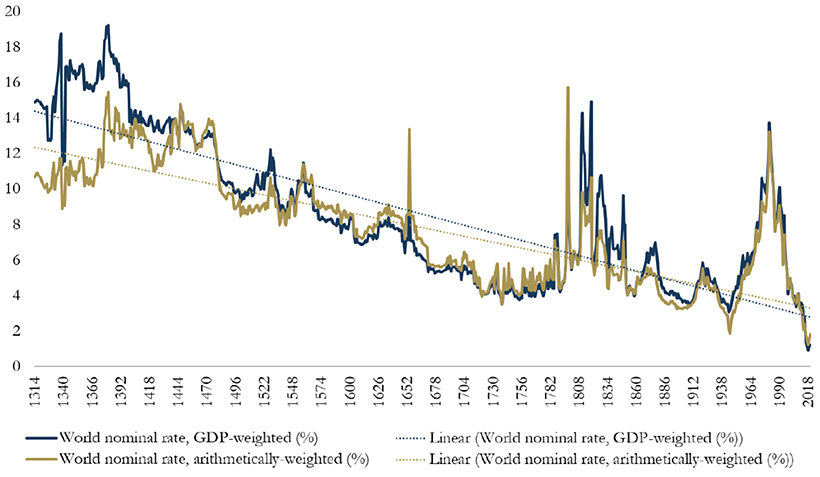

According to the report, another trend has coincided with falling interest rates: declining bond yields. Since the 1300s, global nominal bonds yields have dropped from over 14% to around 2%.

He concludes:

I sought to suggest that a long-term reconstruction of real rate developments points towards key revisions concerning at least two major current debates directly based on – or deriving from – the narrative about long-term capital returns.

First, my new data showed that long-term real rates – be it in the form of private debt, non-marketable loans, or the global sovereign “safe asset” – should always have been expected to hit “zero bounds” around the time of the late 20th and early 21st century, if put into long-term historical context.

In fact, a meaningful – and growing – level of long-term real rates should have been expected to record negative levels. There is little unusual about the current low rate environment which the “secular stagnation” narrative attempts to display as an unusual aberration, linked to equally unusual trend-breaks in savings-investment balances, or productivity measures. To extent that such literature then posits particular policy remedies to address such alleged phenomena, it is found to be fully misleading: the trend fall in real rates has coincided with a steady long-run uptick in public fiscal activity; and it has persisted across a variety of monetary regimes: fiat- and non-fiat, with and without the existence of public monetary institutions.

Secondly, sovereign long-term real rates have been placed into context to other key components of “nonhuman wealth returns” over the (very) long run, including private debt, and real land returns, together with a suggestion that fixed income-linked wealth has historically assumed a meaningful share of private wealth. There is a very high probability, therefore, to suggest that “non-human wealth” returns have by no means been “virtually stable”, only if business investments have both shown an extreme increase in real returns, and an extreme increase in their total wealth share, could the framework be saved.

If compared to real income growth dynamics we equally detect a downward trend across all assets covered in the above discussion.

There is no reason, therefore, to expect rates to “plateau”, to suggest that “the global neutral rate may settle at around 1% over the medium to long run”, or to proclaim that “forecasts that the real rate will remain stuck at or below zero appear unwarranted” as some have suggested.

With regards to policy, very low real rates can be expected to become a permanent and protracted monetary policy problem – but my evidence still does not support those that see an eventual return to “normalized” levels however defined, who contemplate a “nadir” in global real rates in the 2020s): the long-term historical data suggests that, whatever the ultimate driver, or combination of drivers, the forces responsible have been indifferent to monetary or political regimes; they have kept exercising their pull on interest rate levels irrespective of the existence of central banks, (de jure) usury laws, or permanently higher public expenditures. They persisted in what amounted to early modern patrician plutocracies, as well as in modern democratic environments, in periods of low-level feudal Condottieri battles, and in those of professional, mechanized mass warfare.

In the end, then, it was the contemporaries of Jacques Coeur and Konrad von Weinsberg – not those in the financial centres of the 21st century – who had every reason to sound dire predictions about an “endless inegalitarian spiral”. And it was the Welser in early 16th century Nuremberg, or the Strozzi of Florence in the same period, who could have filled their business diaries with reports on the unprecedented “secular stagnation” environment of their days. That they did not do so serves not necessarily to illustrate their lack of economic-theoretical acumen: it should rather put doubt on the meaningfulness of some of today’s concepts.

So negative rates are coming and are here to stay!

If you think restricting cash has nothing to do with monetary policy and negative interest rates, then watch this.

We look at a recent CNN Business article looking at the Swiss.

Time to buy a safe?

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/01/23/investing/switzerland-cash-negative-rates/index.html

[Recorded in a thunderstorm…]

If you think restricting cash has nothing to do with monetary policy and negative interest rates, then watch this.

We look at a recent CNN Business article looking at the Swiss.

Time to buy a safe?

[Recorded in a thunderstorm…]

Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North look at recent Hansard records where the Banks discussed their plans for negative interest rates.

The link between the Cash Restrictions Bill and potential Negative Rates are very real, no conspiracy theory here – but fact!

We review the recent BIS paper which highlights the issues with low interest rates.