The Reserve Bank NZ, has issued a Consultation Paper: Review of the Capital Adequacy Framework for locally incorporated banks: calculation of risk weighted assets.

This is the third consultation document of the review. The first document provided an overview of the review. The second document considered the definition of capital, which is the numerator in the minimum regulatory capital ratio. This document is concerned with the denominator in the minimum capital ratio, which is effectively a measure of exposure to risk.

They highlight further issues with the internal calculation method, as well as recent changes from the Basel Committee.

There is international and New Zealand evidence that minimum capital requirements went down significantly after banks were permitted to use their internal models for parts of the capital calculation. There is also international evidence that internal model outcomes are inconsistent. Different banks often come up with similar rankings of risk but the absolute levels of risk are substantially different even for the same obligors. The evidence is clearest in the case for exposures to governments, banks, and large corporations, but there is also some evidence of problems in other portfolios such as residential mortgages and SME lending.

The Basel Committee had proposed to replace the IRB approach with the standardised approach for bank and large corporate exposures, and with a standardised or semi-standardised approach for all specialised lending to corporates. The finalised framework did not go this far – it continues to allow a more limited form of IRB modelling, the Foundation IRB (F-IRB) approach, for bank and large corporate exposures. The new framework does, as originally proposed, constrain the outputs of internal models and impose an overall floor – based on the risk assessed under the standardised approach – on the average risk weight, to prevent it from straying too far from a common level.

Specifically, there are currently significant differences between the two approaches. Banks with internal models have a significant capital advantage.

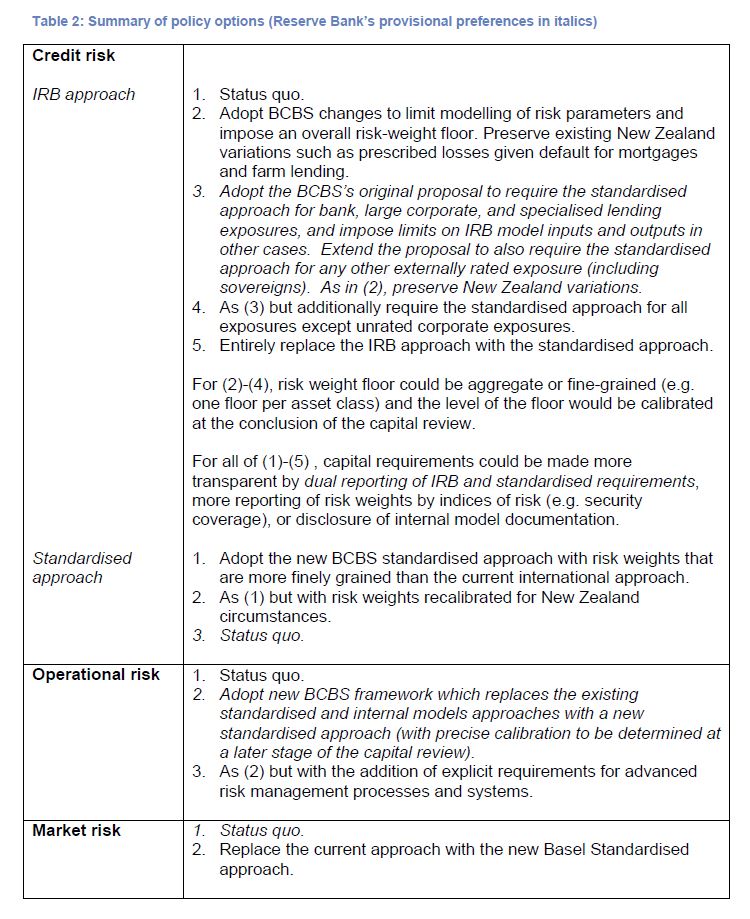

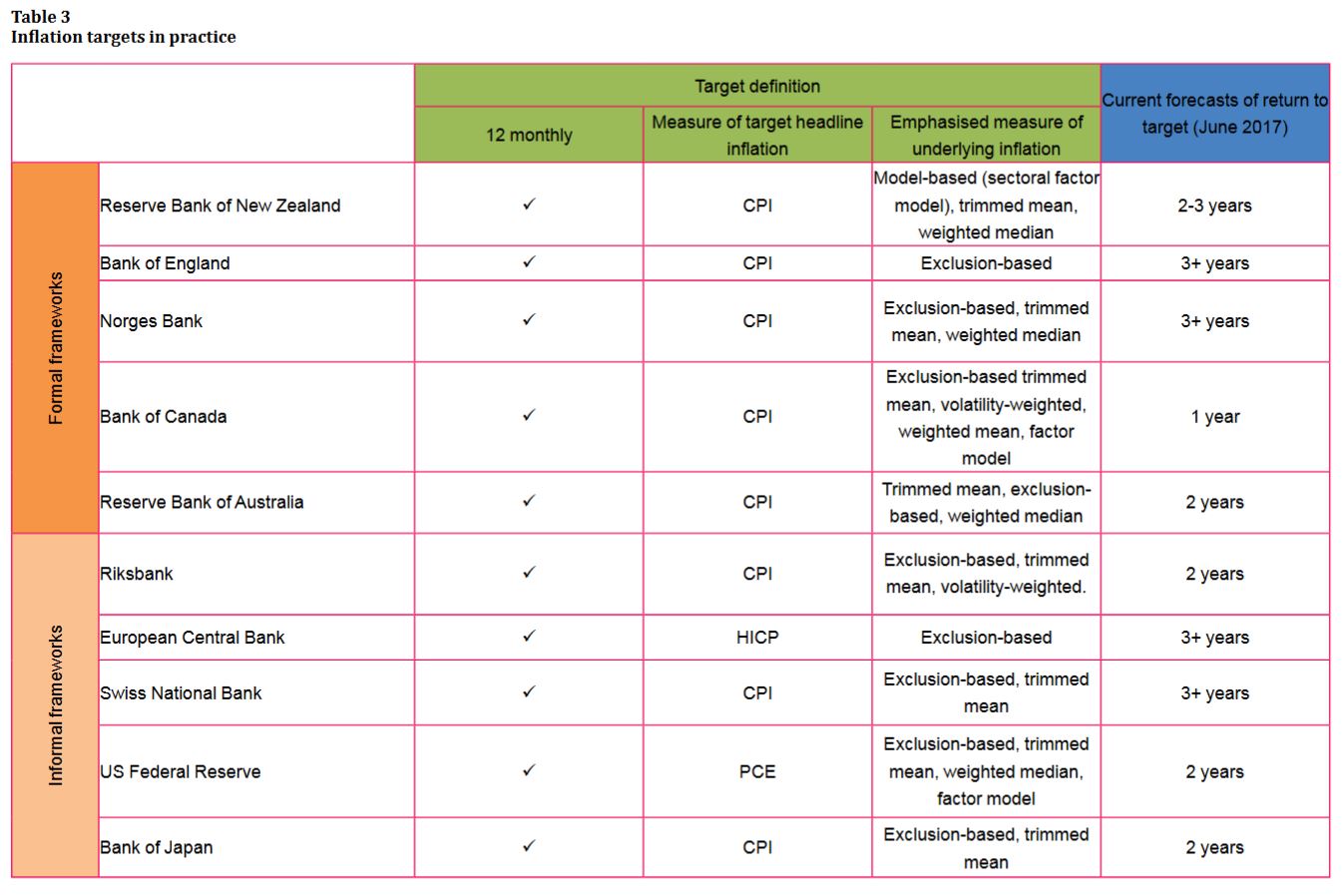

They table options for both internal and standard approaches, as below.

They table options for both internal and standard approaches, as below.