Many economically advanced countries are failing to fully enforce regulations on political party funding and campaign donations or are leaving loopholes that can be exploited by powerful private interest groups, according to a new OECD report.

Financing Democracy: Funding of Political Parties and Election Campaigns and the Risk of Policy Capture says that private donors frequently use loans, membership fees and third-party funding to circumvent spending limits or to conceal donations. Tightening regulation and applying sanctions more rigorously would help to restore public trust at a time when voters in advanced economies are showing disillusionment with political parties and fear that democratic processes can be captured by private interest groups.

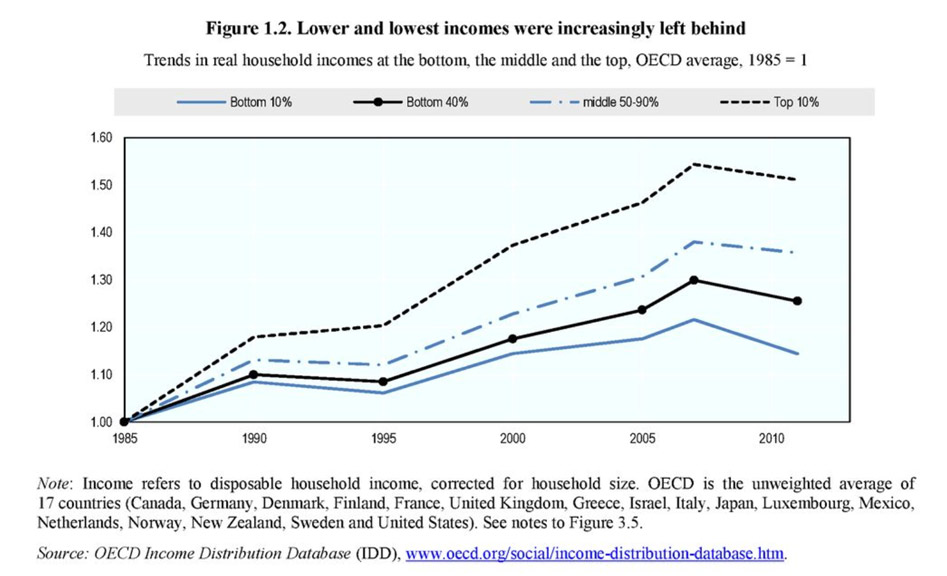

“Policy making should not be for sale to the highest bidder,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría, launching the Organisation’s first report on political financing at a meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network, a forum for legislators from member and partner countries to compare policies and discuss best practices. “When policy is influenced by wealthy donors, the rules get bent in favour of the few and against the interests of the many. Upholding rigorous standards in political finance is a key part of our battle to reduce inequality and restore trust in democracy,” he said.

Many countries struggle to define and regulate “third-party” campaigning by organisations or individuals who are not political parties or candidates, enabling election spending to be channelled through supposedly independent committees and interest groups. Only a handful of countries have regulations on third-party campaigning, and these regulations vary in strictness.

Globalisation is complicating the regulation of political party funding as multinational companies and wealthy foreign individuals are increasingly integrated with domestic business interests. Where limits and bans on foreign and corporate funding exist, disclosure of donor identity is a vital deterrent to misuse of influence. While 17 of the 34 OECD countries ban anonymous donations to political parties, 13 only ban them above certain thresholds and four allow them.

Even when donations are not anonymous, countries have differing rules about disclosing donor identity. In nine OECD countries political parties are obliged to publically disclose the identity of donors, while in the other 25 OECD countries parties do so on an ad-hoc basis.

Only 16 OECD countries have campaign spending limits for both parties and candidates. While such limits can prevent a spending race, challengers who generally need more funds to unseat an incumbent may be at a disadvantage in the other 18 countries.

Finally, a lack of independence or legal authority among some oversight institutions leaves big donors able to receive favours such as tax breaks, state subsidies, preferential access to public loans and procurement contracts.

The report recommends that:

- Countries should design sanctions against breaches of political finance regulations that are both proportionate and dissuasive.

- Countries should strike a balance between public and private political finance, bearing in mind that neither 100% private nor 100% public funding is desirable.

- Countries should aim for fuller disclosure with low thresholds, while taking privacy concerns of donors into consideration.

- Countries should focus on enforcing existing regulations, not adding new ones.

- Institutions responsible for enforcing political finance regulations should have a clear mandate, adequate legal power and the capacity to impose sanctions.

- Political finance regulations should focus on the whole cycle – the pre-campaign phase, the campaign period and the period after the elected official takes office.

You can read the full report here, including case studies of Brazil, Canada, Chile, Estonia, France, India, Korea, Mexico and the UK.