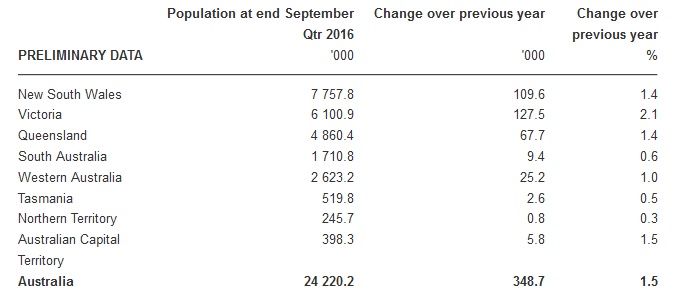

Australia’s population grew by 1.5 per cent during the year ending 30 June 2019, according to the latest figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

ABS Demography Director Beidar Cho said: “The population at 30 June 2019 was 25.4 million people, following an annual increase of 381,600 people.”

Natural increase accounted for 37.5 per cent of annual population growth, while net overseas migration accounted for the remaining 62.5 per cent.

There were 303,900 births and 160,600 deaths registered in Australia during the year ending 30 June 2019. Natural increase during this period was 143,300 people, an increase of 0.5 per cent from the previous year.

There were 536,000 overseas migration arrivals and 297,700 departures during the year ending 30 June 2019, resulting in net overseas migration of 238,300 people. Net overseas migration did not change compared to the previous year.

Annual population change

The preliminary estimated resident population of Australia at 30 June

2019 was 25,364,300 people. This is an increase of 381,600 people since

30 June 2018 and 75,600 people since 31 March 2019.

The annual population growth rate for the year ended 30 June 2019 was 1.5%.

Annual population growth rate (a)(b), Australia

(a) Annual growth rate calculated at the end of each quarter.

(b) All data to 30 June 2016 is final. Estimates thereafter are preliminary or revised.

Components of population change

The growth of Australia’s population is comprised of natural increase (births minus deaths) and net overseas migration (NOM).

The contribution to population growth for the year ended 30 June 2019

was higher from NOM (62.5%) than from natural increase (37.5%).

Components of annual population growth (a), Australia

(a) Annual components calculated at the end of each quarter.

Natural increase

The preliminary estimate of natural increase for the year ended 30 June 2019 was 143,300 people, an increase of 0.5%, or 700 people, compared with natural increase for the year ended 30 June 2018 (142,600 people).

Births

The preliminary estimate of births for the year ended 30 June 2019 (303,900 births) was lower by 700 births from the year ended 30 June 2018 (304,600 births).

Deaths

The preliminary estimate of deaths for the year ended 30 June 2019 (160,600 deaths) was lower by 1,400 deaths from the year ended 30 June 2018 (162,000 deaths).

Net overseas migration

For the year ended 30 June 2019, Australia’s preliminary net overseas migration estimate was 238,300 people. This was 100 people higher than the net overseas migration estimated for the year ended 30 June 2018 (238,200 people).

NOM arrivals increased by 1.6% (8,500 people) between the years ended 30 June 2018 (527,500 people) and 30 June 2019 (536,000 people).

NOM departures increased by 2.9% (8,400 people) between the years ended 30 June 2018 (289,300 people) and 30 June 2019 (297,700 people).

The preliminary NOM estimate for the June quarter 2019 (34,900 people) was 26.7% (12,700 people) lower than the June quarter 2018 (47,600 people).

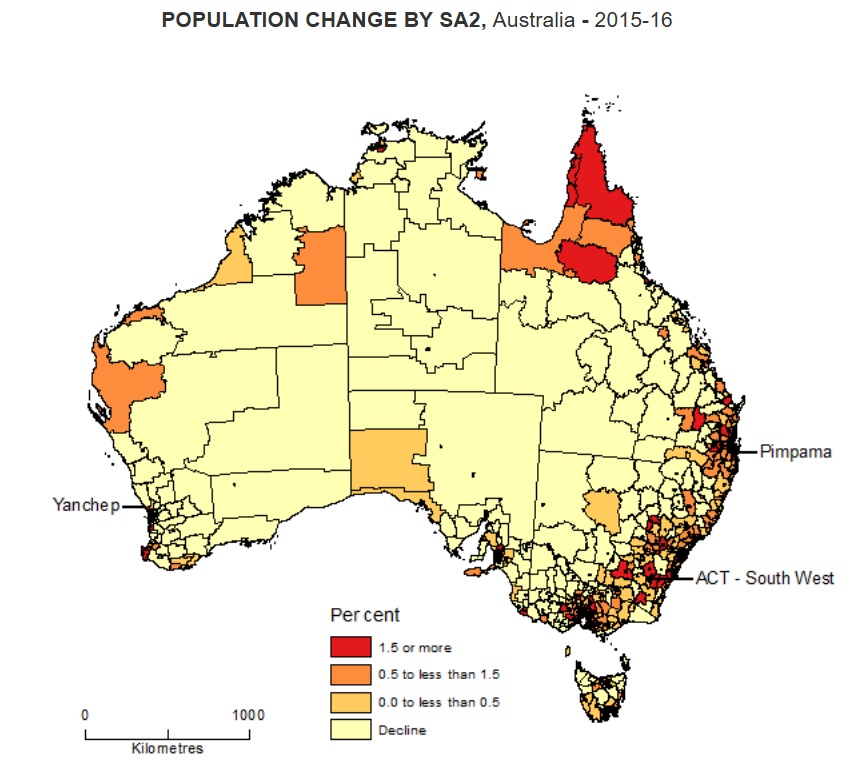

States and territories

At the state and territory level, population growth has three main components: natural increase, net overseas migration and net interstate migration (NIM).

Although majority of states and territories experienced positive population growth in the year ended 30 June 2019, the proportion that each of these components contributed to population growth varied between the states and territories.

For the year ended 30 June 2019, natural increase was the major contributor to population change in Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory. Net interstate migration loss was the largest component of population change in the Northern Territory. NOM was the major contributor to population change in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania.

NIM gains occurred in Victoria, Queensland and Tasmania. All other states and territories recorded net interstate migration losses.

Natural increase

Births

Compared with the previous year, the number of births registered for the year ended 30 June 2019 decreased in half of the states and territories.

The largest percentage decrease was in Western Australia at 2.7%. This was followed by Victoria (2.2%), The Northern Territory (1.9%) and Queensland (0.5%).

The largest increase was in Tasmania at 4.0%, followed by the Australian Capital Territory (2.1%), New South Wales (1.8%) and South Australia (1.6%).

For more information, see table 10.

Deaths

Compared with the previous year, the number of deaths registered for the year ended 30 June 2019 decreased in half of the states and territories.

Tasmania had the largest percentage decrease at 5.2%. This was followed by the Australian Capital Territory (4.7%), Queensland (2.7%) and New South Wales (1.0%).

Increases occurred in Western Australia at 2.1% followed by the Northern Territory (1.7%) and Victoria (0.1%). South Australia had no change.

For more information, see table 11.

Preliminary estimates of births and deaths are subject to fluctuations caused by lags or accumulations in the reporting of birth and death registrations (for more information see Explanatory Notes 10-11).

Net overseas migration

Compared with the previous year, NOM decreased the most in New South Wales (4,800 people), followed by Victoria (3,700 people), the Australian Capital Territory (1,500 people) and the Northern Territory (100 people).

The largest increase was in Queensland (5,200 people), followed by Western Australia (3,900 people), South Australia (1,100 people) and Tasmania (10 people). For more information, see table 13.

NOM arrivals

The number of NOM arrivals for the year ended 30 June 2019 increased in Tasmania (9.1%), Queensland (5.5%), South Australia (5.1%), Western Australia (3.9%), Victoria (1.8%) and the Northern Territory (1.2%).

The largest percentage decrease in NOM arrivals was in the Australian Capital Territory (11.4%), followed by New South Wales (0.7%). For more information, see table 13.

NOM departures

Compared with the previous year, the number of NOM departures for the year ended 30 June 2019 increased in Tasmania (19.7%), Victoria (9.0%), the Northern Territory (3.8%), the Australian Capital Territory (3.6%), New South Wales (3.4%) and South Australia (1.5%).

The largest percentage decrease was recorded in Western Australia at 6.7%, followed by Queensland (1.0%). For more information, see table 13.

Net interstate migration

In the year ended 30 June 2019, Victoria, Queensland and Tasmania had net interstate migration gains. Queensland had the highest net gain with 22,800 people. This was followed by Victoria (12,200 people) and Tasmania (2,000 people). Net losses from interstate migration were in New South Wales (22,100 people), Western Australia (6,500), the Northern Territory (4,400 people), South Australia (4,000 people) and the Australian Capital Territory (200 people). For more information.

Annual interstate migration – arrivals, departures and net