The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Go to the Walk The World Universe at https://walktheworld.com.au/

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Go to the Walk The World Universe at https://walktheworld.com.au/

Canada just announced a dial-down of their quantitative easing programme, but given the current trajectory of the virus, and the debt overhang, is a U-Turn even possible?

Go to the Walk The World Universe at https://walktheworld.com.au/

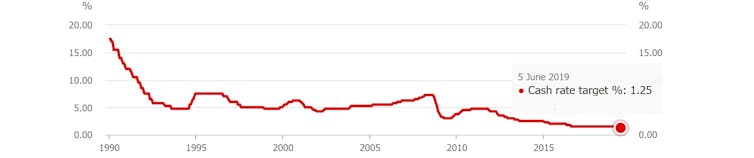

With its official cash rate now expected to fall below 1% to a new extraordinarily low close to zero, all sorts of people are saying that the Reserve Bank is in danger of “running out of ammunition.” Ammunition might be needed if, as during the last financial crisis, it needs to cut rates by several percentage points.

This view assumes that when the cash rate hits zero there is nothing more the Reserve Bank can do.

The view is not only wrong, it is also dangerous, because if taken seriously it would mean that all of the next rounds of stimulus would have to be come from fiscal (spending and tax) policy, even though fiscal policy is probably ineffective long-term, its effects being neutralised by a floating exchange rate.

The experience of the United States shows that Australia’s Reserve Bank could quite easily take measures that would have the same effect as cutting its cash rate a further 2.5 percentage points – that is: 2.5 percentage points below zero.

Reserve Bank cash rate since 1990

In a report released on Tuesday by the University of Sydney’s United States Studies Centre, I document the successes and failures of the US approach to so-called “quantitative easing” (QE) between 2009 and 2014.

It demonstrates that it is always possible to change the instrument of monetary policy from changes in the official interest rate to changes in other interest rates by buying and holding other financial instruments such as long-term government and corporate bonds.

The more aggressively the Reserve Bank buys those bonds from private sector owners, the lower the long-term interest rates that are needed to place bonds and the more former owners whose hands are filled with cash that they have to make use of.

In the US the Federal Reserve also used “forward guidance” about the likely future path of the US Federal funds rate to convince markets the rate would be kept low for an extended period.

It is unclear which mechanism was the most powerful, or whether the Fed even needed to buy bonds in order to make forward guidance work. However in a stressed economic environment, it is worth trying both.

As it comes to be believed that interest rates will stay low for an extended period, the exchange rate will fall, making it easier for Australian corporates to borrow from overseas and to export and compete with imports.

The consensus of the academic literature is that QE cut long-term interest rates by around one percentage point and had economic effects equivalent to cutting the US Federal fund rate by a further 2.5 percentage points after it approached zero.

Based on US estimates, Australia’s Reserve Bank would need to purchase assets equal to around 1.5% of Australia’s Gross Domestic Product to achieve the equivalent of a 0.25 percentage point reduction in the official cash rate. That’s around A$30 billion.

With over A$780 billion in long-term government (Commonwealth and state) securities on issue, there’s enough to accommodate a very large program of Reserve Bank buying, and the bank could also follow the example of the Fed and expand the scope of purchases to include non-government securities, including residential mortgage-backed securities.

It could also learn from US mistakes. The Fed was slow to cut its official interest rate to near zero and slow to embark on QE in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Its first attempt was limited in size and duration. Its success in using QE to stimulate the economy should be viewed as the lower bound of what’s possible.

It often suggested (although it is by no means certain) that monetary policy becomes less effective when interest rates get very low, but this isn’t necessarily an argument to use monetary policy less. It could just as easily be an argument to use it more.

Because there is no in-principle limit to how much QE a central bank can do, it is always possible to do more and succeed in lifting inflation rate and spending.

Fiscal policy may well be even less effective. To the extent that it succeeds, it is likely to push up the Australian dollar, making Australian businesses less competitive.

US economist Scott Sumner believes the extra bang for the buck from government spending or tax cuts (known as the multiplier) is close to zero.

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe this month appealed for help from the government itself, asking in particular for extra spending on infrastructure and measures to raise productivity growth.

He is correct in identifying the contribution other policies can make to driving economic growth. No one seriously thinks Reserve Bank monetary policy can or should substitute for productivity growth.

But it is a good, perhaps a very good, substitute for government spending that does not contribute to productivity growth.

In the paper I address several myths about QE. One is that it is “printing money”. It no more prints money than does conventional monetary policy. It pushes money into private sector hands by adjusting interest rates, albeit a different set of rates.

Another myth is that it promotes inequality by helping the rich to get richer.

It is a widely believed myth. Former Coalition treasurer Joe Hockey told the British Institute of Economic Affairs in 2014 that:

Loose monetary policy actually helps the rich to get richer. Why? Because we’ve seen rising asset values. Wealthier people hold the assets.

But it widens inequality no more than conventional monetary policy, and may not widen it at all if it is successful in maintaining sustainable economic growth.

A third myth is that it leads to excessive inflation or socialism.

In the US it has in fact been associated with some of the lowest inflation since the second world war. These days central banks are more likely to err on the side of creating too little inflation than too much.

Some have argued that QE in the US is to blame for the rise of left-wing populists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and “millennial socialism”. But it is probably truer to say that their grievances grew out of too tight rather than too lose monetary policy.

QE has been road tested. We’ve little to fear from it, just as we have had little to fear from conventional monetary policy.

Author: Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

We review recent changes in central bank policies which will involve another bout of quantitative easing, and the impact on the saver community – a sector which silently are being taken to the cleaners. Why no fuss?

Eurozone (EZ) GDP growth now looks likely to slow to just 1% this year according to a report published by Fitch Ratings‘ Economics team. The deterioration in growth prospects and declining inflation expectations will prompt the ECB to consider restarting asset purchases.

Economic activity data from the EZ has deteriorated more sharply than other parts of the world in recent months and has delivered the biggest negative surprise relative to market and Fitch’s own expectations.

“While numerous transitory factors are partly to blame, these cannot explain the breadth and depth of the slowdown. Rather, we believe that the slowdown has been primarily the result of deterioration in the external environment as net trade turned from a tailwind to a headwind,” said Fitch’s Chief Economist, Brian Coulton.

The domestic slowdown in China has, we believe, played a particularly important role here. Germany’s greater trade openness and larger exposure to China leave the largest European economy’s expansion more vulnerable to China’s domestic cycle and import demand. This is underlined by Germany having seen the biggest deterioration in activity data among the EZ economies – despite a healthy domestic economy with few of the imbalances that typically spark an abrupt downturn in domestic demand. Furthermore, the deterioration in manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) since last summer has been greatest in countries with a large auto export sector, dragged down by the first decline in global car sales since 2009 and the first fall in vehicle sales in China for several decades.

The weakening in EZ external indicators has not been matched in the domestic economy. Labour market performance remains strong supporting household income growth, monetary policy remains supportive, bank lending conditions are easy and credit to households and businesses continues to grow. Only in Italy have we seen evidence of private sector borrowers reporting somewhat tighter credit availability. Fiscal policy is also being eased in the EZ and should be supportive of growth in 2019. Private sector debt ratios have improved significantly since 2012 in Italy, Spain and Germany.

EZ growth should recover through the course of 2019 as the policy response in China helps to stabilise its economy from the middle of the year, one-off impediments to growth in Germany unwind, and EZ macro policy is eased. However, early indications for 1Q19 and the profile of our China forecast mean that there will not be much of a pick-up in EZ quarterly growth before 2H19.

This suggests that EZ growth in 2019 is likely to be around 1% compared with our December 2018 GEO forecast of 1.7%, a substantial cut. Both Germany and Italy will see similar revisions, with 2019 GDP growth now forecast at around 1% and 0.3% respectively. Even with this lower forecast, downside risks remain from an escalation in global trade tensions, a deeper slowdown in China, a disorderly no-deal Brexit or increased uncertainty related to domestic political tensions.

The sharp deterioration in growth prospects and falling inflation expectations are likely to result in renewed monetary stimulus measures from the ECB.

“We had already been expecting the ECB to delay the start of its policy normalisation -both interest rates and balance sheet reduction – but we now believe it will seriously consider restarting QE asset purchases relatively soon,” added Robert Sierra, Director in Fitch’s Economics team..

We also foresee the ECB announcing a one- to two-year long-term refinancing operation (LTRO) in March to replace the existing TLTRO2 programme, which matures from June 2020. The rationale for a new targeted LTRO (TLTRO) is less convincing in light of improved conditions in the banking sector, but the ECB will want to avoid an unwarranted tightening in credit conditions by abruptly withdrawing liquidity facilities.

Agustín Carstens, General Manager, Bank for International Settlements spoke in Beijing recently and discussed the challenges going forward for central banks, as the monetary policy normalistion (following a decade of ultra-low interest rates, QE and the like), are unwound. He admits that the starting point of the ongoing normalisation is unprecedented, and there are extreme uncertainties involved.

Household debt is high and rising in many advanced and emerging market economies. Quantitative easing has been a “volatility stabiliser” in financial markets and when it is removed or reversed, it is not clear how the market will react. We are in uncharted territory! Yet, monetary policy normalisation is essential for rebuilding policy space, creating room for countercyclical policy.

Monetary policy normalisation in the major advanced economies is making uneven progress, reflecting different stages of recovery from the GFC. The Federal Reserve has begun unwinding its asset holdings by capping reinvestments and has increased policy rates. The ECB has scaled back its large-scale asset purchases, with a likely halt of net purchases by end-year. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan is continuing with its purchases and has not communicated any plan for exiting.

The ongoing unwinding of accommodative monetary policy in core advanced economies is a welcome step. It is a sign of success as economies have been brought back to growth and inflation rates back towards target levels. Monetary policy normalisation is essential for rebuilding policy space, creating room for countercyclical policy. Moreover, it can help restrain debt accumulation and reduce the risk of financial vulnerabilities emerging.

But there are also significant challenges. The starting point of the ongoing normalisation is unprecedented, and there are extreme uncertainties involved. The path ahead for central banks is quite narrow, with pitfalls on either side. Central banks will need to strike and maintain a delicate balance between competing considerations. This includes, in particular, the challenge of achieving their inflation objectives while avoiding the risk of encouraging the build-up of financial vulnerabilities.

Central banks have prepared and implemented normalisation steps very carefully. Policy normalisation has been very gradual and highly predictable. Central banks have placed great emphasis on telegraphing their policy steps through extensive use of forward guidance. As a consequence, major financial and economic ructions have so far been avoided. In this regard, the increased resilience of the financial sector as a consequence of the wide regulatory and supervisory reforms undertaken since 2009 has also helped.

That said, there are still plenty of risks out there.

First, central banks are not in control of the entire yield curve and of the behaviour of risk premia. Investor sentiment and expectations are key factors determining these variables. An abrupt repricing in financial markets may prompt an outsize revision of the expected level of risk-free interest rates or a decompression in risk premia. Such a snapback could be amplified by market dynamics and have adverse macroeconomic consequences. It could also be accompanied by sudden sharp exchange rate fluctuations and spill across borders, with broader repercussions globally.

Second, many intermediaries are in uncharted waters. Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have grown faster than actively managed mutual funds over the past decade, and needless to say, they have brought very important benefits to bond markets, among other factors, by enhancing the depth of such markets and making possible new ways of financing for many sovereigns and corporations. ETFs are especially popular among equity investors, but they have also gained importance among bond investors.They have attracted investors because they charge lower fees than traditional mutual funds, which has proved to be an important advantage in the ultra-low interest rate environment. Moreover, they promise liquidity on an intraday basis, hence more immediately than mutual funds, which provide it only daily.

Such promise of intraday liquidity is, however, a double-edged sword. As soon as ETF investors are confronted with negative news or observe an unexpected fall in the underlying asset price, they can run – that is, sell their ETF shares immediately – adding to the downward pressure on market prices. As equity markets become choppier, we will need to be on the look-out for ETFs possibly accentuating the volatility of the underlying asset market.

Currently, bond ETFs are still small compared with bond mutual funds in terms of their assets under management. However, as the market share of ETFs increases, their impact on market price dynamics will also increase. Moreover, they have yet to be tested in periods of high interest rates.

More generally, investors may face unforeseen risks – in particular, unforeseen dry-ups in liquidity. As I mentioned earlier, the growing size of the asset management industry may have increased the risk of liquidity illusion: market liquidity seems to be ample in normal times, but dries up quickly during market stress. Asset managers and institutional investors do not have strong incentives to play a market-making role when asset prices fall due to large order imbalances. Moreover, precisely when asset prices fall, asset managers often face redemptions by investors. This is especially true for bond funds investing in relatively illiquid corporate or EME bonds. Therefore, when market sentiment shifts adversely, investors may find it more difficult than in the past to liquidate bond holdings.Central banks’ asset purchase programmes may also have contributed to liquidity illusion in some bond markets. Such programmes have led to portfolio rebalancing by investors from safe government debt towards riskier bonds, including EME bond markets, making them look more liquid. However, such liquidity may disappear in the event of market turbulence. Also, as advanced economy central banks unwind their asset purchase programmes and increase policy rates, investors may choose to rebalance from riskier bonds back to safe government bonds. This can widen spreads of corporate and EME bonds.

Moreover, asset managers’ investment strategies can collectively increase financial market volatility. A key source of risk here is asset managers’ “herding” in illiquid bond markets. Fund managers often claim that their performance is evaluated over horizons as long as three to five years. Nevertheless, they tend to have a strong aversion to underperforming over short periods against industry peers. This can lead to increased risk-taking and highly correlated investment strategies across asset managers. For example, recent BIS research shows that EME bond fund investors tend to redeem funds at the same time. Moreover, the fund managers of the so-called actively managed EME bond funds are found to closely follow a small number of benchmarks (a practice known as “benchmark hugging”).

Third, the fundamentals of many economies are not what they should be while at the same time there seems to be less political appetite for prudent macro policies. High and rising sovereign debt relative to GDP in many advanced economies has increased the sensitivity of investors to the perceived ability and willingness of governments to ensure debt sustainability. Sovereign debt in EMEs is considerably lower than in advanced economies on average, but corporate leverage has continued to rise and has reached record levels in many EMEs.

Also, household debt is high and rising in many advanced and emerging market economies. In addition, a large amount of EME foreign currency debt matures over the next few years, and large current account and fiscal deficits in some EMEs could induce global investors to take a more cautious stance. Tightening global financial conditions and EME currency depreciation may increase the sensitivity of investors to these vulnerabilities.

Fourth, other factors may augment the spillover effects from unwinding unconventional monetary policy. Expansionary fiscal policy in some core advanced economies may further push up interest rates, by increasing government bond supply and aggregate demand in already-overheating economies. Trade tensions have started to darken the growth prospects and balance of payments outlook of many countries. Such tensions also have repercussions on exchange rates and corporate debt sustainability. Heightened geopolitical risks should not be ignored either. The sharp corrections in advanced economy and EME equity markets alike in October 2018 are generally attributed to both aggravating trade tensions and geopolitical risks.

Fifth, there is much uncertainty about how investors will react to monetary policy normalisation. Quantitative easing has been a “volatility stabiliser” in financial markets. Thus, when it is removed or reversed, it is not clear how the market will react. Market segments of particular concern are high-yield bonds and EME corporate bonds. As I pointed out a moment ago, liquidity tends to dry up more easily in these markets. Knowing this, asset managers may try to rebalance their portfolios by deleveraging more liquid surrogates first, which creates an avenue for contagion to other markets.

“Tourist investors” are another source of concern. For example, in contrast to “dedicated” bond funds, which follow specific benchmarks relatively closely, “crossover” funds have benchmarks but deviate from them and cross over to riskier asset classes such as EME bonds and high-yield corporate bonds in search of yield. Crossover funds are not new, but they have gained prominence recently. They include high-yield, high-risk bonds in their portfolio by arguing that the extra return from such investments is high enough to compensate for their risk. They are likely to underprice risks when markets are calm, but overprice risks when markets become volatile. They are, indeed, very responsive to interest rate and exchange rate surprises and tend to pull out suddenly from risky investments.

Finally, significant allocations by global asset managers to domestic currency bond markets, in particular to EME local currency sovereign bonds, have generated new challenges. After the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98, many emerging Asian economies made concerted efforts to develop their local currency bond markets. This was a welcome development, overcoming “original sin”, a term coined by Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann in 1999 for the inability of developing countries to borrow in their domestic currency. By relying on long-term local currency bonds instead of short-term foreign currency loans, many Asian EME borrowers were able to avoid currency mismatch and reduce rollover risk. In addition, over the past several years, the average maturity of EME local currency bonds has increased overall.

However, as the share of foreign investment in EME local currency bond markets has increased, currency and rollover risks have been replaced by duration risk. The effective duration of an investment measures the sensitivity of the investment return to the change in the bond yield. Recent BIS research shows that EME local currency bond yields tend to increase in tandem with domestic currency depreciation. This can make returns of EME local currency bond investors, whose investment performance is measured in the US dollar (or the euro), extremely volatile. As an analogy, incorporating exchange rate consideration is similar to viewing temperatures with and without a wind chill factor.

This suggests that the exchange rate response to capital flows might not stabilise economies as textbooks predict: it might instead lead to procyclical non-linear adjustments. Exchange rate changes can drive capital in- and outflows via the so called risk-taking channel of exchange rates.

The core mechanism of the risk-taking channel works as follows. In the presence of currency mismatch, a weaker dollar flatters the balance sheet of the EME’s dollar borrowers. This induces creditors (either global banks or global bond investors) to extend more credit. As a consequence, a weaker dollar goes hand in hand with reduced tail risks and increased EME borrowing. However, when the dollar strengthens, these relationships go into reverse.

Policy implications

Monetary policy normalisation by major advanced economies, escalating trade tensions, heightened geopolitical risks and new forms of financial intermediation all pose challenges going forward for both advanced and emerging market economies. How can policymakers rise to these challenges?

Inadequate growth-enhancing structural policies have been a major deficiency over the past years. Such policies would facilitate the treatment of overindebtedness. In contrast to expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, which boost both debt and output, growth-enhancing structural reforms would primarily boost output, thus reducing debt burdens relative to incomes. Moreover, by improving the supply side of the economy, they would contain inflationary pressures. And, if sufficiently broad in scope, they would have positive distributional effects, reducing income inequality.

Advanced economies should be mindful of spillovers, also because they can mutate into spillbacks. During phases in which interest rates remain low in the main international funding currencies, especially the US dollar, EMEs tend to benefit from easy financial conditions. These effects then play out in reverse once interest rates rise. A reversal could occur, for instance, if bond yields snapped back in core advanced economies, and especially if this went hand in hand with US dollar appreciation. A clear case in point is the change in financial conditions experienced by EMEs since the US dollar started appreciating in the first quarter of 2018.

Global spillovers can also have implications for the core economies. The collective size of the countries exposed to the spillovers suggests that what happens there could also have significant financial and macroeconomic effects in the originating economies. At a minimum, such spillbacks argue for enlightened self-interest in the core economies, consistent with domestic mandates. This is an additional policy dimension that complicates the calibration of the normalisation and that deserves close attention.

Financial reforms should be fully implemented. If enforced in a timely and consistent manner, these reforms will contribute to a much stronger banking system. Indeed, the Basel Committee’s Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme has found that its members have put in place most of the major elements of Basel III. But implementation delays remain. It is important to attain full, timely and consistent implementation of all the rules. This would improve the resilience of banks and the banking system. It is also necessary for attaining a level playing field and limiting the room for regulatory arbitrage.

For EMEs, keeping one’s house in order is paramount because there is no room for poor fundamentals during tightening global financial conditions. EMEs may nevertheless face capital outflows, and their currencies may depreciate abruptly, which would trigger further capital outflows. In such instances, EME authorities must be prepared to respond forcefully. They should consider combining interest rate adjustments with other policy options such as FX intervention. And they should consider using the IMF’s contingent lending programmes.

At the same time, EMEs should not disregard non-orthodox policies to deal with stock adjustment. If a large amount of foreign capital has flowed into domestic markets and threatens to flow out quickly, the central bank can use its balance sheet to stabilise markets. As an example, the Bank of Mexico has in the past swapped long-term securities for short-term securities via auctions. This was done because such long-term instruments were not in the hands of strong investors, and there was market demand for short-term securities. This policy stabilised conditions in peso-denominated bond markets.

Finally, policymakers need to better understand asset managers’ behaviour in stress scenarios and to develop appropriate policy responses. One key question for policymakers is how to dispel liquidity illusion and to support robust market liquidity. Market-makers, asset managers and other investors would need to take steps to strengthen their liquidity risk management. Policymakers can also provide them with incentives to maintain robust liquidity during normal times to weather liquidity strains in bad times – for example, by encouraging regular liquidity stress tests.

The combined net asset purchases of the four central banks (CB) that engaged in quantitative easing (QE) will turn negative in 2019, one year earlier than Fitch Ratings previously estimated. This underscores the shift in global monetary conditions that is underway – as strong global growth continues and labour markets tighten – and could portend an increase in financial market volatility.

The four “QE” CBs – i.e. the Fed, European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Japan (BOJ) and Bank of England (BOE) – made net asset purchases equivalent to around USD1,200 bilion per annum on average over 2009 to 2017. This is set to slow significantly this year to around USD500 billion as the Fed’s balance sheet shrinks, the BOJ engages in de facto tapering and ECB purchases are phased out by year-end. More significantly, combined net asset purchases are expected to turn negative next year as the decline in the Fed’s balance sheet will be larger in absolute terms than ongoing net purchases by the BOJ.

This shift to global quantitative tightening (QT) is now expected to happen a year earlier than previously estimated (see “Quantitative Easing – The Beginning of the End” – Fitch, November 2017) reflecting a downwardly revised forecast for BOJ purchases in 2019. The decline in combined CB asset holdings is expected to be around USD200 billion in both 2019 and 2020. The peak in QT is expected to occur in 2021 as the ECB and BOE start to unwind purchases, while the Fed is still in the process of normalising its balance sheet, albeit at a somewhat slower pace.

The impact of such a large turnaround in CB purchases on global financial markets is likely to be significant, despite it being widely anticipated and despite the smooth progress seen with the Fed’s balance sheet reduction since last October.

There is very strong empirical evidence to suggest that CB purchases have reduced bond yields, implying upward pressure on yields as purchases are unwound. The limited impact on US bond yields from the decline in Fed holdings since October 2017 may partly reflect international spill-overs from ongoing ECB and BOJ purchases, as existing holders of Japanese and eurozone government bonds have been forced to look for alternative ‘safe assets’ after selling bonds to the BOJ and ECB.

But private sector investors will be called upon to absorb a much greater net supply of government debt in the coming years as CB reduce holdings and government financing needs persist in Europe and Japan and rise sharply in the US.

CB purchases have likely been a factor dampening financial market volatility by providing a large and steady ‘bid’ for fixed-income assets and a bid that is not sensitive to market price fluctuations. In this context it is notable that financial market volatility has risen in 2018 as combined CB net purchases have slowed.