We look at the latest credit stats from the RBA and APRA. The credit impulse is slowing. Its at the slowest rate since 1974. So what does that really mean?

Tag: RBA

Non Bank Home Lending Rising

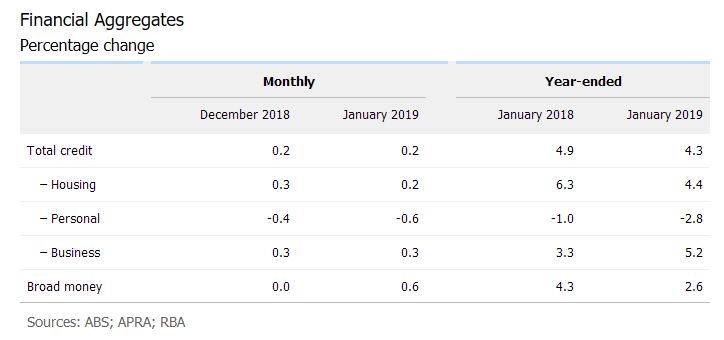

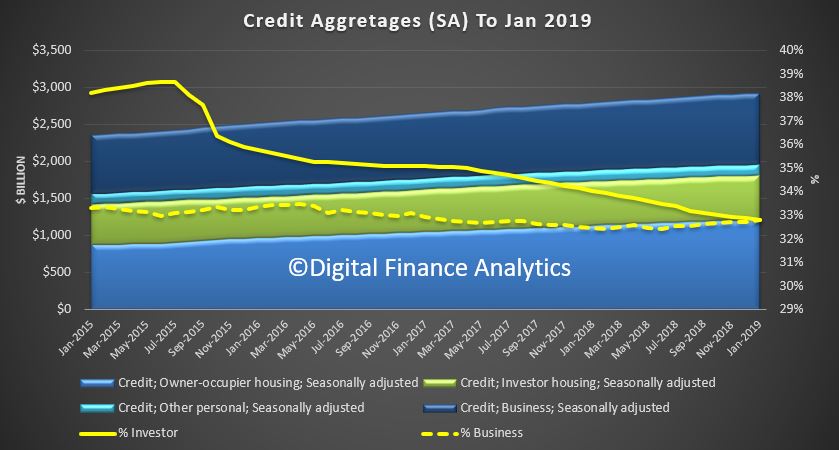

The RBA released their credit aggregates to end January 2019 today, and the data confirms that lending growth continues to slow across home lending and personal credit.

We will get to the detail shortly, but I want first to head to a comparison between the APRA data for the banks, also released today, and the total credit from the RBA.

The gap between the two relates to the non-bank sector, and the fact is, despite all the funnies in the numbers, lending from the non-bank credit sector is booming. Owner occupied non-bank lending is growing at an annualised rate of 17.2% and lending for investment housing is 4%. Both well above the bank sector. This is unsurprising, given the different funding arrangements, and restrictions between the banks and non-banks. Of course both have responsible lending obligations, but evidence suggests non-banks are more willing to lend, at a price. APRA sort of has responsibility for the non-bank sector, but do not seem to be doing much to stem the tide.

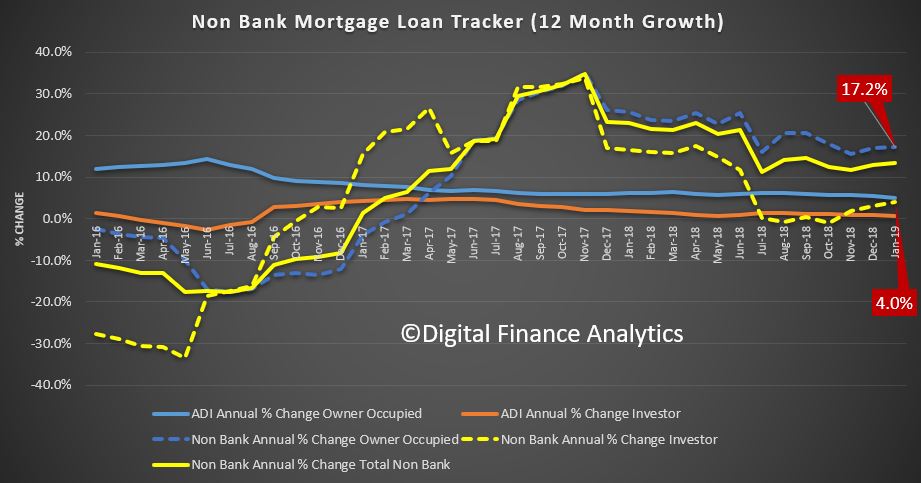

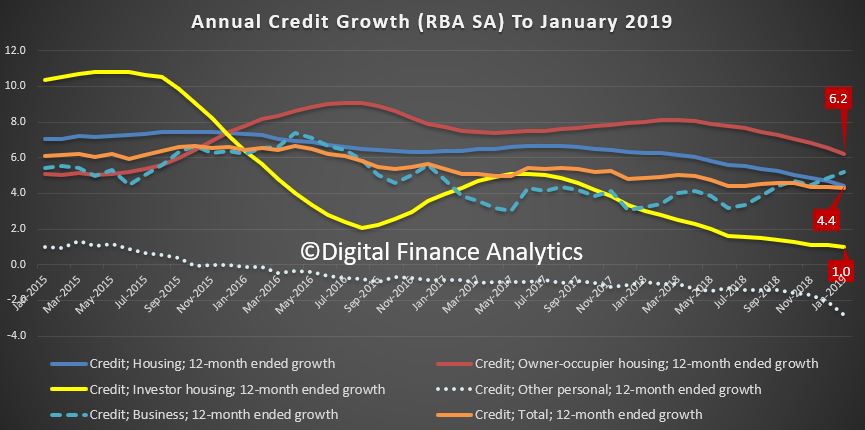

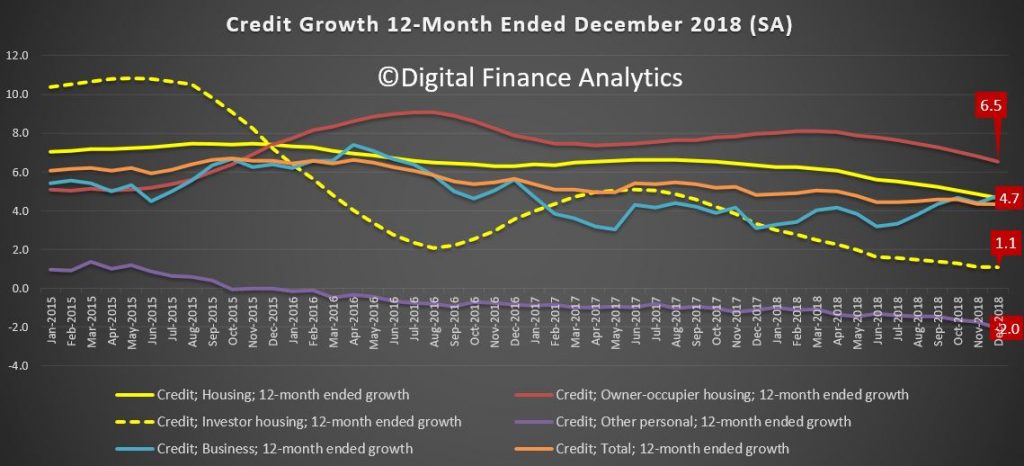

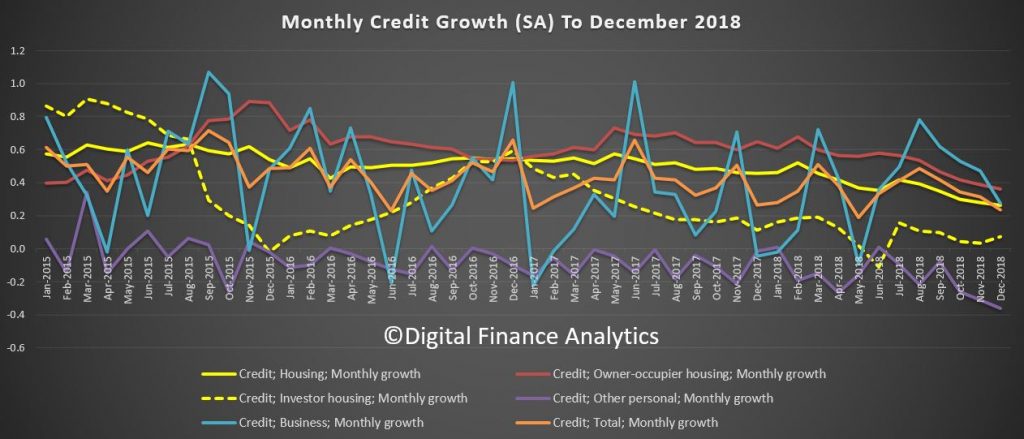

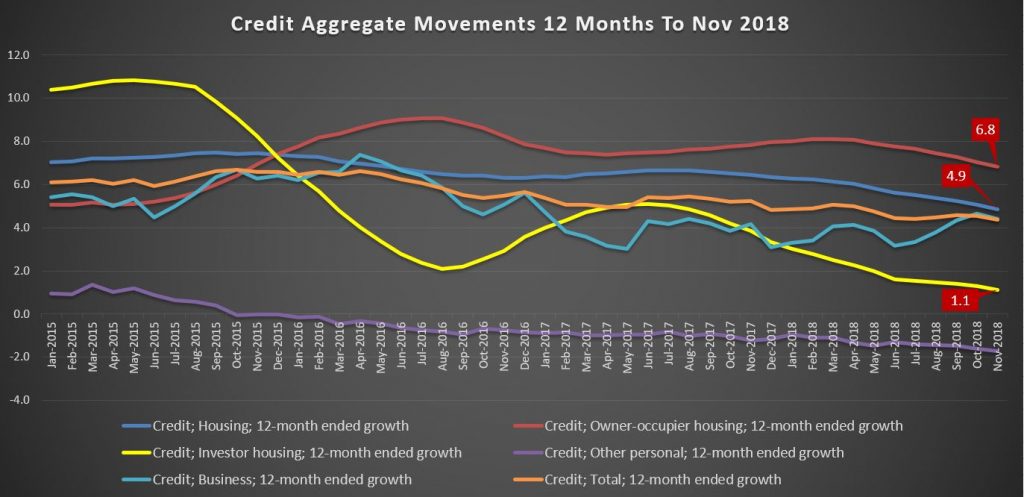

Meantime, the RBA lending aggregates shows that annual owner home lending now stands at 6.2%, investment lending at 1% and overall credit growth is 4.4%. There was a considerable drop off in personal credit, and a rise in business lending.

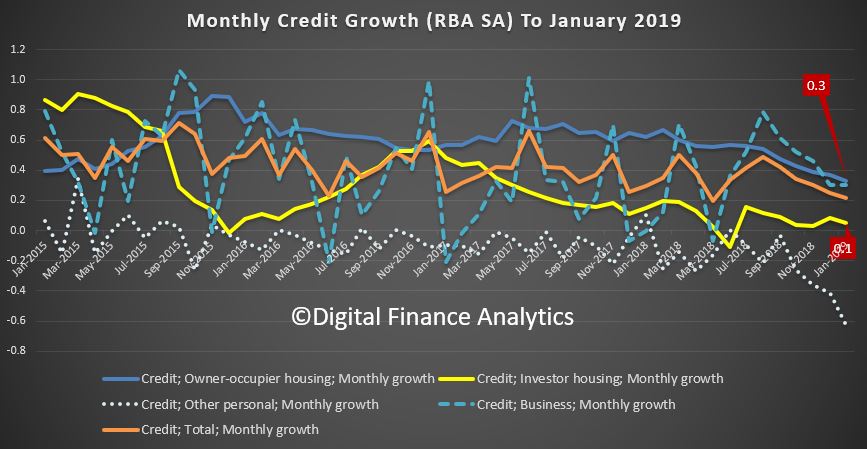

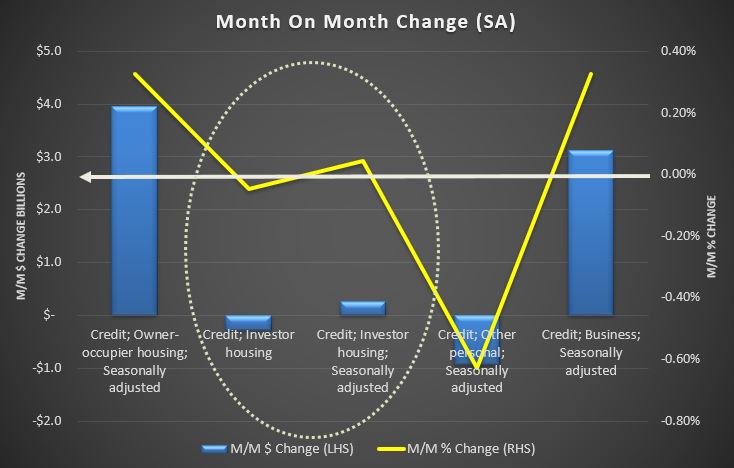

The monthly trends are more noisy, as expected.

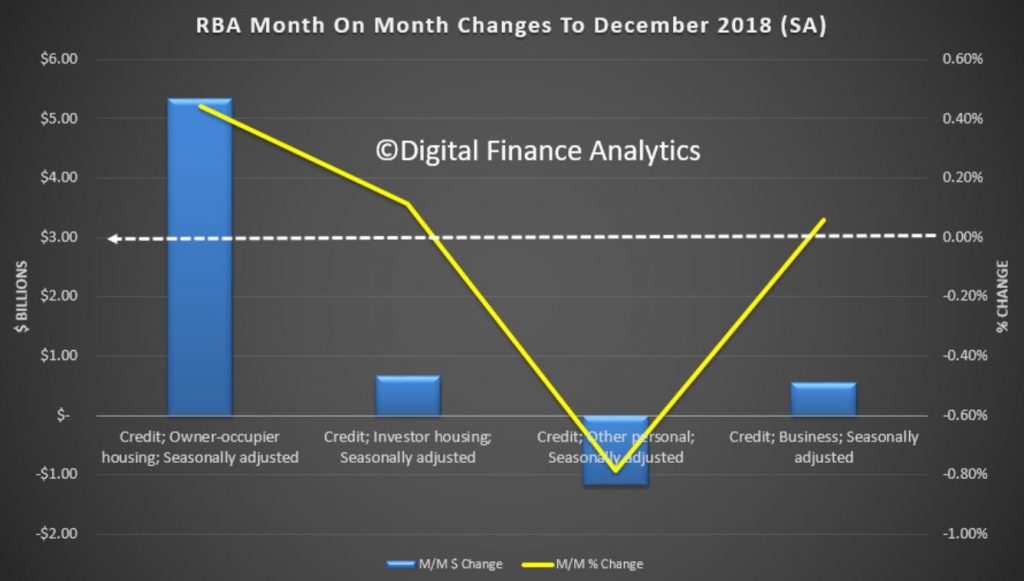

Turning to the credit stock, and using the seasonally adjusted figures, we see that overall credit still advanced. Total loans for owner occupation rose by $4 billion dollars to $1.22 trillion dollars, up 0.33% while loans for investors rose $0.3 billion seasonally adjusted to $594.6 billion dollars, up just 0.04%. Investment loans were 32.8% of the total, down slightly from last month.

Business credit rose by $3.1 billion to $956 billion, up 0.33% and comprised 32.8% of all lending, up a little from last month.

Personal credit fell by $0.9 billion dollars to $147.5 billion, down 1.15%,

Its also worth noting the seasonally adjusted figures overstates the investment lending by a net $0.6 billion dollars.

To me the slowing credit impulse is clear, as is the worrying rise in non-bank lending. Adopt the brace position!

RBA Minutes, Long But Little Sense

The RBA released their minutes today, probably the longest ever! But I am not sure they see the obvious. Slowing consumption, lower growth = slowing economy. Wages growth later won’t save the day!

International Economic Conditions

Members commenced their discussion of the global economy by noting that growth in Australia’s major trading partners had been above trend, despite moderating in the second half of 2018. Growth in major trading partners was forecast to be around trend in 2019 and 2020. However, the downside risks to the global outlook had increased in the preceding few months. Members noted that it was difficult to predict the effectiveness of recent policy measures in China and how the authorities would balance their objectives of supporting growth and containing financial risks. Trade tensions and signs of slowing domestic demand had also increased the risks to the outlook for China. More broadly, trade tensions remained a material risk to the global growth outlook.

US exports to China and Chinese exports to the United States had fallen sharply in late 2018 as a result of earlier tariff increases. There had been ongoing speculation that the United States might impose tariffs on automotive imports, which would affect imports from Germany and Japan. Some economies, particularly in the east Asian region, had been affected by the trade tensions because they provide inputs to Chinese exports as part of global supply chains. A number of economies had also faced a moderation in export growth because Chinese domestic demand had slowed. However, members noted that there had also been reports of firms accelerating existing plans to shift production from China to other low-cost producers in the east Asian region.

Labour markets had tightened further in most advanced economies and wages growth had increased. Core inflation had picked up to be close to target in some advanced economies, but remained low in others. Headline inflation had declined towards the end of 2018 because oil prices had fallen by almost 30 per cent from their peak in October.

GDP growth in the United States had remained strong over 2018. Fiscal stimulus and strong employment growth had supported consumption growth. The labour market had continued to tighten in early 2019 and wages growth had picked up. However, the outlook for investment had softened. Some measures of business and consumer confidence had fallen sharply in January. However, members noted that it was difficult to determine whether this reflected uncertainty associated with volatility in financial markets or a genuine deterioration in the circumstances facing businesses and consumers.

GDP growth in Japan was expected to recover after the sharp slowing in the September quarter, which had mainly reflected disruptions from natural disasters. Growth in consumption had been supported by a strong labour market and a pick-up in wages growth. Members noted that consumption would receive a short-term boost as consumers brought forward spending ahead of an increase in the consumption tax in October. Recent data suggested that business conditions in Japan had also remained positive. By contrast, growth in output in the euro area had slowed over 2018, reflecting a combination of weaker external demand, especially from China, and some localised factors that could have persistent effects, particularly if they were not resolved quickly. Investment intentions and surveyed business conditions had fallen recently in the euro area.

GDP growth in China had slowed in 2018, as had been expected given the earlier tightening in financial conditions. However, there were signs that underlying momentum in the Chinese economy had slowed by more than suggested by the GDP data. The authorities had responded with further targeted policy measures. Many of these measures were aimed at encouraging spending on infrastructure, which had led to a lift in growth in public infrastructure investment and an upgrade to the outlook for steel demand. In India, crude steel production had remained high in 2018, despite an easing in GDP growth overall.

The improved outlook for steel demand and stockpiling ahead of the Chinese New Year had supported prices for iron ore at the end of 2018, and earlier increases in oil prices had boosted liquefied natural gas (LNG) prices. As a result, Australia’s terms of trade were expected to have increased in the December quarter. Iron ore prices had increased further in 2019, following the collapse of a tailings dam at an iron ore mine in Brazil and the subsequent closure of a number of other similar mines. Members observed that iron ore prices could remain high for some time, but prices were still expected to decline over the medium term. Looking ahead, the effect of higher iron ore prices on the terms of trade was expected to be offset by the effect of lower prices for LNG, as the decline in oil prices since October gradually feeds through.

Domestic Economic Conditions

The September quarter national accounts had been released the day after the December meeting. Members noted that growth in real GDP of 0.3 per cent in the quarter and 2.8 per cent over the year had been noticeably below expectations. There had also been downward revisions to GDP growth in previous quarters, which had subtracted around ¼ percentage point from the year-ended growth rate. Taking account of this and other information, the Bank had revised down its forecast for growth in the Australian economy by around ¼ percentage point for both 2019 and 2020. This primarily reflected a modest downgrading of the outlook for household consumption and residential construction. The outlook had also become more uncertain over the preceding few months.

Growth in GDP was expected to be around 3 per cent over 2019, supported by accommodative monetary policy and ongoing strength in public spending and business investment. Further gradual tightening in the labour market was expected to support growth in household income and consequently growth in household consumption. GDP growth was expected to moderate to 2¾ per cent over 2020 because LNG output was expected to reach targeted levels of production and would therefore no longer materially add to growth. Dwelling investment was also expected to decline more sharply than previously expected, consistent with the decline in residential building approvals and the fall in housing prices.

Growth in consumption had slowed to 2½ per cent over the year to the September quarter. Revisions to previously published data made it difficult to assess the underlying momentum of consumption over the preceding year. On balance, the slower reported growth in consumption, together with subdued growth in retail sales in the December quarter and the likely effect of lower housing prices and reduced housing market activity on consumption, warranted a downward revision to the outlook for consumption. As a result, year-ended growth in consumption was expected to pick up only a little over the forecast period. Members noted that uncertainty about the recent momentum of consumption and factors affecting households’ future consumption decisions remained a key risk for the domestic economic outlook.

Dwelling investment was likely to have been close to its peak in the second half of 2018. Although there was still a large pipeline of residential work to be done and few signs that projects already under way were being cancelled, it had become more difficult for new apartment projects to obtain finance, and building approvals were the lowest they had been for five years. As a result, dwelling investment was expected to remain at a high level in the near term, but then to decline faster than previously expected. Members noted the uncertainty about the extent and speed of the downturn in the dwelling investment cycle.

Non-mining investment had been flat in the September quarter. Non-residential construction had declined, but the pipeline of work yet to be done had remained relatively high, suggesting that non-residential construction would recover in coming quarters. Investment in machinery & equipment and computer software had grown solidly in the September quarter. A reasonably positive outlook for investment was supported by continued growth in corporate profits and accommodative financial conditions for larger firms, although conditions for smaller firms had been more constrained. While information from liaison implied that the economy had reasonable momentum around the turn of the year, surveyed business conditions had declined to around their long-run average. A large pipeline of projects was expected to support growth in public investment over the following year.

Mining investment had fallen in the September quarter. Liaison had suggested that very little additional spending was needed to bring the remaining LNG projects on line. Mining investment was expected to increase over the forecast period as mining firms invest to maintain production; this outlook was supported by mining firms’ profitability having remained strong. Members noted that the declines in mining investment that had weighed on growth for the previous six years were close to an end, and instead mining investment was expected to make a small contribution to output growth in the forecast period. Recent trade data suggested that supply disruptions had continued to affect resource exports in the December quarter.

Farm output had fallen by 8 per cent over the year to the September quarter, subtracting around ¼ percentage point from year-ended GDP growth. Members noted that the outlook for the farm sector continued to depend on the timing and magnitude of rainfall; drier-than-average conditions in key farming areas were expected to continue in the near term. Recent trade data suggested that rural exports had fallen in the December quarter, and the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences had revised down its forecast for farm production in 2018/19.

Members noted the continued improvement in conditions in the labour market and that the labour market data had been stronger than other data on economic activity. Employment had continued to grow faster than the working-age population in the December quarter, with most of this growth in full-time employment. Forward-looking indicators had been consistent with above-average employment growth over the first half of 2019. The unemployment rate had declined to 5 per cent, which was the lowest rate since 2011 and lower than had been expected a year earlier. Labour market conditions had been particularly strong in New South Wales and Victoria, where unemployment rates had fallen to be between 4 and 4½ per cent. The national unemployment rate was expected to edge a little lower to around 4¾ per cent over the following few years. Tightening labour market conditions were expected to put upward pressure on wages, although to date wages growth in Australia and elsewhere had been slower to pick up than in previous expansions.

Turning to the latest data on inflation, members noted that inflation had remained low in the December quarter, with both headline and underlying inflation a little under ½ per cent in the quarter and around 1¾ per cent over the year. Headline inflation had been lower than forecast, largely because fuel prices had been lower than expected in the quarter. Domestic cost pressures had been relatively subdued, partly because wages growth had remained low. More recently, utilities prices had increased only modestly, after substantial increases in previous years, and inflation in the prices of other administered services had declined noticeably as a result of government pricing decisions.

Strong competition in the retail sector had continued to dampen inflation, although deflationary pressures in the retail sector appeared to have eased somewhat in the December quarter. This could have reflected some pass-through of the modest depreciation of the Australian dollar over 2018. The drought had also contributed to higher retail inflation for food, particularly meat.

Inflation in rents had remained subdued and data on newly advertised rents suggested there was little prospect of a pick-up in the near term. Rent inflation had started to trend lower in Sydney, where the rental vacancy rate had risen and was expected to rise further in the near term as more supply becomes available. Rents in Perth had fallen further, although the pace of deflation had eased. Inflation in the cost of new housing construction had trended lower, despite the high level of dwelling investment.

Members noted that the inflation outcome for the December quarter had been fairly close to expectations. However, the forecast pick-up in underlying inflation was now expected to occur a little later than previously expected, mainly as a result of the lower forecast for growth in GDP and downside risks to utilities and administered price inflation in the near term. Underlying inflation was expected to increase to 2 per cent by the end of 2019 (previously by mid 2019) and to reach 2¼ per cent by the end of 2020. Headline inflation was expected to fall to 1¼ per cent in mid 2019 as a result of the fall in fuel prices since the December quarter, on the assumption the lower oil price is sustained.

Members spent some time considering a paper on the implications of recent developments in housing markets for the economic outlook. After rising by almost 50 per cent over the five years to September 2017, national housing prices had fallen by around 8 per cent to be back around mid-2016 levels. Members noted the significantly different developments in housing prices across the country. Housing prices had fallen by 12 per cent in Sydney and by 9 per cent in Melbourne from their peaks in 2017. There had also been significant falls in housing prices in Perth and Darwin over recent years. By contrast, housing prices in Hobart and Canberra had increased over 2018, while housing prices in Adelaide, Brisbane and many regional centres had been flat. Members noted that the cumulative falls in housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne were relatively large by historical standards, and that it was unusual for housing prices to fall significantly in an environment of low mortgage interest rates and a declining unemployment rate.

Members noted that some of the dynamics in housing prices could be explained by the fact that the supply of housing does not respond quickly to changes in demand. In particular, the run-up in housing prices had occurred during a period when housing supply had not picked up sufficiently to match higher demand from more rapid population growth. Over time, higher housing prices had eventually led to a sizeable increase in supply, but this had taken longer than in previous cycles. Another factor weighing on prices was a noticeable decline in demand from foreign buyers in recent years, which had also been apparent in housing markets in some other economies.

Rental vacancy rates are one key indicator of the balance of supply and demand in the housing market. In most states, rental vacancies had been around or somewhat below average at the end of 2018, suggesting supply and demand for housing had been roughly balanced. In Melbourne, despite the fall in prices and large increase in supply, the vacancy rate had declined. By contrast, rental vacancies in Sydney had been increasing and advertised rents had fallen.

Members also noted that housing credit growth had declined further in preceding months and that there had been a notable drop in loan approvals by the major banks. Growth in lending to investors had slowed sharply since mid 2017 to be close to zero, while growth in lending to owner-occupiers had moderated to around 5½ per cent in six-month-ended annualised terms.

The slower growth in lending for housing over the preceding year appeared to reflect weaker demand. Nevertheless, credit conditions for some borrowers had remained tighter than they had been for some time following the strengthening of lending policies and practices over recent years. Liaison with mortgage brokers suggested that the increased public scrutiny associated with the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry may have led some individual loan assessors at banks to apply stricter criteria than specified in official lending requirements. However, banks reported that while loan assessors had been referring more approvals to credit officers, final loan approval rates had remained high. Moreover, lenders had continued to compete for borrowers of high credit quality by offering new loans at lower interest rates than those offered on existing loans.

From a longer-run perspective, members assessed that, following such large increases in housing prices, the effect of the recent price falls on overall economic activity was expected to be relatively small. However, members observed that if prices were to fall much further, consumption could be weaker than forecast, which would result in lower GDP growth, higher unemployment and lower inflation than forecast. From a financial stability perspective, tighter lending standards, an improving labour market and low interest rates were all likely to support households’ capacity to service their debt. Few households were in negative equity positions despite the falls in housing prices, implying that banks’ losses would be limited even if household financial stress were to become more widespread.

Financial Markets

Turning to other financial market developments, members observed that while housing credit growth had declined, business credit growth had strengthened over 2018, with contributions from the foreign banks and the major banks. However, this growth had been driven by increased lending to large businesses.

Members observed that conditions had tightened somewhat in a number of Australian financial markets, in line with global developments. Spreads of bank bond yields to Australian government bonds had widened a little, reflecting a global rise in risk premiums. Nevertheless, yields on bank bonds were little changed around the level of the preceding few years, given the decline in Australian government bond yields. Australian equity prices had declined in the December quarter along with global equity markets, but had recovered in January to be back around their October levels. Members noted that share prices of Australian banks had risen on the morning of the meeting, following the release of the final report of the royal commission and the Government’s response the preceding afternoon.

Money market interest rates had remained higher than a year earlier, contributing to a small increase in banks’ funding costs over the period since then. In response, most lenders had increased their standard variable mortgage interest rates a little since mid 2018. However, the effect of rising standard variable rates had been partly offset by borrowers refinancing at lower rates, given the strong competition for low-risk borrowers. Members noted that, overall, mortgage interest rates remained relatively low.

Turning to global financial markets, members observed that financial conditions had tightened somewhat in recent months in most advanced economies, with increased volatility and a general rise in equity and credit risk premiums. Nevertheless, there had been a partial retracement of the tightening in recent weeks and financial conditions remained accommodative.

At its January meeting, the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had left the federal funds rate unchanged and removed its forward guidance for further interest rate increases. The FOMC had emphasised that it would be patient in making any future adjustments to the federal funds rate, and that future monetary policy decisions would be more closely guided by the incoming data because interest rates were closer to estimates of neutral. The FOMC had also indicated that it would be open to slowing the pace of its planned balance sheet reduction if warranted by economic or market developments. Financial market pricing had shifted to imply that the next move in the federal funds rate was expected to be down, although this was not expected to occur until at least late 2020. Elsewhere, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan were expected to maintain their stimulatory policy settings for an extended period.

Members noted that government bond yields had declined across the major global markets over the preceding two months, reflecting the downward shift in expectations for future policy rates, along with a fall in compensation for future inflation following falls in oil prices. These changes had also reflected increased concerns about downside risks to the outlook for global growth. Australian government bond yields had declined broadly in line with global developments, with long-term government bond yields in Australia remaining around 50 basis points below those in the United States.

There had been a modest depreciation of the US dollar in nominal trade-weighted terms since late 2018, reflecting the more noticeable shift in the outlook for monetary policy in the United States than in other major economies. Members noted that the depreciation had been more pronounced against the Japanese yen, which had appreciated to around its highest level in two years on a trade-weighted basis. The Chinese renminbi had also appreciated modestly over the preceding month, reflecting the depreciation of the US dollar as well as signs of some progress on US–China trade negotiations.

The Australian dollar had depreciated a little further in nominal trade-weighted terms over the preceding two months, largely reflecting the appreciation of the yen and renminbi. However, overall, the Australian dollar had remained within the range observed over the preceding few years. Members observed that there had been two broadly offsetting influences on the Australian dollar exchange rate over the preceding year: the increase in commodity prices and the terms of trade had been supporting the Australian dollar over this period, while the relative decline in Australian government bond yields had been working in the opposite direction.

In global capital markets, corporate bond spreads had risen in recent months and bond issuance had eased, particularly for lower-rated borrowers. There had been some retracement of the increase in corporate borrowing costs in early 2019. Similarly, global equity markets had declined sharply in late 2018, before recovering somewhat since. The widening in credit spreads and decline in equity prices had reflected lower expectations for corporate earnings growth, as well as a rise in the risk premium demanded by investors. However, members observed that overall borrowing costs for corporations had remained low as a result of low government bond yields, and the corrections in these markets had followed an extended period of elevated valuations, particularly in the United States.

In China, the authorities had implemented further targeted measures to support lending to private firms, particularly small-sized enterprises, in the context of slowing economic growth. These firms’ access to finance had been tightened over the course of 2018 as a result of earlier measures by the authorities to reduce risks in the financial system by restricting the availability of ‘shadow finance’. Since the latter part of 2018, the authorities had been encouraging banks to increase their lending to these types of firms, although members noted that larger banks were less accustomed to lending to this sector.

Members noted that conditions in other emerging markets had stabilised in recent months, following a tightening in conditions during 2018. Currencies had appreciated, equity prices had risen, bond spreads had narrowed and capital outflows had moderated across a number of emerging market economies. These developments had reflected policy adjustments in some countries, lower policy rate expectations in the United States and the associated depreciation of the US dollar, and, for oil-importing countries, the decline in oil prices. However, members noted that there remained a risk that financial conditions in emerging markets could tighten further. Concerns about trade tensions and a slowdown in growth, particularly in China, remained particularly important for emerging markets in Asia.

Financial market pricing implied that the Australian cash rate was expected to remain unchanged for a considerable period, with some expectation of a decrease by late 2019.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

In considering the stance of monetary policy, members observed that the global economy had continued to grow at an above-trend pace in 2018, although growth had moderated in some economies in the second half of the year. In particular, growth in China had slowed further and the authorities had continued to ease policy in a targeted way to support growth, while continuing to pay close attention to risks in the financial sector. Labour markets in the advanced economies had continued to tighten and wages growth had picked up. Core inflation had picked up in a number of economies, including the United States. Globally, lower oil prices had led to a decline in headline inflation.

Growth in Australia’s major trading partners was expected to be around trend over the following year or so, but the downside risks had increased. Slowing growth in China and ongoing trade tensions had led to lower growth in global trade. Forecasters had lowered their outlook for global growth and market participants no longer expected a further tightening of monetary policy in the United States. Government bond yields had also declined in most countries, including Australia. More broadly, however, financial conditions had tightened somewhat in most major advanced economies, but remained accommodative. The terms of trade had remained above their trough in early 2016 and the Australian dollar had remained within its narrow range of recent times.

Domestically, growth in output had been weaker than expected in the September quarter. Nevertheless, growth was expected to be a little above trend over the forecast period. The outlook for business investment and spending on public infrastructure was positive. Growth in consumption was expected to be supported by a pick-up in growth in household disposable income, although recent data had prompted a downward revision to the consumption outlook. The outlook for consumption continued to be one of the key uncertainties for the forecasts for the domestic economy, given the environment of declining housing prices, low growth in household income and high debt levels.

Following a significant increase in construction activity and a large run-up in housing prices, housing markets were going through a period of adjustment. Housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne had declined further and the outlook for dwelling investment had been revised lower. In Sydney, rental vacancy rates had been increasing and rent inflation remained low across the country. Credit conditions had tightened for some borrowers and the demand for credit in the housing market, particularly by investors, had slowed noticeably as the dynamics of the housing market had changed. But housing lending rates had remained low and there was strong competition for borrowers of high credit quality.

The labour market had tightened further over 2018 and there had been some pick-up in wages growth. The unemployment rate had declined by ½ percentage point to 5 per cent, its lowest level in over seven years, and employment growth had been above average. The Bank’s forecast was for the unemployment rate to decline a little further over the following few years. The vacancy rate was high and there were reports of skills shortages in some areas. Wages growth was expected to pick up gradually over the following year or so.

Inflation had remained low and stable in both headline and underlying terms over 2018. Underlying inflation was expected to pick up gradually over the forecast period, although headline inflation was expected to decline in the near term because of lower petrol prices.

Members noted that the sustained low level of interest rates over recent years had been supporting economic activity and had allowed for gradual progress to be made in reducing the unemployment rate and returning inflation towards the midpoint of the target. While the labour market had continued to strengthen over the preceding year, less progress had been made on inflation. Taking account of the available information on current economic and financial conditions, as well as the revised forecasts, members assessed that the current stance of monetary policy should continue to allow for further gradual progress on both unemployment and inflation to be made. However, members noted that there were significant uncertainties around the forecasts, with scenarios where an increase in the cash rate would be appropriate at some point and other scenarios where a decrease in the cash rate would be appropriate. Moreover, the probabilities around these scenarios were now more evenly balanced than they had been over the preceding year, when an eventual increase in the cash rate had appeared more likely.

Members would continue to assess the outlook carefully. However, given that further progress in reducing unemployment and lifting inflation was a reasonable expectation, members agreed that there was not a strong case for a near-term adjustment in monetary policy. Rather, they assessed that it would be appropriate to hold the cash rate steady and for the Bank to be a source of stability and confidence while further progress unfolds. Members judged that holding the stance of monetary policy unchanged at this meeting would be consistent with sustainable growth in the economy and achieving the inflation target over time.

The Decision

The Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1.5 per cent.

The Governor In Wonderland

John Adams and I discuss the RBA Governor’s recent speech on “In The Interests Of The People“. This is a brief extract. See the full show by following this link.

RBA “Even Money” On Rate Rise Or Rate Fall

RBA Governor Philip Lowe, addressed the National Press Club today, providing an upbeat assessment of the economy. He was even money on the next rate move, but interestingly he blamed lack of supply of housing not credit supply, or low interest rates for high home prices. He believes wages will rise, eventually. And finally he down rated the international risks, such asset price bubbles, in favour of a arrange of more political risks. Mr optimistic.

And regulators are not be blamed for the poor outcomes from the finance sector, as highlighted by the Royal Commission.

The Aussie slid on the remarks.

Thank you for the opportunity to address the National Press Club. It is an honour to have been invited.

The media and the RBA have a special relationship. Most people in the community hear the RBA’s messages through the media. You report on what we say, you filter it and you critique it. We also help you with your work. The RBA is a reliable source of information and analysis on issues that your audiences care about, including interest rates, housing prices and jobs. This means we have a strong mutual interest in understanding one another. I hope that today will help strengthen that understanding.

This is my first public speech for 2019, so I would like to talk about the year ahead and some of the key issues that the RBA will be focusing on. I will first discuss the global economy and then turn to the Australian economy and particularly the outlook for household spending. I will finish with a few remarks on the outlook for monetary policy.

At the outset, I want to emphasise that we don’t have a crystal ball that allows us to see the future with certainty. I know many of you are looking for definitive answers to questions like, ‘Where will the cash rate be this time next year?’, ‘How much will housing prices fall?’, ‘When will wages growth reach 3 per cent?’. They are all good questions. The reality, though, is that the future is uncertain. None of us can say with certainty what will happen.

What the RBA can do, though, is highlight the issues that are likely to shape the future, explain how we are thinking about those issues, and discuss how they fit into our decision-making framework. That is what I hope to do today.

The Global Economy

I will start with the global economy, because what happens overseas has a major bearing on what happens in Australia. My main point here is that while some of the downside risks have increased, the central scenario for the world economy still looks to be supportive of growth in Australia.

It is worth recalling that 2018 was a good year for the world economy. Growth in the advanced economies was above trend in the first half of the year, unemployment rates reached their lowest levels in many decades, inflation was low and financial systems were stable (Graph 1). These are positive outcomes. We should not lose sight of this.

There was, though, a change in momentum in the global economy late in the year. This change was particularly evident in Europe and it was also evident in China. It has been widely reported in the media, but it is important to keep things in perspective.

Some slowing in global growth was expected, given that labour markets are fairly tight and the policy tightening in the United States was aimed at achieving a more sustainable growth rate. So, I have been a little surprised at some of the reaction to the lowering of forecasts for global growth, which has been quite negative. We need to remember that the IMF’s central forecast is still for the global economy to expand by 3.5 per cent in 2019 and by 3.6 per cent in 2020 (Graph 2). If achieved, these would be reasonable outcomes and not too different from the recent past.

What is of more concern, though, is the accumulation of downside risks. Many of these risks are related to political developments: the trade tensions between the United States and China; the Brexit issue; the rise of populism globally; and the reduced support from the United States for the liberal order that has supported the international system and contributed to a broad-based rise in living standards. One could add to this list the adjustments in China as the authorities rein in shadow financing.

The origins of these diverse issues are complex, but there is a common economic element to some of them: that is, the extended period of little or no growth in real incomes for many people. In a number of countries, growth in real wages has been weak or negative for years. Advances in technology and greater competition as a result of globalisation also mean that many people worry about their own future and that of their children. Politicians, understandably, are responding to these concerns. Time will tell, though, whether the various responses help or not. I suspect that some of them will not.

Over recent months, the accumulation of downside risks has been evident in business and consumer surveys. It was also evident in increased volatility in financial markets around the turn of the year, with declines in equity prices and an increase in credit spreads (Graph 3). Since then, though, markets have been more settled and some of the earlier decline in equity prices has been reversed. This has been partly on the back of a reassessment of the path of monetary policy in the United States, with markets no longer pricing in further increases in US interest rates. There has also been a noticeable fall in long-term government bond yields.

The adjustments in financial markets over our summer sometimes generated reporting that, to me, seemed overly excitable. I lost count of how many times I read the words ‘crash’, ‘plunge’ and ‘dive’. Yet there is a positive side to some of these adjustments, which gets less reported on. The risks associated with stretched valuations in some equity markets have lessened. So, too, have concerns that very low credit spreads could lead to an excessive build-up of risk. And risks in many emerging market economies have also receded, helped by the lower global interest rates and lower oil prices. So it is important to look at the whole picture.

For Australia, what happens in China is especially important. Growth there has slowed. From a medium-term perspective, this has a positive side, as it mainly reflects efforts to rein in risky financial practices and stabilise debt levels. But the slowing is probably faster than the government had hoped for, with the economy feeling the effects of the trade dispute with the United States and the squeezing of finance to the private sector. The authorities have responded by easing policy in some areas, but they are walking a fine line between supporting the economy and addressing the debt problem. There is also the question of how the economy responds to the policy easing.

More broadly, we cannot insulate ourselves completely from the global risks, but keeping our house in order can go a long way to assist. Our floating exchange rate and the flexibility we have on both monetary and fiscal policies provide us with a degree of insulation. So, too, does our flexible labour market. Ensuring that we have predictable and consistent economic policies, credible public institutions and a reform agenda that supports a strong economy can also help in an uncertain world.

The Domestic Outlook

I would now like to turn to the outlook for the Australian economy. Much as is the case globally, the downside risks have increased, although we still expect the Australian economy to grow at a reasonable pace over the next couple of years.

The Australian economy is benefiting from strong growth in infrastructure investment and an upswing in other areas of investment. The labour market is also strong, with many people finding jobs. This year, we will also benefit from a further boost to liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports. The lower exchange rate and a lift in some commodity prices are also assisting. Against this generally positive picture, the major domestic uncertainty is the strength of consumption and the housing market.

We will be releasing a full updated set of forecasts in the Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) on Friday. Close readers of the SMP will notice that we will now be publishing forecasts for a wider set of variables than has previously been the case.[1] We hope that this helps people understand the various forces shaping the economy.

Today, I can give you a summary of the key numbers.

Our central forecast is for the Australian economy to expand by around 3 per cent over 2019 and 2¾ per cent over 2020 (Graph 4). For 2018, the outcome is expected to be a bit below 3 per cent. This type of growth should be sufficient to see further gradual progress in lowering unemployment.

These forecasts are lower than the ones we published three months ago. For 2018, the outcome is affected by the surprisingly soft GDP number in the September quarter and the ABS’s downward revisions to estimates of growth earlier in the year. We are expecting a stronger GDP outcome in the December quarter, with other indicators of economic activity painting a stronger picture than suggested by the September quarter national accounts.

For 2019 and 2020, the forecasts have been revised down by around ¼ percentage point, largely reflecting a modest downgrading of the outlook for household consumption and residential construction. I will talk more about this in a moment.

The outlook for the labour market remains positive. The national unemployment rate currently stands at 5 per cent, the lowest in over seven years (Graph 5). In New South Wales and Victoria, the unemployment rate is around 4¼ per cent. You have to go back to the early 1970s to see sustained lower rates of unemployment in these two states. The forward-looking indicators of the labour market also remain positive. The number of job vacancies is at a record high and firms’ hiring intentions remain strong. Our central scenario is that growth will be sufficient to see a modest further decline in unemployment to around 4¾ per cent over the next couple of years.

The other important element of the labour market is how fast wages are increasing. For some time, we have been expecting wages growth to pick up, but to do so gradually. The latest data are consistent with this, with a turning point now evident in the wage price index (Graph 6). Through our discussions with business we are also hearing more reports of firms finding it difficult to find workers with the necessary skills. In time, this should lead to larger wage rises. This would be a positive development.

Given this outlook, we continue to expect a gradual pick-up in underlying inflation as spare capacity in the economy diminishes (Graph 7). However, the lower forecast for growth means that this pick-up is expected to occur a bit later than we’d previously thought. Underlying inflation is now expected to increase to about 2 per cent later this year and to reach 2¼ per cent by the end of 2020. The latest CPI data were consistent with this outlook. The headline CPI number was, however, a bit lower than we had previously expected, reflecting the decline in petrol prices that started late last year. We expect headline inflation to decline further this year as the full effect of lower petrol prices shows up in the figures.

So that is the summary of the key numbers.

As always, there is a range of uncertainties, many of which will be discussed in the SMP on Friday. Today, though, I would like to focus on the outlook for household spending, which is closely linked to the housing market and the prospects for growth in household income.

Before I do that, I would like to touch on one related uncertainty that we have been paying attention to – that is the supply of credit. This is because a strong economy requires access to finance on reasonable terms. Over recent years there has been a needed tightening of credit standards. But the right balance needs to be struck. As lenders have sought to find that balance, we have had some concerns that the pendulum may have swung too far the other way, especially for small business.

In that context, I welcome the report of the Royal Commission and the Government’s response. The Commission’s recommendations that bear on credit provision are balanced and sensible, and should remove some uncertainty. I also welcome the Commission’s focus on: the importance of service – as opposed to sales – in the financial sector; the necessity of dealing properly with conflict of interest issues; and the importance of accountability when things go wrong. These are all issues I have spoken about on previous occasions. Addressing them is central to rebuilding the all-important trust in our financial system.

Housing Prices and Household Income

But back to household consumption and the housing market.

You might recall that 18 months ago, one of the most talked about issues in the country was the high and rising cost of housing. This was understandable. In some of our cities, purchasing a home had become a very difficult stretch for many people, and this had become a major social issue.

Today, the talk is about prices falling in our two largest cities. We have moved almost seamlessly from worrying that prices were going up, to worrying that they are going down.

There is no single reason for this change, but, rather, it is the result of a number of factors coming together.

One is that housing prices simply increased to the point in Sydney and Melbourne where demand tailed off, as purchasing a home had become very expensive and less attractive as an investment.

A second is that the building boom over recent times significantly increased the supply of dwellings. It took a number of years before the rate of home construction picked up in response to faster population growth, but eventually it did pick up. This explains much of the cycle.

A third factor is that the demand from overseas investors softened, partly in response to the Chinese authorities making it more difficult to move money out of China.

And a fourth factor is that lending standards have been tightened and credit has become more difficult to obtain.

Importantly, unlike most other housing price corrections, this one has not been associated with rising unemployment or higher interest rates. Instead, mainly structural factors – relating to the underlying balance of supply and demand – in our largest cities have been at work.

The question is: what effect will this change have on household spending?

Here, my earlier observation about not having a crystal ball is relevant. At this point, though, what we are seeing looks to be a manageable adjustment in the housing market. It is not expected to derail economic growth. The previous trends in debt and housing prices were becoming unsustainable and some correction was appropriate. We recognise that this correction will have an effect on parts of the economy. But our economy should be able to handle this, and it will put the housing market on a more sustainable footing.

There are a few considerations here.

The first is that the recent housing price declines follow very large increases in prices (Graph 8). Even after the recent declines in Sydney, prices are still 75 per cent higher over the decade. In Melbourne, they are 70 per cent higher. While the price falls are no doubt difficult for some, including people who purchased in the past couple of years, there are many people sitting on very significant capital gains and there are others who now will find it easier to purchase a home. And of course, in a number of cities and much of regional Australia, things have been more stable.

A second consideration is that most households do not change their consumption in response to short-term changes in their wealth. Sensibly, many people tend to take a longer-term perspective. During the recent upswing in housing prices, the strategy of borrowing against the extra equity in your home looked less sensible than it once was, especially as debt levels rose. Some home-owners also see themselves as being part of the ‘bank of mum and dad’. This meant that they refrained from spending the extra equity so that they were able to help their children purchase their own property.

A third and perhaps the most important consideration, is that household income growth is expected to pick up and income growth usually matters more for consumption than changes in wealth.

For some years, growth in nominal aggregate household income has been unusually slow, averaging just 2¾ per cent since 2016 (Graph 9). For some home-owners, rising housing prices have provided an offset to this, even though the effect may have been smaller than in the past. As a result, aggregate consumption has grown faster than income for the past few years. But a shift is now taking place. Over the next year, we are expecting a pick-up in household disposable income to provide a counterweight to the wealth effects of lower housing prices.

Labour market outcomes are key to this assessment. Continued employment growth and higher wages growth should boost disposable incomes. The announced tax cuts should also help here. In our central scenario, consumption is expected to grow at around 2¾ per cent over the next couple of years, broadly in line with expected growth in disposable income. This is a bit lower than our earlier forecast for consumption.

There are, of course, other possible outcomes. Continued low income growth, together with falling housing prices, would be an unwelcome combination and would make for a softer outlook for the economy. Some Australian households have high levels of debt, so there is a degree of uncertainty about how they would respond to this combination. So we are monitoring things closely.

The adjustment in the housing market is also affecting the economy through residential construction activity and the spending that occurs when people move homes. Residential construction activity is currently around its peak level and the large pipeline of approved projects is expected to support activity for a while. Developers, though, are finding it more difficult to sell apartments off the plan, and lenders are less willing to provide finance. Sales of new detached dwellings have also slowed. The central forecast is for dwelling investment to decline by about 10 per cent over the next two and a half years.

Putting all this together, our economy is going through an adjustment following the turn in the housing markets in our largest cities. It is important that we keep this in perspective though.

The correction in the housing market follows an extended period of strength. It is largely due to structural supply and demand factors, and is occurring against the backdrop of a robust economy and an expected pick-up in income growth. Our financial institutions are also in a strong position to deal with the adjustment. Indeed, lending standards were strengthened as the upswing went on. From this perspective, the adjustment in the housing market is manageable for the financial system and the economy. This adjustment will also help increase the affordability of housing for many people. Even so, given the uncertainties, we are paying very close attention to how things evolve.

Monetary Policy

This brings me to monetary policy.

The cash rate has been held steady at 1½ per cent since August 2016. This setting has helped support the economy. The Reserve Bank Board has sought to be a source of stability and confidence while our economy adjusted to the end of the mining investment boom and responded to the shifting sands of the global economy.

Over the past couple of years, economic conditions have been moving in the right direction. The labour market has strengthened, and the unemployment rate has fallen and a further decline is expected. Inflation is also above its earlier trough, although it has not changed much over the past year. Our expectation has been – and continues to be – that the tighter labour market and reduced spare capacity will see underlying inflation rise further towards the midpoint of the target range. Given this, we have maintained a steady setting of monetary policy while the labour market strengthens and inflation increases.

Looking forward, there are scenarios where the next move in the cash rate is up and other scenarios where it is down. Over the past year, the next-move-is-up scenarios were more likely than the next-move-is-down scenarios. Today, the probabilities appear to be more evenly balanced.

We will be monitoring developments in the labour market closely. If Australians are finding jobs and their wages are rising more quickly, it is reasonable to expect that inflation will rise and that it will be appropriate to lift the cash rate at some point. On the other hand, given the uncertainties, it is possible that the economy is softer than we expect, and that income and consumption growth disappoint. In the event of a sustained increased in the unemployment rate and a lack of further progress towards the inflation objective, lower interest rates might be appropriate at some point. We have the flexibility to do this if needed.

The Board will continue to assess the outlook carefully. It does not see a strong case for a near-term change in the cash rate. We are in the position of being able to maintain the current policy setting while we assess the shifts in the global economy and the strength of household spending.

It has long been the Board’s approach to avoid reacting to the high-frequency ebb and flow of news. Instead, we have sought to keep our eye on the medium term and put in place a setting of monetary policy that helps deliver on our objectives of full employment, an inflation rate that averages between 2 and 3 per cent, and financial stability.

Thank you for listening. I look forward to answering your questions.

RBA Holds, Of Course

At its meeting today, the Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1.50 per cent.

I think they are living in a parallel universe!

The global economy grew above trend in 2018, although it slowed in the second half of the year. Unemployment rates in most advanced economies are low. The outlook for global growth remains reasonable, although downside risks have increased. The trade tensions are affecting global trade and some investment decisions. Growth in the Chinese economy has continued to slow, with the authorities easing policy while continuing to pay close attention to the risks in the financial sector. Globally, headline inflation rates have moved lower due to the decline in oil prices, although core inflation has picked up in a number of economies.

Financial conditions in the advanced economies tightened in late 2018, but remain accommodative. Equity prices declined and credit spreads increased, but these moves have since been partly reversed. Market participants no longer expect a further tightening of monetary policy in the United States. Government bond yields have declined in most countries, including Australia. The Australian dollar has remained within the narrow range of recent times. The terms of trade have increased over the past couple of years, but are expected to decline over time.

The central scenario is for the Australian economy to grow by around 3 per cent this year and by a little less in 2020 due to slower growth in exports of resources. The growth outlook is being supported by rising business investment and higher levels of spending on public infrastructure. As is the case globally, some downside risks have increased. GDP growth in the September quarter was weaker than expected. This was largely due to slow growth in household consumption and income, although the consumption data have been volatile and subject to revision over recent quarters. Growth in household income has been low over recent years, but is expected to pick up and support household spending. The main domestic uncertainty remains around the outlook for household spending and the effect of falling housing prices in some cities.

The housing markets in Sydney and Melbourne are going through a period of adjustment, after an earlier large run-up in prices. Conditions have weakened further in both markets and rent inflation remains low. Credit conditions for some borrowers are tighter than they have been. At the same time, the demand for credit by investors in the housing market has slowed noticeably as the dynamics of the housing market have changed. Growth in credit extended to owner-occupiers has eased to an annualised pace of 5½ per cent. Mortgage rates remain low and there is strong competition for borrowers of high credit quality.

The labour market remains strong, with the unemployment rate at 5 per cent. A further decline in the unemployment rate to 4¾ per cent is expected over the next couple of years. The vacancy rate is high and there are reports of skills shortages in some areas. The stronger labour market has led to some pick-up in wages growth, which is a welcome development. The improvement in the labour market should see some further lift in wages growth over time, although this is still expected to be a gradual process.

Inflation remains low and stable. Over 2018, CPI inflation was 1.8 per cent and in underlying terms inflation was 1¾ per cent. Underlying inflation is expected to pick up over the next couple of years, with the pick-up likely to be gradual and to take a little longer than earlier expected. The central scenario is for underlying inflation to be 2 per cent this year and 2¼ per cent in 2020. Headline inflation is expected to decline in the near term because of lower petrol prices.

The low level of interest rates is continuing to support the Australian economy. Further progress in reducing unemployment and having inflation return to target is expected, although this progress is likely to be gradual. Taking account of the available information, the Board judged that holding the stance of monetary policy unchanged at this meeting would be consistent with sustainable growth in the economy and achieving the inflation target over time.

RBA Says Credit Hits New High, But Growth Is Lower Again

The December 2018 data from the RBA has been released today, and credit growth continues to slow, led down by both housing and business finance. That said total credit is still expanding, and housing credit reached a new record, $1.8 trillion dollars. Within that Owner occupied loans were reported at $ 1.21 trillion dollars and Investment loans $0.59 trillion, accounting for 32.9% of all housing lending. Credit to business was up a little to 32.8% of all lending stock. Personal credit shrank again.

The share of lending for housing investment fell again, while the business mix was up just a little.

Total credit for housing was an annualised 4.7% compared with 6.3% a year ago. Personal credit was down again, to -2.0% over the past year, compared with -1.1% a year before, and business credit was at 4.8% compared with 3.1% a year back.

Within the housing sector, home lending for investment purposes was at 1.1% and for owner occupation a (still massive) 6.5%. Still way higher than inflation and wages, so household debt ratios will continue to deteriorate.

The monthly movements show a fall in business lending momentum and owner occupied lending, though a small uptick in investor loans, if from a low base.

The APRA data is also out today, so we will look at this later… But we can conclude the overall growth in housing lending is still building more risks in the market, despite all the hype. Credit loosening should be resisted.

Pressure mounts on RBA to cut rates

Another blowout in bank funding costs is adding to the pressure for an RBA rate cut, according to a leading forecaster, via InvestorDaily.

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver is confident that the Reserve Bank will be forced to cut the cash rate by 50 basis points to 1 per cent this year.

He explained that Australian economic data has been soft in recent weeks with weak housing credit, sharp falls in home prices in December, another plunge in residential building approvals pointing to falling dwelling investment, continuing weakness in car sales, a loss of momentum in job ads and vacancies and falls in business conditions for December.

“Retail sales growth was good in November but is likely to slow as home prices continue to fall,” Mr Oliver said.

“Income tax cuts will help support consumer spending, but won’t be enough so we remain of the view that the RBA will cut the cash rate to 1 per cent this year.”

Meanwhile, another spike in funding costs has seen a number of lenders hike their mortgage rates in the first few weeks of 2019.

Bank of Queensland lifted rates by 18 basis points, while home loan providers Virgin Money and HomesStart Finance have also announced interest rate rises.

“The gap between the 3-month bank bill rate and the expected RBA cash rate has blown out again to around 0.57 per cent compared to a norm of around 0.23 per cent,” Mr Oliver said.

“As a result, some banks have started raising their variable mortgage rates again. This is bad news for households seeing falling house prices. The best way to offset this is for the RBA to cut the cash rate as it drives around 65 per cent of bank funding.”

Digital Finance Analytics principal Martin North believes even small rate rises could see more households pushed into mortgage stress and increase the risk of default among those already under pressure to meet their monthly repayments.

“The other point is that it will actually tip more borrowers into severe stress, that’s when you’ve got a serious monthly deficit. That’s the leading indicator for default 18 months down the track,” he said.

Decoding The Australian Economy

We review the RBA’s latest chart pack and discuss the key themes in the economy, including household debt, home prices, credit growth and international debt exposure.

The Debt Machine Is Alive And Well

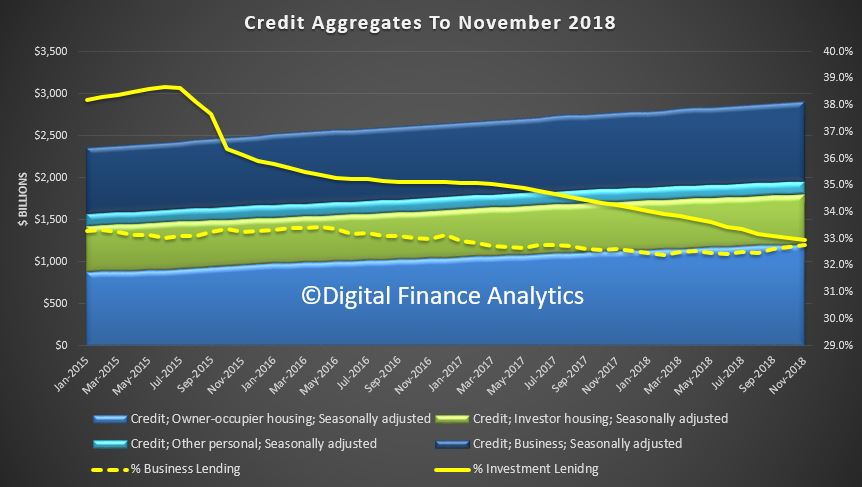

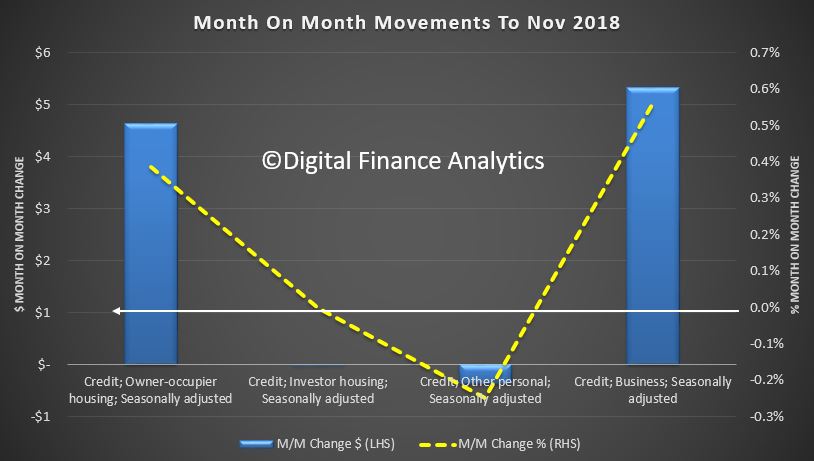

As we approach the end of the year, we got some stats from the RBA on credit to the end of November. Whilst the debt is growing the value of the housing assets are falling, this is a nasty pincer movement!

Their credit aggregates reveals that in seasonally adjusted terms total credit rose by 0.34% or $9.9 billion dollars, to a new record of $2.9 trillion dollars.

Within that credit for owner occupied housing rose 0.38%, or $4.63 billion to a new record $1.21 trillion dollars, lending for property investment was flat, standing at $0.59 trillion dollars and lending for business rose 0.56%, or $5.32 billion to $0.95 trillion dollars, another record. The proportion of business lending to all lending rose to 32.8%, while the share of residential property lending for investment property fell to 32.9%, the lowest in years (but still too high in my book!). Credit growth is too fast.

The trend charts show that on a 12 month basis, investment lending has now only growth 1.1%, while owner occupied lending is still running at 6.8%, still faster than business lending. Personal credit continues to fall.

This indicates that despite all the hype about tight lending, loans are still being written, at a growth rate which is well above inflation and income. As a result the total debt burden is still rising. RBA please note.

We can see the consequences working out by looking at the latest Household Finance Ratios from the RBA, using ABS data

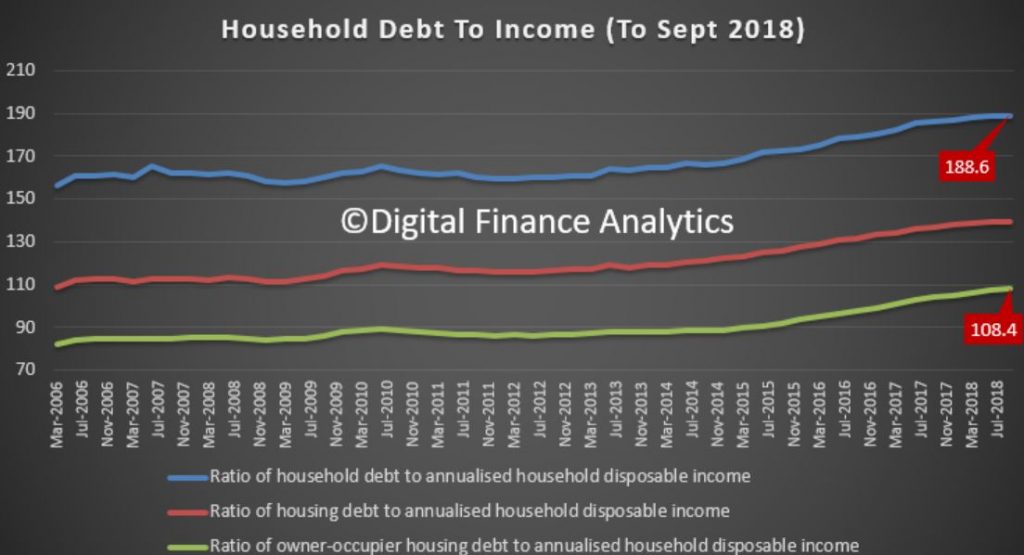

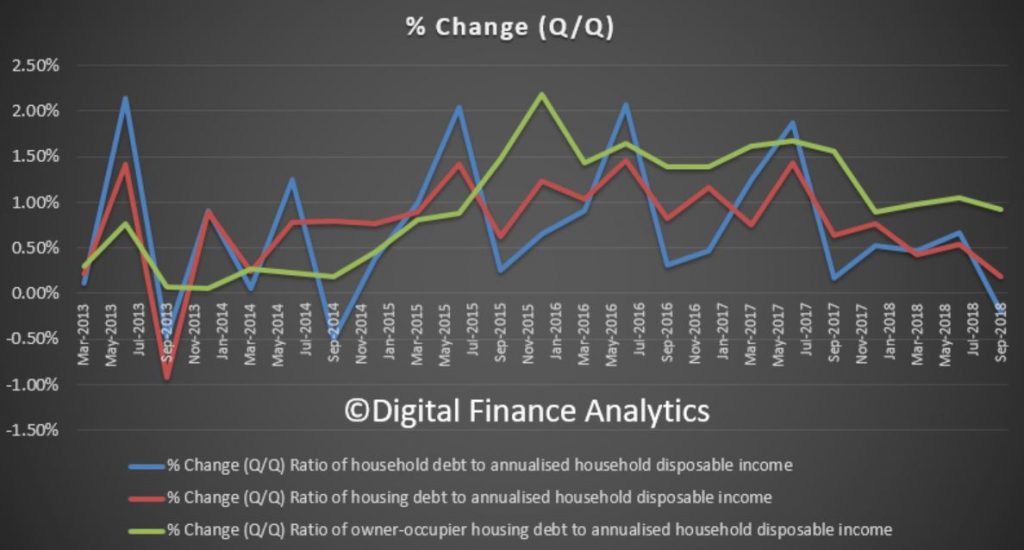

This shows that total household debt to income to September 2018 fell from 189 to 188.6, whilst the housing debt to income rose from 139.4 to 139.6 and the owner occupied ratio rose from 107.4 to 108.4. Now this ratio includes households and unincorporated businesses – small businesses essentially. So we see the continued consolidation of debt around housing, while other forms of debt, such as credit cards, diminished. In fact, the change quarter on quarter for owner occupied housing debt is close to 1%, so have no doubt, debt relative to income for housing is still rising.

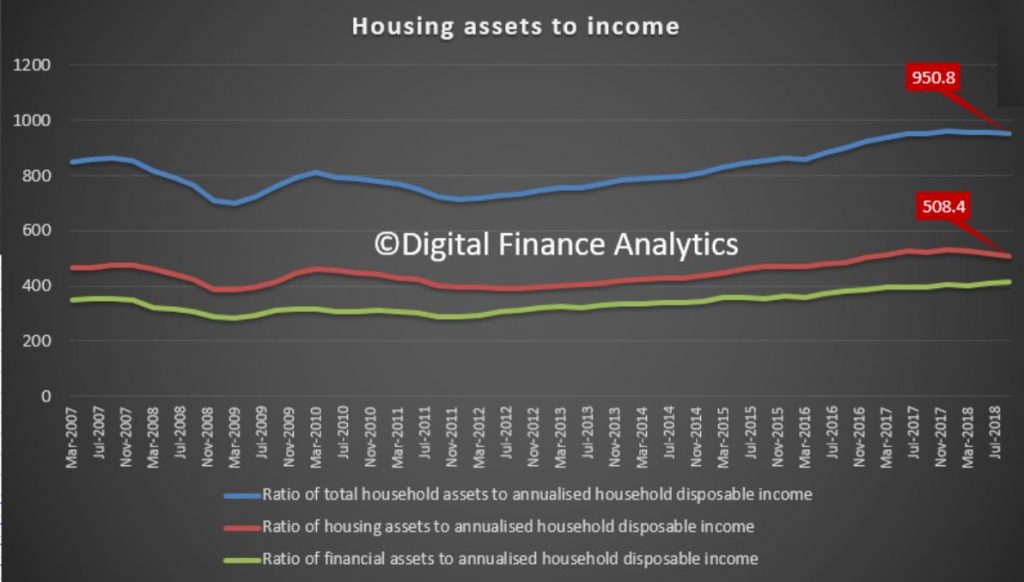

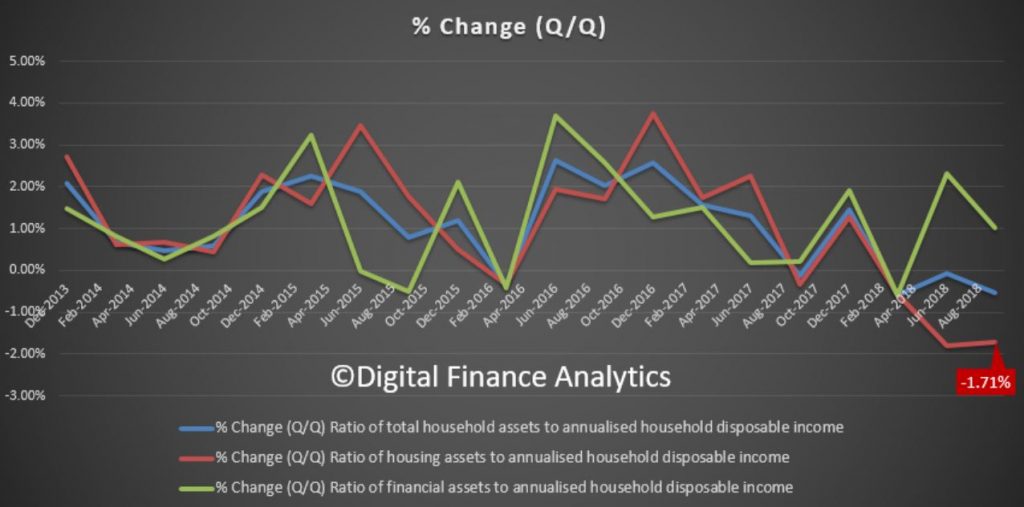

The assets to income data in the same series fell, thanks to the fall in value of housing.

The ratio of household assets to income fell from 956.0 to 950.8, the ratio of housing assets to income fell from 517.3 to 508.4, down 1.7% in the quarter and 2.7% for the year to date, while the ratio of financial assets (stocks etc.) lifted from 410.3 to 414.5 (though will be lower now thanks to the recent market falls). In other words, whilst the debt is growing the value of the housing assets are falling – a double whammy.

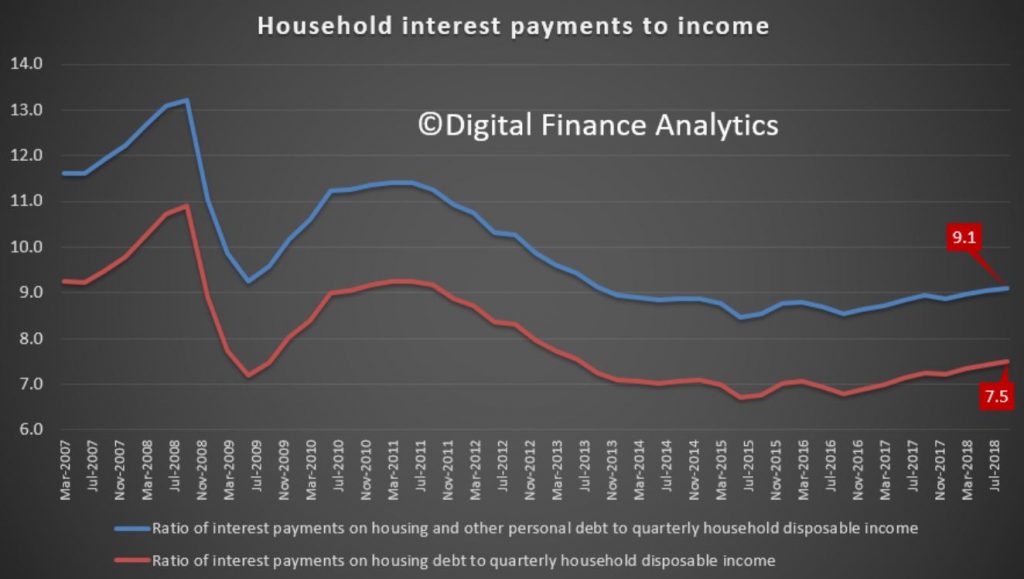

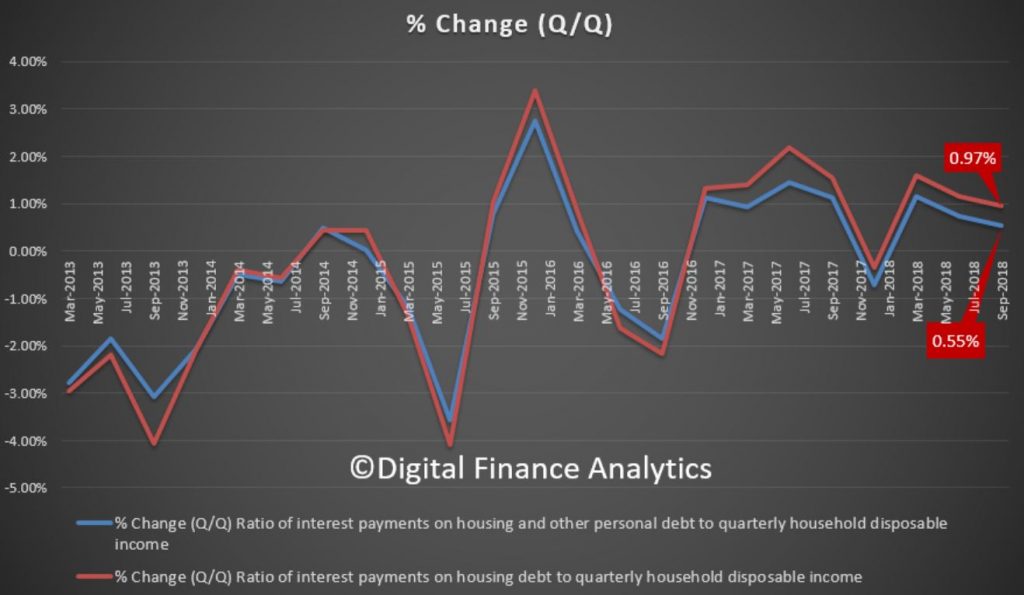

The final dimension is interest payments to debt, both of which are higher (thanks to bigger loans and only small changes in mortgage rates).

The ratio of housing debt interest repayments to income rose from 7.4 to 7.5 per cent and interest payments on all debt rose from 9.0 to 9.1 percent. This is confirming the growth trend since 2016, where the out of cycle interest repayments hit.

The point to note here is that the one third of households with mortgage debt are seeing a rise in the share of income going to support the interest repayments – at these extremely low, emergency interest rates. And that is the point, the averages mask the marginal borrower who remains under extreme pressure, which is why mortgage stress continues to rise. We will report on the December data in a week or so.

So the key take away as we move into 2019 is the debt machine is still working, more households are being encouraged to get deeper into debt, despite the clear evidence of massive over borrowing. A strategy applauded by the RBA, the Treasury and the Banks!

We really need a change in strategy because debt fueled household consumption and property speculation will be one of the nails in the economies coffin down the track. Interest rates will rise. The other is sporty corporate borrowing, but that is a story for another day!

Finally, seasons greetings to all our followers, and our best wishes for (a debt free) 2019!