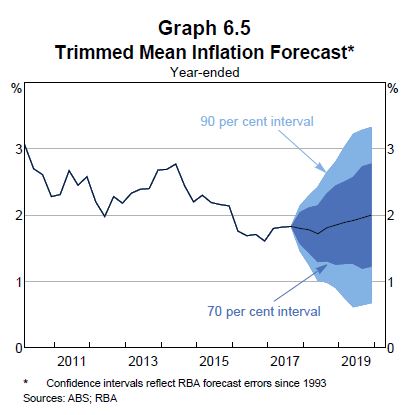

The RBA’s latest Statement on Monetary Policy, released today, highlights the tension between stronger global growth, reflected in expected rising interest rate benchmarks in several countries, including the USA; and weaker inflation and growth in Australia. As a result, pressure to lift the cash rate here appears lower than before. Underlying inflation is expected to remain steady at around 1¾ per cent until early 2019, before increasing to 2 per cent.

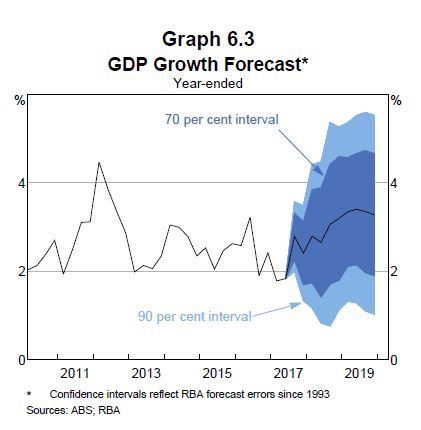

GDP growth should strengthen over the rest of the forecast period as the drag from mining investment comes to an end and public demand and non-mining business investment continue to support growth.

GDP growth should strengthen over the rest of the forecast period as the drag from mining investment comes to an end and public demand and non-mining business investment continue to support growth.

So, they are holding to the above 2% inflation rate, and 3% growth rate over their forecast period.

So, they are holding to the above 2% inflation rate, and 3% growth rate over their forecast period.

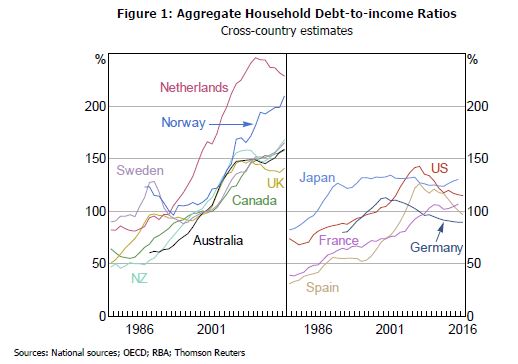

However, if rates do stay lower for longer here, it may benefit households already suffering under mountains of mainly housing related debt, but put pressure on the dollar and terms of trade, as rates overseas climb sucking investment dollars away from Australia and lifting funding costs.

Here is their summary:

The Australian economy is expected to expand at a solid pace over the next couple of years, and labour market developments have been quite positive of late. The drag on growth from the end of the mining investment boom has eased and is likely to end sometime in the next year or so. Investment in the non-mining sector has been increasing but growth in consumption has been below average. Inflation and wage growth remain low. Both are expected to increase only gradually over time.

A number of factors are serving to hold inflation down. Wage growth has remained low and strong competition in the retail sector is dampening retail inflation across a broad range of goods. Although the unemployment rate has declined and is expected to fall further, some spare capacity is likely to remain in the labour market in the period ahead. It is also likely that structural factors and the adjustment following the terms of trade boom have been working to contain wage growth. Stronger labour market conditions are nonetheless expected to lead to a pick-up in wage growth over time. Important uncertainties influencing the outlook for inflation include the questions of how much wage growth might pick up as the labour market tightens, and how quickly the resulting increase in labour costs might feed into inflation.

Both headline and trimmed mean inflation were a little below 2 per cent over the year. Short-run fluctuations in the prices of volatile items such as fruit and vegetables added to the ongoing dampening effects of strong retail competition on the prices of tradeable goods and services.

Slow growth in labour costs and rents also contributed to inflation remaining low. Working in the opposite direction, cost pressures are feeding through into the prices of newly built homes. Tobacco and electricity prices have also boosted headline inflation and are expected to continue to do so. Headline inflation could also be a bit higher in the December quarter because petrol prices have risen noticeably in recent weeks.

Further out, the various measures of inflation are expected to reach 2–2¼ per cent by the end of the forecast period. The forecasts reflect an expectation that wage growth will gradually pick up. They also incorporate the effect of the slight appreciation of the Australian dollar since midyear. If the exchange rate were to appreciate further, economic activity and inflation would be likely to pick up more slowly than currently forecast. The Bank’s assessment of how inflationary pressures are likely to evolve is not affected by the forthcoming update to the weights used to calculate the consumer price index, although the forecasts have been lowered a little to account for this methodological change.

The outlook for the Australian economy is little changed from three months ago. Quarterly GDP growth is expected to have eased slightly in the September quarter. Beyond that, growth is forecast to average about 3 per cent over the next couple of years. Growth in resource exports will more than offset the diminishing drag from lower mining investment. The mining sector is therefore likely to contribute to economic growth over the forecast period, as will other categories of exports. Chinese demand for resources for steel production has supported bulk commodity prices. However, the terms of trade are generally expected to fall over the forecast period, reaching a level somewhat above the trough recorded in early 2016, because Chinese steel demand is expected to be lower, while global supply of iron ore will have increased further.

The outlook for business investment looks to be more positive than it has for some time. Reported business conditions are at a high level and, following recent data revisions, non‑mining business investment now appears to be increasing by more than previously thought. Forward-looking indicators, especially those for non-residential building, are consistent with this continuing. A considerable amount of public infrastructure work is planned or underway, particularly in the south-eastern states. This is contributing to activity of the private-sector firms undertaking this work on behalf of the public sector, as well as encouraging some of those firms to invest more themselves.

Growth in household consumption looks to have slowed in the September quarter given recent weakness in retail spending. Consumption growth is expected to pick up gradually, but slow growth in incomes and high levels of debt are constraining factors. The slow growth in household income has been driven primarily by unusually soft outcomes for average earnings of

employees as measured in the national accounts, which has more than offset the effects of strong employment growth. Wage growth has been slow, averaging an annual rate of around 2 per cent in recent quarters, but average earnings growth has been slower still. Shifts in the composition of employment within industries to lower-paid work might partly explain this, along with the usual volatility in this measure of average earnings.Labour market conditions have strengthened considerably in recent months. Growth in employment has continued to outpace that of the working-age population. Employment has increased in all states and has been concentrated in full-time jobs. Forward-looking indicators of labour demand suggest that above-average employment growth will continue in coming quarters. Labour supply has also expanded in all states, driven by increasing participation of women and older workers retiring later than in the past. Measures of unemployment and underutilisation have declined.

Dwelling investment looks to have peaked earlier than previously expected, and the pipeline of projects to be completed is now being worked down in some states. Dwelling investment is nonetheless expected to remain at a high level over the next couple of years, but not to contribute to overall economic growth. This implies that housing supply will continue to expand at an above-average rate, which would tend to weigh on housing prices and rents in some markets.

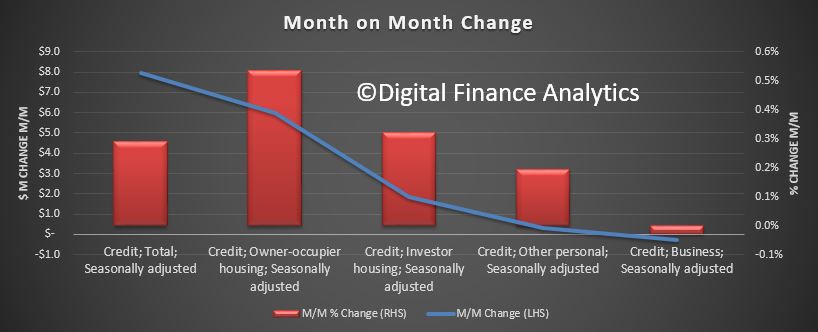

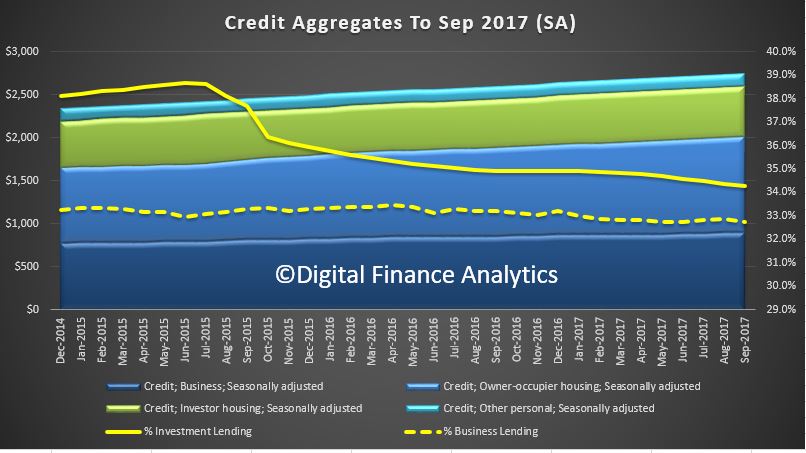

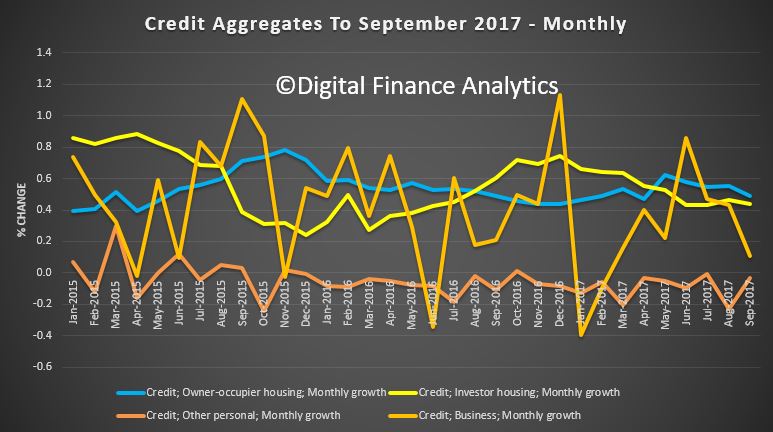

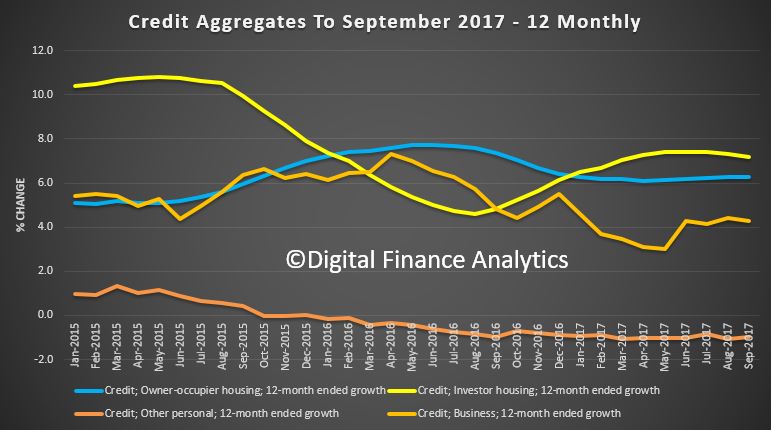

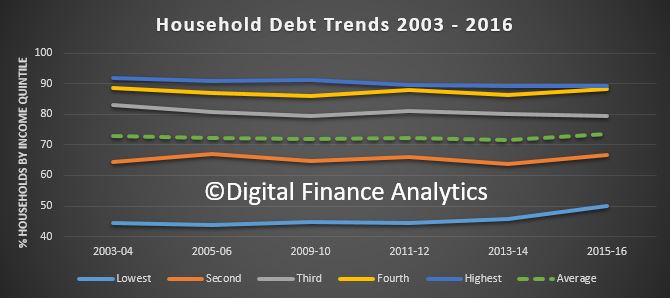

Housing credit growth has eased a little, and the profile of new lending has shifted away from interest-only and other riskier types of lending. This suggests that recent prudential measures are helping to address risks in household balance sheets. Household debt remains high, however, and continues to increase faster than household income. Conditions in the established housing market have eased noticeably in Sydney, but have remained relatively strong in Melbourne. Housing prices are little changed recently in Brisbane and Perth. Growth in rents is below average in most cities, while in Perth rents continue to fall and vacancy rates are rising.

The global economy has strengthened further over the course of 2017. GDP growth was stronger than expected in the September quarter in most major economies for which data are available, and this strength appears to have been maintained. Conditions in manufacturing sectors are particularly buoyant, supported by the ongoing expansion in global trade, which is particularly benefiting economies in east Asia.

Growth in China continues to be stronger than earlier expected. Growth in infrastructure and construction activity remains robust and upstream price pressures have emerged. Announcements during the recent Party Congress pointed to the authorities’ continued resolve to tackle financial sector risks and the high level of debt. Also consistent with the authorities’ stated policy priorities, cuts to steel production have been mandated to improve environmental outcomes. This might reduce Chinese demand for iron ore and coking coal, at least temporarily. Iron ore prices have fallen in recent months partly in anticipation of this. More broadly, growth in China is expected to slow a little in coming years, because the working-age population is declining and the authorities seem less likely to use policy stimulus to maintain growth around current rates.

Conditions in the major advanced economies continue to improve. Labour markets have tightened further and unemployment rates have reached low levels in the United States, Japan, Germany and some smaller euro area member countries. Ongoing policy stimulus, a recovery in investment and the recent tendency for labour supply to increase all suggest that this above trend growth could persist for a while yet. Wage growth has so far picked up only a little in these economies, however, and inflation generally remains low. The experience of economies with tighter labour markets than Australia’s shows how long it can take for pricing pressures to emerge in an environment of strong local and global competition.

Central banks in a few countries have begun to raise policy rates and the US Federal Reserve is reducing the size of its balance sheet. Financial market pricing suggests that market participants expect policy accommodation globally to be withdrawn only gradually. Consequently, financial conditions continue to be very accommodative. Risk and term premiums have narrowed to low levels, as have spreads on corporate bonds. This has encouraged a rise in corporate bond issuance. Equity prices have risen in most markets. Financial market volatility remains low.

The stimulatory setting of monetary policy in Australia has supported the economy and helped generate a decline in unemployment. Over the period ahead, further progress on reducing spare capacity in the economy is expected, which in turn would support the forecast gradual increase in inflation. Accordingly, at its recent meetings the Reserve Bank Board has judged that holding the cash rate at its current level of 1.5 per cent would be consistent with sustainable growth in the economy and achieving the medium-term inflation target.