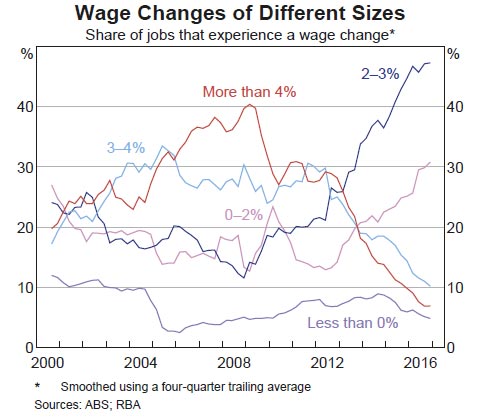

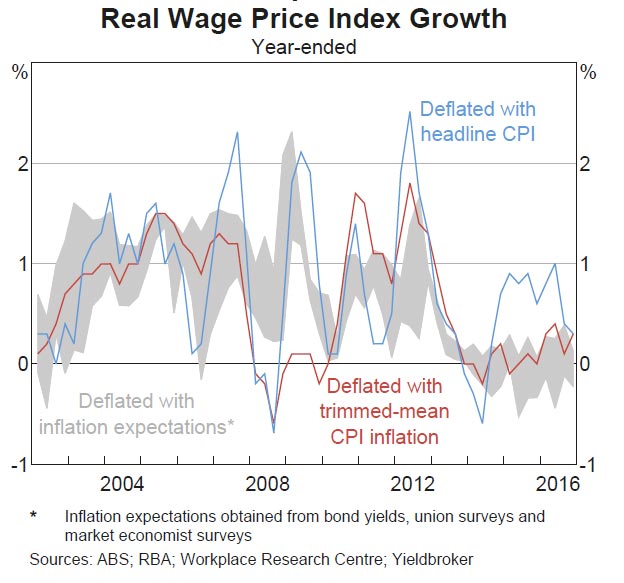

The latest edition of the RBA Bulletin included a section of wage growth and this chart. Inflation adjusted wage growth is close to zero. Not good for households with large mortgages. Interestingly they did not separate public and private sector growth, out data suggests public sector employees are doing better than those in the private sector!

The RBA says the job-level micro WPI data provides further insights into the slowing of wage growth in Australia over recent years. Following the

The RBA says the job-level micro WPI data provides further insights into the slowing of wage growth in Australia over recent years. Following the

decline in the terms of trade, there has been a reduction in the average size of wage increases.

This has been particularly pronounced in mining and mining-related wage industries. The increasing share of wage outcomes around 2–3 per cent also provides further support for the hypothesis that inflation outcomes and inflation expectations influence wage-setting.

The Bank’s expectation is that wage growth will gradually pick up over the next few years, as the adjustment following the end of the mining boom runs its course. The extent of the recovery will, in large part, depend on how wage growth will respond to improving labour market conditions, including the level of underutilisation.

They observe that wage growth across all pay-setting methods has declined. Wage growth in industries that have a higher prevalence of individual agreements has declined most significantly over recent years,

following strong growth in the previous few years. This may reflect the fact these industries have been influenced by the large terms of trade

movements, but may also indicate that wages set by individual contract can respond most quickly to changes in economic conditions.

Wage growth in industries with a higher share of enterprise bargaining agreements have the lowest wage volatility, as the typical length of an

agreement is around two and a half years. While changes in wage growth and labour market outcomes by pay-setting may reflect differences in wage flexibility or bargaining power, these can be difficult to distinguish from a wide range of other determinants of wages, including variation

in industry performance, the balance of demand and supply for different skills, and productivity.

The share of wage rises between 2–3 per cent has increased to now account for almost half of all wage changes. This may indicate some degree of anchoring to CPI outcomes and/or the Bank’s inflation target. Decisions by the Fair Work Commission, which sets awards and minimum wage outcomes, are heavily influenced by the CPI. A little over 20 per cent of employees have their pay determined directly by awards, and it is estimated pay outcomes for a further 10–15 per cent of employees

(covered by either enterprise agreements or individual contracts) are indirectly influenced by awards.