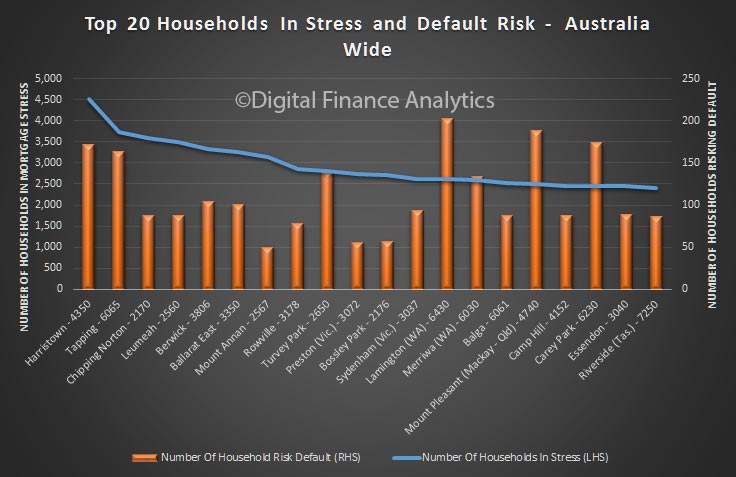

The pain is more severe in Harristown in Queensland, about 130km west of Brisbane, where more than 4500 households are in difficulty.

For the banks, more than 370 in these areas alone are likely to default, or fall more than 30 days behind on repayments, according to data from Digital Finance Analytics.

Research covering the top 20 postcodes with the greatest mortgage stress features many country areas but Melbourne’s Essendon and Preston each have around 2500 households in difficulty, as does western Sydney’s Bossley Park.

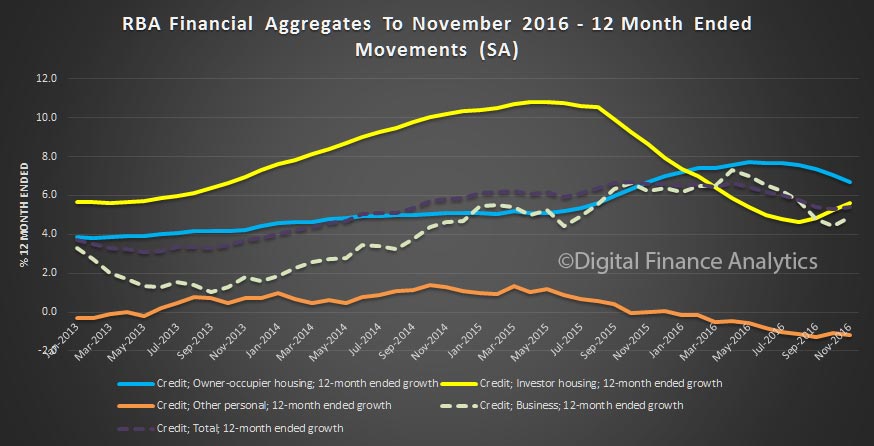

Despite record low interest rates and unemployment below 6 per cent, Standard & Poor’s yesterday said arrears ticked higher in October and the proportion of “non-conforming” borrowers behind on payments was near record levels.

DFA’s data, based on a rolling survey of 2000 households a month, suggests the trend will worsen. It also suggests first time home buyers who received help from the “bank of mum and dad” were more likely to default.

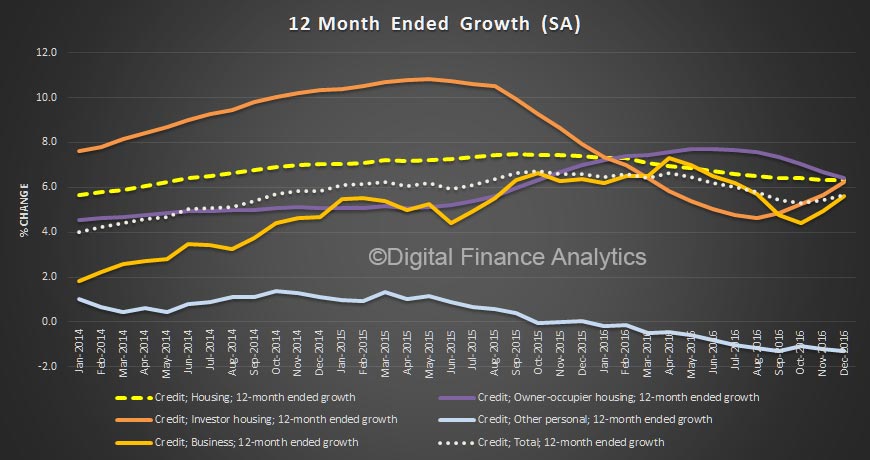

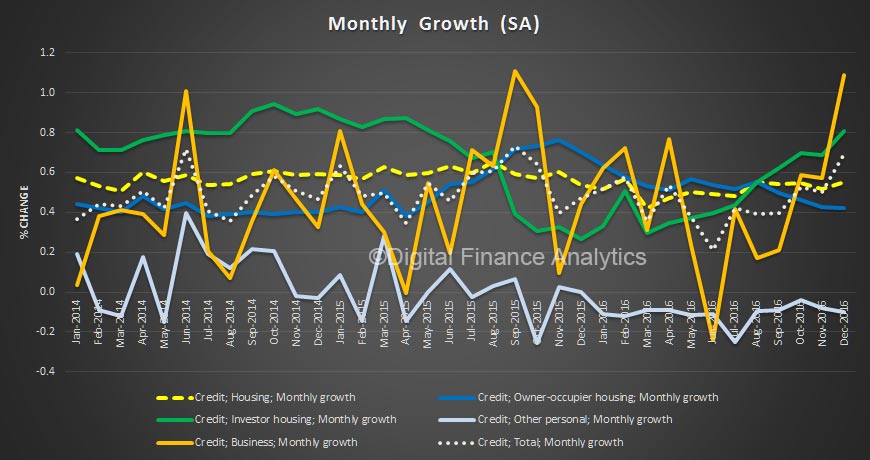

“The issue will be what happens to interest rates. If interest rates don’t go up, then some of this won’t flow through, but I think all the expectations are that interest rates will rise,” said DFA analyst Martin North, who is factoring in a 50 basis point increase in rates next year.

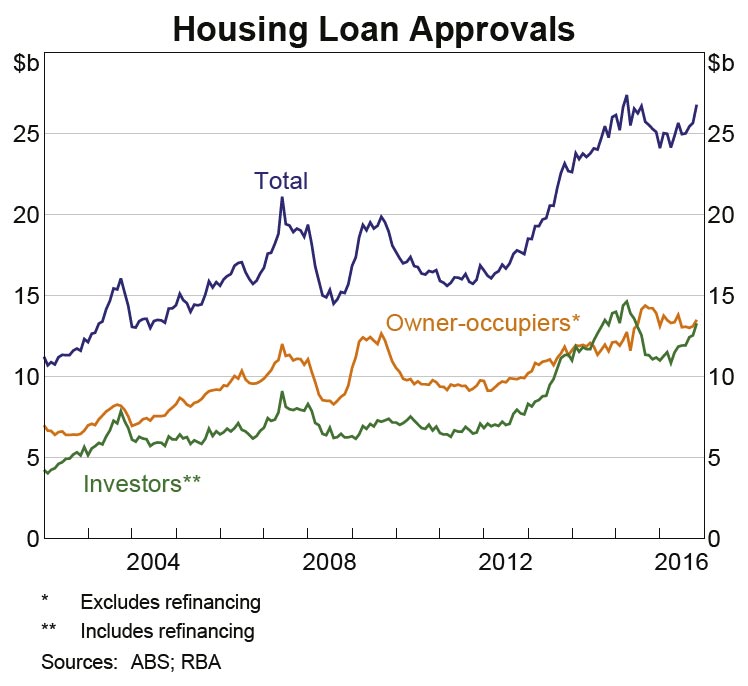

Banks in recent weeks have hiked mortgage rates for many customers out of sync with any RBA changes, which analysts said could put customers under greater pressure amid meagre income growth.

Mr North said: “My own models predict a higher rate of loss than they (banks) are currently predicting themselves.”

The RBA yesterday signalled borrowers were unlikely to win any imminent reprieve on their debt repayments early next year.

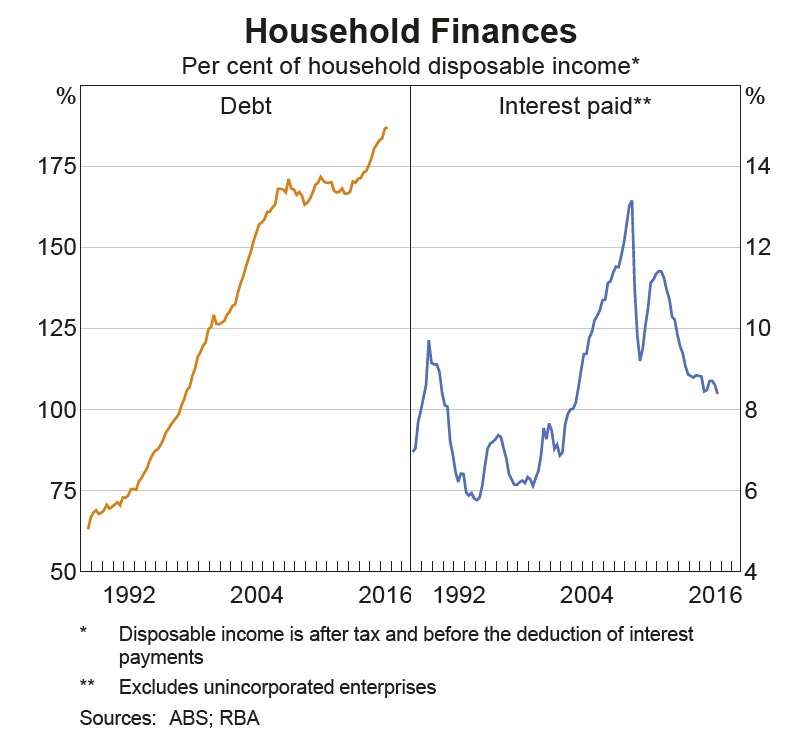

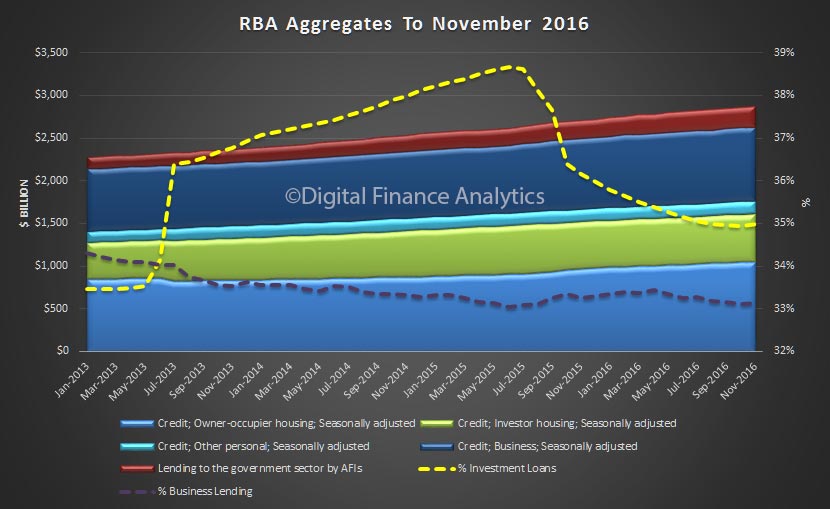

After cutting rates since late 2011, the RBA’s minutes of its monthly board meeting revealed greater concern about the “balance” between low rates supporting economic growth and the “potential risks to household balance sheets”.

“Members recognised that this balance would need to be kept under review,” the RBA said.

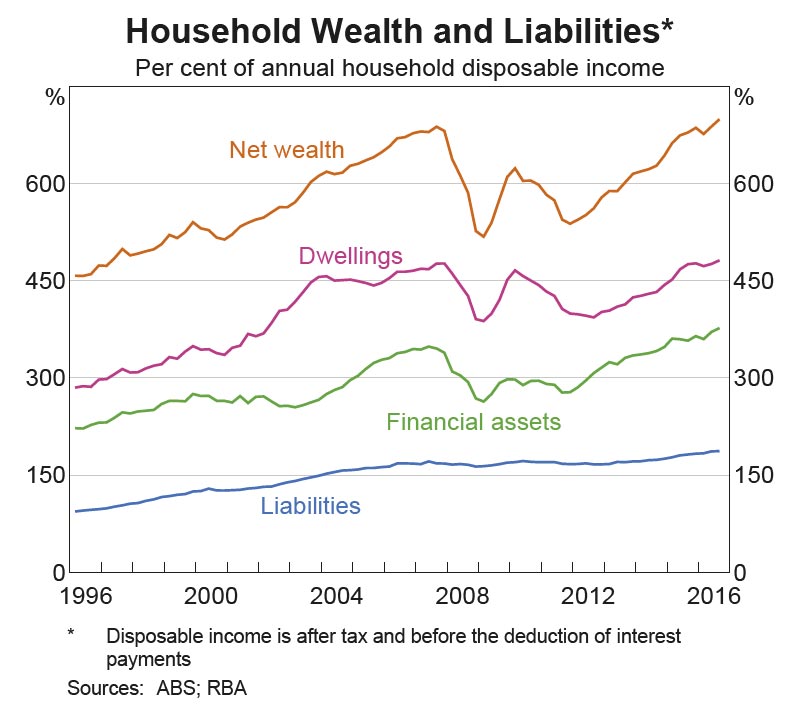

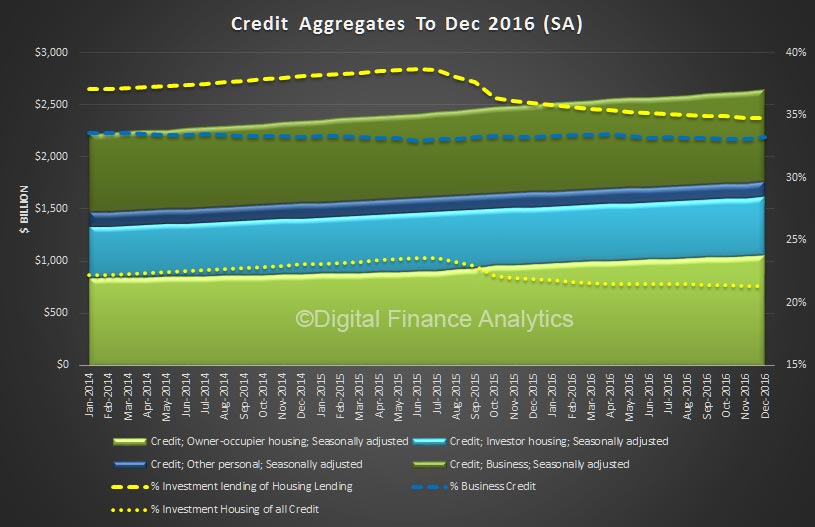

Westpac chief economist Bill Evans said the RBA was concerned the benefits to spending from lower rates were not compensating for the instability in asset markets, heightened by record high household debt.

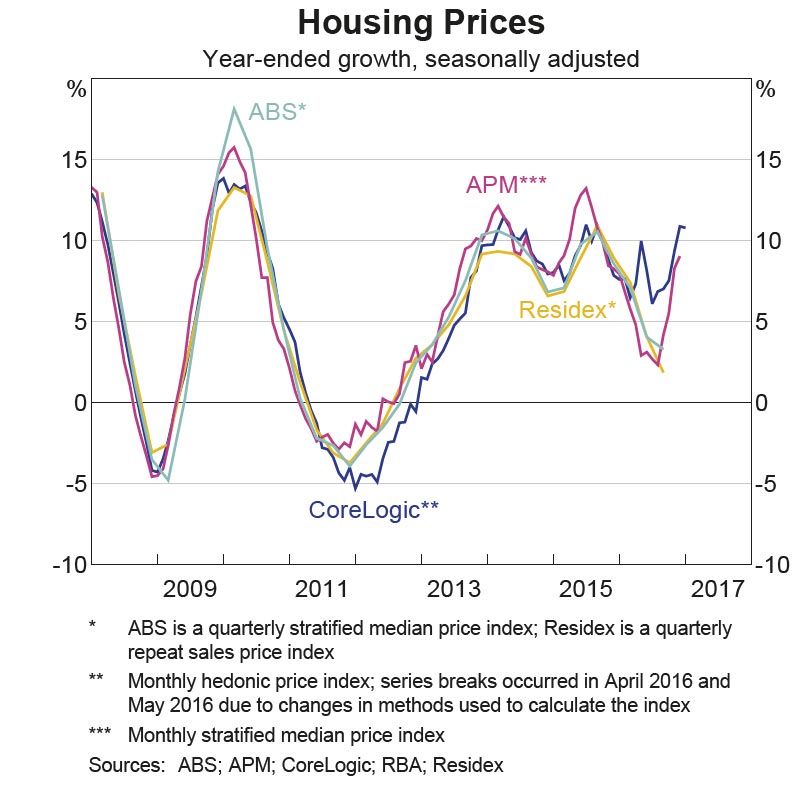

“This observation is signalling that the hurdle to even lower rates which would be aimed at boosting demand is very high,” he said. As house prices soared more than 65 per cent in Sydney in the past four years while floundering in other areas, some hedge funds and analysts have flagged overgeared households and a sagging real economy were increasing the risks of a housing correction.

US-based asset manager AllianceBernstein yesterday warned that potential “disorder” in the housing sector in the second half of next year clouded the outlook for Australia’s investment markets. Former Commonwealth Bank chief David Murray this month said all the signs of a housing “bubble” were prevalent, such as “people’s behaviour … and defensiveness about any correction”.

Mr Murray told Sky Business that investors owning multiple properties that were cross-collateralised who could become forced sellers were the “risk to the system”. But the big banks have repeatedly tried to ease fears about the risks, citing relatively low unemployment and most customers being ahead on their loan repayments.

Westpac last month reported actual mortgage losses after insurance eased to $31 million, or just 2 basis points of its loan book. The number of consumer properties in possession rose to 262, from 253 in March.

ANZ and Bank of Queensland, however, recently flagged concerns about stagnant wages, underemployment and the apartment glut in eastern cities.

According to DFA’s survey, around 80 per cent of households were travelling well and only 20 per cent were under stress, struggling to make repayments or having to cut back on spending.

Mr North said low wages growth and rising education and healthcare costs suggested borrowers’ financial situations would not improve. He predicted the banking industry’s loss rates would rise to about 4 basis points of mortgage loans, varying among lenders’ portfolios.

He said banks concentrated in troubled areas, such as WA, would be harder hit.

After the pick-up in bank stock prices since last month, CLSA analysts yesterday reminded investors that all were at risk of favourable loan-loss trends of recent years reversing and that CBA was more exposed than peers to WA.

WA has the largest proportion of stressed households at 26.4 per cent, just ahead of Victoria, but off a smaller population base, according to DFA’s survey.

Mr North said: “I’m theorising there is more risk in the mortgage book than I think the RBA recognises and more risk than some of the risk models used by the banks. It’s not dramatic … I’m not saying the world is caving in. 80 per cent of the book is fine.

“But it’s enough to at least be aware of.”