From The Conversation.

On September 18 2016, Glenn Stevens will end his ten-year mandate as governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). His experience in the top job provides a wealth of lessons for the next generation of policymakers; that’s arguably his most important legacy.

A graduate from the University of Sydney and the University of Western Ontario in Canada, Stevens worked in the RBA research department between 1980 and 1992. He then held positions as department head, assistant governor (economic) and deputy governor. In 2006, he was appointed governor.

A graduate from the University of Sydney and the University of Western Ontario in Canada, Stevens worked in the RBA research department between 1980 and 1992. He then held positions as department head, assistant governor (economic) and deputy governor. In 2006, he was appointed governor.

Throughout his tenure as governor, Stevens has had to deal with a highly volatile and generally fragile global economic and financial landscape. Domestically, he has been confronted with the end of the mining boom and a prolonged contraction of gross domestic product (GDP) below its potential level.

It is probably not an exaggeration to say that the ten years from 2006 to 2016 have been some of the most difficult economic times in post-war history. But it is exactly this highly complicated environment that provides a valuable learning opportunity for policymakers and for the economics profession more generally.

The monetary policy framework

The first lesson concerns the need for a “risk management” approach to monetary policy in a time of crisis.

The RBA’s monetary policy framework centres on an inflation target of 2%-3% on average over the medium term.

This means that actual inflation may deviate from the target in the short term in response to the cyclical conditions of the economy. For instance, when a negative demand shock reduces GDP below potential and causes unemployment to increase, reduced inflationary pressures allow the RBA to stimulate the economy by reducing the cash rate moderately.

In September 2008, when the global financial crisis hit the world, Australian inflation had been above target and on the rise for three consecutive quarters. This should have made the RBA prudent in cutting interest rates.

Instead, conditions worldwide were such that a change in monetary policy thinking was needed. The risks were simply too large to be treated with a normal policy approach.

Accordingly, the RBA moved to a “risk management” approach that, while broadly consistent with the flexible inflation-targeting framework, allowed for a quick (and much-needed) response.

As a result, the cash rate was reduced from 7.25% to 4.25% in the period September to December 2008 and then to 3% in the course of the first half of 2009. Comparatively, only the Bank of England cut its interest rate by as much as Australia.

The cut in the cash rate largely passed through to commercial lending rates, resulting in an increase in disposable income for many individuals. This then contributed (together with other factors, including the fiscal stimulus) to maintaining the Australian economy out of a recession.

It is highly likely that without this risk-management approach to monetary policy, Australia would have been much more severely affected by the global financial crisis.

The limits of monetary policy

The second lesson is that policymakers ought to be realistic and pragmatic about what monetary policy can and cannot deliver.

Through changes to the cash rate, monetary policy can affect the pace of real economic activity in the short term. But, in the long term, growth and unemployment are driven primarily by supply-side factors and monetary policy only affects inflation.

Moreover, the extent to which monetary policy can affect growth in the short term decreases as interest rates get lower. During the GFC, monetary policy effectively contributed to shielding the Australian economy because higher interest rates gave the RBA more room to cut.

But when interest rates are already low, the monetary policy space is reduced and further cuts are unlikely to produce significant effects.

Understanding the limits of monetary policy is particularly important in the current economic context.

The Australian economy has been operating below potential for several years now, as data from the International Monetary Fund suggests.

In response to this prolonged contraction, the RBA has reduced the interest rate to record low levels. It has reached the point where further cuts would probably be more damaging than beneficial.

Now more than ever recovery becomes a matter of fiscal policy interventions.

How to use monetary policy

The third lesson is about the use of monetary policy.

The inflation-targeting framework requires the RBA to set the cash rate having consideration for a variety of factors and data, including qualitative information received from conversations with businesses, investors and stakeholders.

In making the best possible use of these data and information, the RBA follows two guiding principles.

First, policy should not be driven by conclusions drawn from short runs of data. This then implies that the cash rate should not be fine-tuned continuously in response to marginal developments occurring month by month.

In normal circumstances, the interest rate ought to move gradually and rather infrequently to provide individuals (businesses and households) with some certainty about the course of monetary policy.

Second, monetary policy in Australia ought to be both outward- and forward-looking. An outward look is required because, as a small and open economy, Australia’s inflationary dynamics are heavily affected by developments on international markets.

This does not mean that the RBA should passively mimic the behaviour of other central banks. However, it does mean that the importance of international factors for the Australian economy should be adequately taken into account.

Forward-looking refers to the fact that forecasts ought to play a central role in the monetary policymaking process. To express this in Stevens’ own words:

After all, if monetary policy takes some time – several years – to have its full effect on the economy and inflation, forecasts have to be at the centre of things, don’t they?

Author: Fabrizio Carmignani, Professor, Griffith Business School, Griffith University

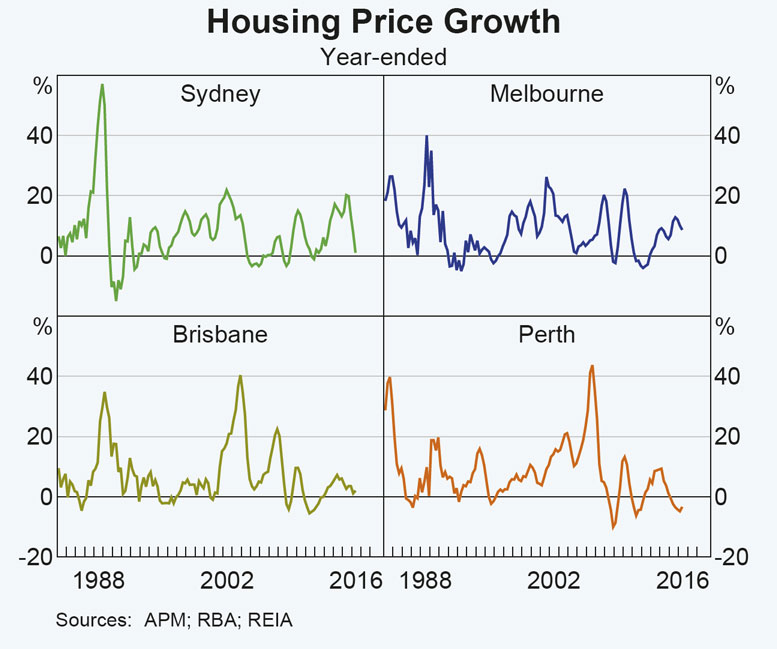

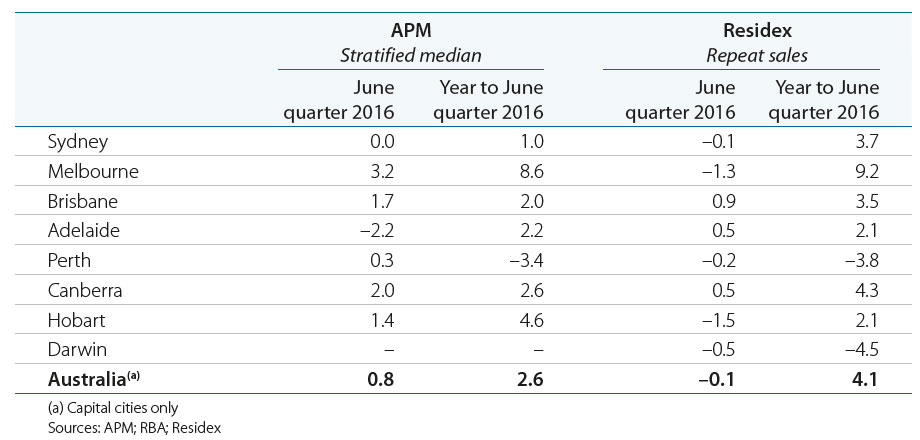

Now, we see there are some significant variations between the series, and of course in turn mask the significant differences between locations. CoreLogic has been tweaking their series, and the RBA specifically mentioned this in their recent report. These differences are driven by different methodologies, as well as some series breaks.

Now, we see there are some significant variations between the series, and of course in turn mask the significant differences between locations. CoreLogic has been tweaking their series, and the RBA specifically mentioned this in their recent report. These differences are driven by different methodologies, as well as some series breaks.