Companion cards

It has been just over a decade since the Bank first considered the case for regulating interchange-like payments made by American Express to its partner banks under companion card arrangements.

Since then, issuance of companion cards has grown faster than that for the four-party schemes, and the combined share of credit and charge card transactions accounted for by Diners Club and American Express has noticeably increased. The change largely occurred in two steps coinciding with the introduction of companion cards by the major banks. At the same time, evidence cited in our consultation paper points to a steady increase in the importance of companion cards within the overall American Express card business in Australia. Some merchants have indicated that an increased cardholder base as a result of companion card arrangements has increased the pressure for them to accept American Express cards.

For reasons that I have already outlined, differentials in interchange-like payments can have an important influence on the incentives to use particular payment methods, and these developments in companion card usage suggest that the different regulatory treatments for the two arrangements may have been a factor in shaping the development of the market. In the Bank’s view, an efficient payments system is promoted where the relative prices of different payment methods consistently reflect their relative resource costs.

In reviewing this area, the Bank has indicated that three options have been under consideration. Those options are to retain the current arrangements, to remove regulation of the four-party schemes, and to regulate interchange-like payments for companion cards so that they would be subject to the same cap as the four-party schemes. In its consultation paper released in December last year, the Bank indicated that it favoured the third of those options, and this has formed the basis for further consultation in the period since then.

Interchange fees

The interchange benchmarks set by the Board are the primary instrument for the Bank to anchor credit and debit card interchange fees at a desired level. The current benchmarks of 50 basis points for credit cards and 12 cents for debit have been in place since 2006. As I mentioned earlier, reductions in those benchmarks were considered, but not adopted, at the time of the 2007/08 review.

In the period since then, the Board has remained concerned that interchange benchmarks may still be higher in Australia than is desirable for payments system efficiency. Another concern has been the proliferation of interchange categories over time and the widening dispersion of interchange fees. Often these work to the disadvantage of smaller merchants who do not benefit from preferential strategic rates. As at September last year, the average credit card interchange rate faced by non-preferred merchants was 55 basis points higher than the rate faced by preferred merchants; for debit cards the difference was around 13 cents. At the individual merchant level, these differences can be much bigger.

In its December consultation paper the Bank set out a series of regulatory options in this area. They included retaining the status quo, reducing the weighted average benchmarks, and supplementing those benchmarks with hard caps on individual transactions. A fourth option of removing interchange regulations, while strengthening transparency of these fees to merchants, was also included. The Board’s preliminary assessment was in favour of a mix of the second and third options I just described. This would involve retaining the existing weighted average of 50 basis points for credit cards, supplementing it with a hard cap of 80 basis points on individual transactions, and reducing the debit benchmark to 8 cents. Once again, this was not a final decision but was announced as a basis for the subsequent phase of consultation that is now being completed.

As well as looking at the overall level of interchange fees, the Review is also considering a number of related issues concerning coverage and compliance.

On coverage, the issues discussed in the December paper concern commercial cards, foreign-issued cards and pre-paid cards. Currently commercial cards are included within the scope of the Bank’s interchange standards and hence form part of the calculation for the purposes of compliance with the weighted average benchmark. A number of interested parties have argued that these cards should be exempted, especially in the event that interchange caps were lowered. They argue, for example, that commercial cards typically provide a higher value of associated services than other card types, with fewer non-interchange revenue streams, and that these features could justify higher fees. On the other hand, consultations also suggest that these cards provide significant benefits to both sides of the market, and hence it is not clear that higher interchange fees are needed to promote their use. The Bank has also noted that, since commercial cards typically carry higher interchange fees than consumer cards, their exemption would amount to a de facto loosening of the weighted average cap.

Foreign-issued cards are currently excluded from the benchmark calculations, and the question is whether these should be brought within the scope of domestic regulation for transactions acquired in Australia. Here a key consideration is the possibility of circumvention. Foreign-issued cards used in Australia typically carry a much higher interchange fee than the domestic benchmark, and under current arrangements could be used to circumvent the domestic cap. At this stage, however, the market share of foreign issued cards in Australian card transactions is still relatively small – around 3 per cent. In response to the December consultation document, Mastercard and Visa (among others) have made a number of arguments for retaining the existing treatment of foreign-issued cards, and these are being carefully considered.

For domestic pre-paid cards, the Board is similarly considering whether these should be brought within the scope of the existing standard.

The issue concerning the compliance mechanism can be stated fairly simply. The current mechanism operates on a three-year compliance cycle, such that the weighted average benchmark has to be met in November of every third year. Since the mix of card transactions within any system tends to shift towards the higher cost cards over time, average interchange fees have tended to rise during each three-year period. This in turn has had the paradoxical effect that the actual weighted averages for the Visa and Mastercard schemes have been almost always above the cap. The Board’s intent, however, is that average fees should be below the cap, not above it. That is what a cap means. The review process is consulting on options to tighten the compliance mechanism in keeping with that intent.

A related question on compliance concerns the possible regulation of scheme payments to issuers. These marketing and incentive payments are bilaterally negotiated and can be quite material in value, and the flexibility of such payments means that they can be structured in ways to circumvent interchange regulation. Internationally, regulators have moved to limit these types of payments. Under European regulation, for example, they are treated as if they were interchange payments. As part of its Review, the Board is considering whether a similar treatment should be adopted here. The preliminary position announced in December was in favour of that option.

Surcharging

As I have already mentioned, the Board has long held the view that the ability to surcharge for more expensive payment methods is part of an efficient payment system. The ability to surcharge expands the options available to merchants beyond a binary decision to accept or reject a card, and it allows price signals to pass through to the consumer who decides which payment method to use.

Nonetheless, efficient surcharging should reflect the cost to the merchant. When the Board’s initial surcharging reforms were put in place in 2003 it was expected that market forces would provide a sufficient discipline on surcharging behaviour. Since then, however, evidence of excessive surcharging in some industries has accumulated.

The Board revised its regulation in 2013 to give schemes greater power to prevent excessive surcharging, but those arrangements proved difficult to enforce. This has prompted a further review by the Board as part of its current process. As well as consulting with the full range of interested stakeholders, the Bank has had discussions with the ACCC and Treasury about possible policy approaches. The Board’s proposed response builds on the recent Government measures to strengthen ACCC enforcement powers in this area.

The main elements of the coordinated approach were set out in the December consultation paper. These are, that:

- Government legislation bans excessive surcharging, defined as surcharging in excess of the Reserve Bank standard

- The Bank’s standard is based on a simple and verifiable measure of the cost of acceptance, with appropriate transparency of costs to merchants

- The ACCC has enforcement powers in cases of excessive surcharging by merchants, and

- The Bank’s standard continues to stipulate that schemes may not have no-surcharge rules.

Under the Bank’s preferred approach, acquirers would be required to provide merchants with regular statements of the cost of acceptance for each payment method. The cost of acceptance would have to be expressed in percentage terms unless the acquirer fees for that payment method were fixed across all transaction values. As a result, surcharging would normally also have to be percentage based. Among other things, this would rule out the current system of fixed-dollar surcharges in the airline industry, which would appear to result in significant over-recovery of payment costs on low-value fares.

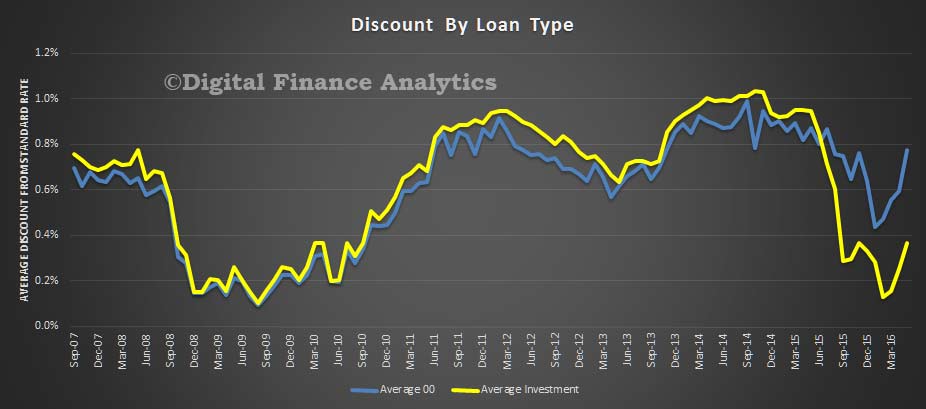

We are also seeing some relaxing of lending standards now, as banks chase investor loans well below 10% growth rates, and continue to offer cut price loans for refinance purposes. Average discounts on both investment loan have doubled.

We are also seeing some relaxing of lending standards now, as banks chase investor loans well below 10% growth rates, and continue to offer cut price loans for refinance purposes. Average discounts on both investment loan have doubled.