The Board’s discussion about economic conditions opened with the observation that economic growth in Australia’s major trading partners appeared to have been around average in the June quarter. Consumption growth had been little changed for most trading partners in recent months, although it was perhaps a bit stronger in the United States and somewhat weaker in China. The level of consumption in Japan remained well below that seen prior to the increase in the consumption tax in 2014. Core inflation rates had been stable in year-ended terms over recent months and remained below the targets of most central banks. Members also observed that trade volumes, particularly within the Asian region, appeared to have fallen recently. Consistent with this observation, growth in industrial production across a number of east Asian economies had slowed a little.

In China, there had been little change in the monthly indicators of economic activity, although conditions had been a bit more positive in some sectors than early in 2015. The Chinese property market had improved somewhat; residential property prices overall had risen for the first time in a year and floor space sold had increased in the past few months. Members reflected that the recent easing in monetary conditions would provide additional support to the property market and growth more broadly, although it could be some time before a significant pick-up in construction activity began. Recent efforts by central government authorities to increase infrastructure investment further and reform local government financing arrangements were also expected to support investment.

Commodity prices overall had fallen since the previous meeting, driven by iron ore and oil prices. Growth in crude steel production had been modest and steel prices had fallen noticeably over the past month. Iron ore production in China had continued to decline. Shipments of iron ore from Australia and Brazil appeared to have increased in June, which contributed to lower iron ore prices over the past month.

Following quite strong output growth in Japan in the March quarter, more timely indicators pointed to modest growth in the June quarter. Labour market conditions had continued to improve, resulting in the unemployment rate falling further and the ratio of jobs to applicants continuing to rise. Wage growth and financial market measures of inflation expectations were higher than a year earlier and were expected to feed into higher core inflation over time. Members considered the importance for Japan of policy reforms designed to address some longer-term structural challenges, such as the ageing of the population.

In the United States, recent data pointed to moderate growth in economic activity in the June quarter following weakness in the March quarter. The labour market had strengthened further, with growth in non-farm payrolls employment rebounding in April and May and the unemployment rate falling. While there had been some increase in measures of wage growth, core measures of inflation remained below the Federal Reserve’s inflation target.

In the euro area, the available indicators pointed to modest economic growth and above-average sentiment in the June quarter, continuing the recent trend of improved conditions in the euro area as a whole. Members noted that exports had made a significant contribution to the pick-up in growth in the region but investment was still well below the levels seen prior to the global financial crisis. The unemployment rate had continued to fall modestly since its peak two years earlier, but varied sharply across the euro area; the unemployment rate was highest in Greece, where output was more than 25 per cent below its level prior to the financial crisis.

Domestic Economic Conditions

Members noted that output had increased by 0.9 per cent in the March quarter and by 2.3 per cent over the year. Resource exports had made a significant contribution to growth, reflecting better-than-usual weather conditions in the quarter. Dwelling investment had remained strong and while consumption growth had picked up over the past year or so, it had remained below average. Business investment had contracted in the quarter and there had been little growth in public demand. More recent economic indicators suggested that domestic demand had continued to grow at a below-average pace over recent months, but that labour market conditions had continued to improve.

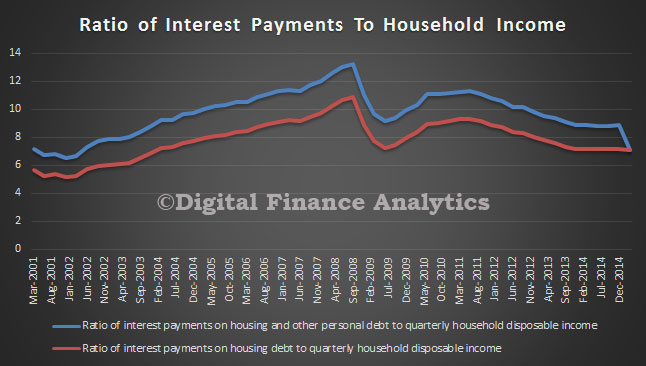

Members observed that consumption grew faster than household income over the year to the March quarter. As a result, the saving ratio had declined further, although it remained well above the level it had been over much of the past 25 years. Year-ended growth in retail sales had been little changed over recent months and liaison suggested that this was likely to have continued into June. Retail sales growth had been relatively strong in New South Wales and Victoria but weaker in Queensland and Western Australia, in line with observed differences in economic conditions across the country. At the same time, surveys indicated that consumers had viewed their financial situation as being above average over the past year, notwithstanding the relatively weak growth in labour incomes. Members observed that this was likely to reflect the very low level of interest rates and strong growth in net household wealth.

Dwelling investment increased by 9 per cent over the year to the March quarter. An increase in the construction of new dwellings accounted for most of this growth, but the alterations and additions component had also contributed more recently, recording the first increase in a year in the March quarter. Forward-looking indicators pointed to further strong growth in dwelling investment in the period ahead. Members noted that there had been ongoing divergence in conditions in established housing markets across the country, as well as between houses and apartments. Housing prices had continued to rise rapidly in Sydney and to a lesser extent in Melbourne. Elsewhere, there had been little change in housing prices over the past six months or so. Prices of apartments had been growing less rapidly than those of houses, which members considered to be consistent with the relatively strong growth in the supply of higher-density housing in many capital cities.

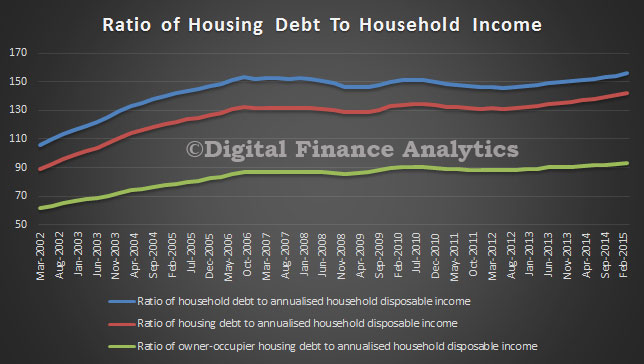

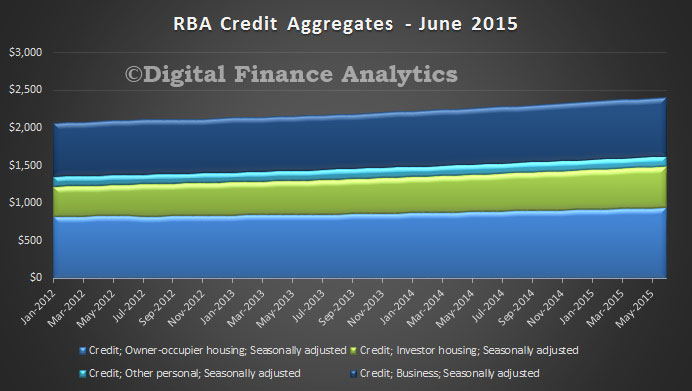

Growth in housing credit overall had been stable over recent months at around 7 per cent on an annualised basis, while growth in lending to investors had been steady at a bit above 10 per cent. Members observed that the household debt-to-income ratio, calculated by netting funds held in mortgage offset accounts from total household debt to the financial sector, had increased over the year to March but had not exceeded previous peaks. Members discussed the fact that high housing prices had different implications for existing home owners, who benefited from increased wealth, and potential new home owners, who were finding it more difficult to finance a home purchase.

Investment in both the mining and non-mining sectors appeared to have fallen in the March quarter, although the split between the two components remained subject to some uncertainty. Profits for non-mining firms had increased by 6 per cent over the past year. More recent survey measures of business conditions, confidence and capacity utilisation had picked up to be around, or even above, their long-run averages. In contrast, private non-residential building approvals had remained weak.

The monthly trade data suggested that resource exports, including iron ore and coal, had declined in the June quarter. Coal exports had been affected by the severe storms in the Hunter region of New South Wales in late April. Members noted that there had been further signs of growth in service exports, in part a response to the depreciation of the exchange rate. Over the past year, net service exports had made a similar contribution to output growth as exports of iron ore, even though total import volumes had increased in the March quarter.

Labour force data indicated further signs of improvement in May. Employment growth had picked up over the year to exceed the rate of population growth. As a result, the unemployment rate had been relatively stable since the latter part of 2014 and had fallen slightly in May to 6 per cent. Members observed that employment growth had been strongest in household services and that employment and vacancies had been growing for business services but had remained little changed in the goods sector. As with other state-based indicators, employment growth and job vacancies had been strongest in New South Wales and Victoria. Forward-looking labour market indicators had been somewhat mixed over recent months. The ABS measure of firms’ job vacancies overall suggested that demand for labour could be sufficient to maintain a stable or even falling unemployment rate in the near term, while other forward-looking indicators suggested only modest growth in employment in coming months.

Members noted that the latest estimates indicated that the population had increased by 1.4 per cent over the year to the December quarter, down from a peak rate of growth of 1.8 per cent over 2012. The slower growth was primarily accounted for by a decline in net immigration, which was particularly pronounced in Western Australia and Queensland, consistent with weaker economic conditions in those states. Members observed that the lower-than-expected growth in the population helped to reconcile the below-average growth in output over the past year with a broadly steady unemployment rate.

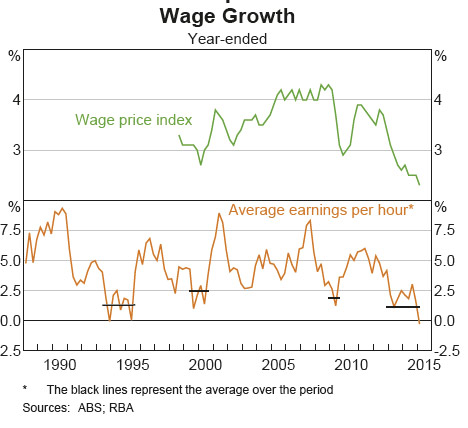

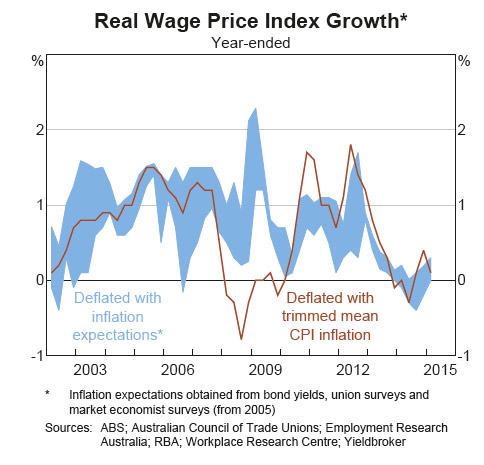

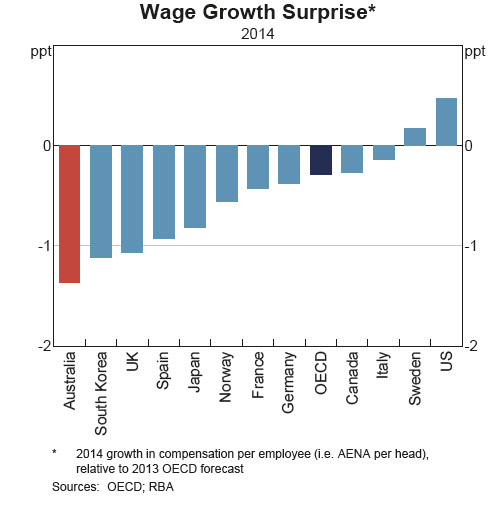

Despite recent improvements in labour market indicators, members reflected that there was still evidence of spare capacity in the labour market. Consistent with this, the latest national accounts data indicated that non-farm average earnings per hour had recorded the lowest year-ended outcomes since the early 1990s and that unit labour costs had been little changed for around four years.

Financial Markets

International financial markets were mainly focused on developments in Greece and the fall in Chinese equity markets over the past month.

Members were briefed on recent developments in Greece. The ‘no’ vote in the referendum on the creditors’ latest proposals raised several issues, first among which was how the Greek authorities could reopen the banks. A critical vulnerability in the near term was related to whether the European Central Bank would provide additional emergency liquidity assistance. A second issue was how Greece would be able to service its external debt and a third was the challenges faced by the Greek authorities in improving the competitive position of the economy. Although these issues were of great concern to the Greek populace, the direct economic implications for the global economy and Australia were assessed by members to be relatively limited. They noted that the reaction of financial markets to these developments had been fairly muted. This was consistent with the economic and financial exposures to Greece – apart from the official sector’s financial exposure – being quite low.

Members noted that spreads to 10-year German Bunds on comparable bonds issued by Italy, Spain and Portugal had not risen much, with the limited contagion from developments in Greece likely to have reflected a general view of markets that previous adjustment policies in those countries had been relatively successful.

Members then turned their discussion to developments in bond markets more generally. Yields on longer-maturity German Bunds and US Treasuries had risen sharply over the first half of June, with German 10-year yields reaching 1 per cent, compared with a historic low of 8 basis points in mid April. German yields declined somewhat following the announcement of the Greek referendum. Longer-term sovereign yields of most other developed countries, including Australia, tended to move in line with US Treasuries.

Expectations about the timing of the US Federal Reserve’s first increase in the federal funds rate were little changed over the past month. Market pricing continued to suggest that the first increase would occur around the end of 2015. Although commentary by Federal Reserve officials suggested that it could be a little sooner than that, they continued to emphasise that the exact timing of the first increase would be less important than the pace of subsequent increases, which were expected to be gradual.

The People’s Bank of China (PBC) eased monetary policy further in June by cutting benchmark deposit and lending rates by 25 basis points, citing low inflation and a consequent increase in real interest rates. In addition, the PBC announced cuts to the reserve requirement ratio for selected financial institutions. The Chinese authorities had also announced a proposal to allow banks more flexibility in their choice of funding mix and asset allocation, which could lead to an increase in the supply of credit over time.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand lowered its policy rate by 25 basis points, to 3.25 per cent, citing the decline in New Zealand’s terms of trade and the disinflationary effect of stronger-than-expected labour force growth.

Global equity markets fell by 3 per cent over the course of June, with broad-based falls and price movements generally tending to reflect fluctuations in sentiment about Greece. The Chinese equity market also fell sharply in June, partly in response to what was only a modest tightening of restrictions on margin lending. Mainland share prices were still well above their levels of a year earlier but the sharpness of the recent fall prompted the Chinese authorities to announce a number of measures, including an indefinite suspension of initial public offerings, an equity stabilisation fund and a funding facility for brokers. The Australian equity market underperformed several other advanced economy markets in June, mainly reflecting falls in resources and consumer sector share prices.

Global foreign exchange markets were relatively subdued in June. The euro recorded only a modest and short-lived fall when markets opened after the announcement of the Greek referendum result. The Australian dollar was 3 per cent lower against the US dollar and on a trade-weighted basis.

Corporate bond issuance in Australia had been strong over the course of 2015 to date, particularly by resource companies, although much of the increase reflected refinancing.

Pricing of Australian money market instruments suggested that the cash rate target was expected to remain unchanged at the present meeting.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

Members noted that global economic conditions remained consistent with growth in Australia’s major trading partners being around average over the period ahead. Global financial conditions were very accommodative and would remain so even in the event that the Federal Reserve started to raise its policy interest rate later in the year. Recent data suggested that conditions in Chinese property markets had improved and the authorities had acted to support activity by easing a range of policies further. Members noted that the recent volatility in Chinese equity markets and potential spillovers from developments in Greece would require close monitoring.

Domestically, the key forces shaping the economy over the past year were much as they had been for some time. Very low interest rates were working to support strong growth in dwelling investment and, together with strong housing prices, had supported consumption growth. Resource exports had made a substantial contribution to growth and mining investment had declined significantly, while public demand had been flat over the past year. Although output growth in the March quarter had been stronger than expected, growth over the year remained below average and early indications were that the strength in the March quarter had not carried through to the June quarter. Non-mining business investment had been subdued and surveys of businesses’ investment intentions suggested that it would remain so over the coming year. Nevertheless, non-mining business profits had increased over the past year and surveys suggested that business conditions had generally improved over recent months to be a bit above average.

Conditions in the housing market had been little changed in the most recent months, with notable strength in Sydney. Housing credit growth had been steady and remained relatively strong for investors in housing, although it had not accelerated. Any effects of regulators’ greater scrutiny of investor lending were probably not yet evident in the data.

Recent data indicated that employment had grown more rapidly than the population and the unemployment rate had been relatively stable since the latter part of the previous year. The easing in population growth over the past year helped to reconcile below-average growth in output with the relatively steady unemployment rate. Nevertheless, spare capacity remained, as evidenced by the level of the unemployment rate, historically low wage growth and unit labour costs that had been stable for a number of years. On this basis, members assessed that inflationary pressures were well contained and likely to remain so in the period ahead.

Commodity prices had fallen further and the Australian dollar had depreciated over the past month. Although the exchange rate against the US dollar was close to levels last seen in 2009, the decline in the Australian dollar had been more modest in terms of a basket of currencies. Members noted that the exchange rate had thus far offered less assistance than would normally be expected in achieving balanced growth in the economy and that further depreciation seemed both likely and necessary.

In light of current and prospective economic circumstances and financial conditions, the Board judged that leaving the cash rate unchanged was appropriate. Information to be received over the period ahead on economic and financial conditions would continue to inform the Board’s assessment of the outlook and hence whether the current stance of policy remained appropriate to foster sustainable growth and inflation consistent with the target.

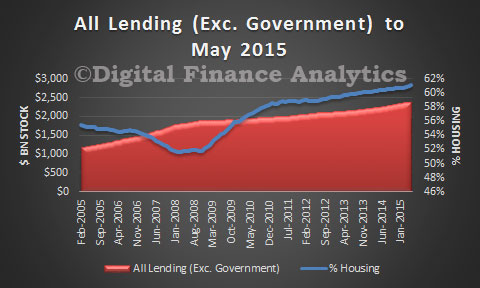

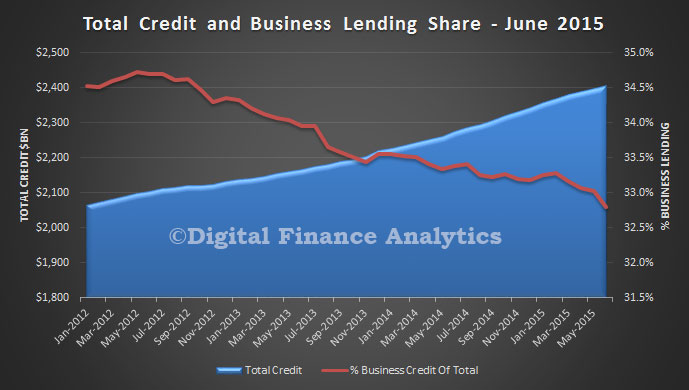

Total lending to business as a share of all lending fell again to 32.8%, this is not healthy as productive growth comes from business investing in their futures. This is not as strong as we need to sustain the economy.

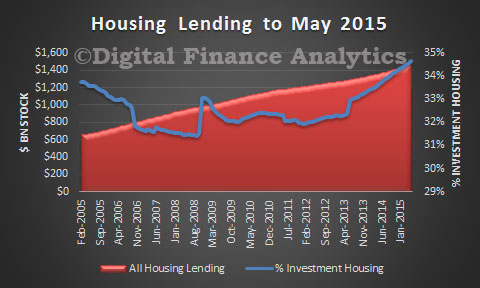

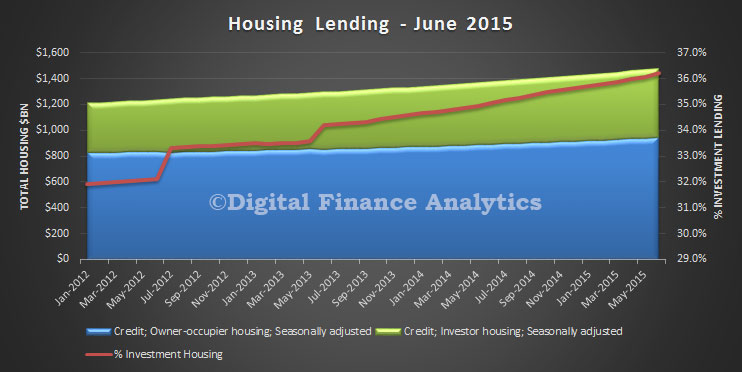

Total lending to business as a share of all lending fell again to 32.8%, this is not healthy as productive growth comes from business investing in their futures. This is not as strong as we need to sustain the economy. Looking at the mix of lending for housing, investment lending was up to 36.2%. It has never been higher. This inflates house prices, and banks balance sheets, but the wealth is artificial, and unproductive.

Looking at the mix of lending for housing, investment lending was up to 36.2%. It has never been higher. This inflates house prices, and banks balance sheets, but the wealth is artificial, and unproductive. Finally we think there are some funnies in these numbers, which when we have completed the analysis of the APRA monthly banking statistics, we will comment on further. Suffice it to say, it seems maybe some loans were reclassified last month from owner occupied to investor loans, so might be distorting the data.

Finally we think there are some funnies in these numbers, which when we have completed the analysis of the APRA monthly banking statistics, we will comment on further. Suffice it to say, it seems maybe some loans were reclassified last month from owner occupied to investor loans, so might be distorting the data.