International Economic Conditions

Members noted that growth of Australia’s major trading partners had continued at around its average pace in early 2015. Growth in China looked to have eased a little further and this was likely to have contributed to further declines in iron ore and coal prices. Globally, the fall in oil prices in the second half of 2014 had led to lower inflation and was expected to provide additional support to demand in Australia’s trading partners. Monetary policies remained very accommodative.

In China, the authorities had announced a target for GDP growth in 2015 of 7 per cent, ½ percentage point below the target for 2014. Recent indicators suggested that economic conditions had softened. Growth of fixed asset investment had been slowing, particularly in real estate and manufacturing, and prices of residential property and sales volumes had declined further. Members noted that the deterioration in conditions in the property market had increased the vulnerability of leveraged property developers and local authorities that relied on revenue from land sales to support their infrastructure investment. They also noted that the central authorities had indicated a willingness to adjust policies to support employment growth, while remaining committed to putting financing on a more sustainable footing. The weakness in the property market in China had flowed through to slower growth in the demand for steel, which had, in turn, contributed to the recent falls in iron ore prices, even though Chinese imports of Australian iron ore had continued to increase.

The modest recovery of the Japanese economy was continuing. Labour market conditions remained tight and the recent annual spring wage negotiations had resulted in several large companies increasing base wages by more than they did a year earlier. In the rest of the Asia-Pacific region, growth had continued at around its average pace of the past decade, although there had been variation in the composition of growth across the region.

Members observed that the US economy had continued to grow, but that the pace of growth may have moderated in the early months of this year partly in response to the temporary effects of adverse weather conditions and industrial action at some ports. Labour market conditions had strengthened further over the past six months or so; employment had increased at around its fastest pace in several years and the unemployment rate had declined further. Members noted that overall wage growth in the United States remained subdued. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had indicated that it was likely to begin the process of normalising interest rates in the second half of this year if economic conditions continued to evolve as expected.

In the euro area, economic activity had continued to recover gradually. The unemployment rate had declined a little further and there had been a noticeable lift in activity in some euro area periphery economies. Lower oil prices had reduced consumer price inflation significantly, but core measures of consumer price inflation had not changed much in recent months and remained well below the target of the European Central Bank (ECB). There had been some signs that conditions in the construction sector had stabilised and credit to both households and businesses was increasing, albeit gradually.

Members observed that bulk commodity prices had declined further over the past month. Although much of the decline over 2014 was driven by expansion in global supply, the slowing in growth of Chinese demand had contributed more recently. A small (but increasing) share of Australian iron ore production was estimated to be unprofitable at prevailing prices, while the decline in oil prices since the middle of 2014 was expected to lower the prices of Australian liquefied natural gas exports over the next few months.

Domestic Economic Conditions

The December quarter national accounts, which were released the day after the March meeting, confirmed that the Australian economy had grown at a below-average pace over 2014. Members noted that growth in dwelling investment, consumption and resource exports had picked up, but that business investment had continued to fall and public demand had made little contribution to growth over the year. Recent indicators suggested that the below-trend pace of GDP growth had continued into the March quarter.

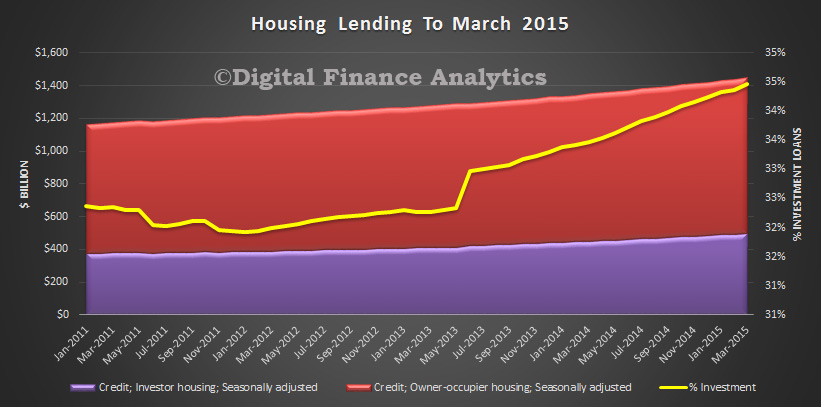

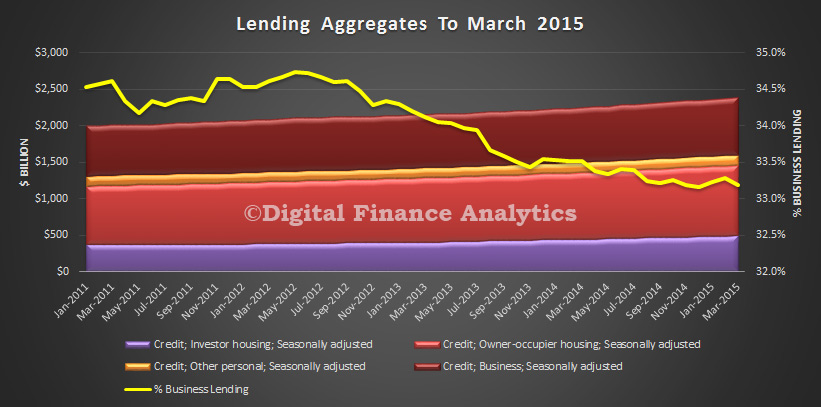

Overall conditions in the housing market had remained strong, supported by very low interest rates and relatively strong population growth. Housing prices had continued to rise strongly in Sydney and, to a lesser extent, Melbourne, but growth in prices had eased recently in some other parts of the country. Other indicators of activity had also suggested strong conditions in the established housing market in Sydney and Melbourne. Housing credit overall had been growing at about 7 per cent in six-month-ended annualised terms, while credit to investors had grown at a pace a little above 10 per cent on the same basis. Recent data on loan approvals suggested that growth in housing credit was likely to continue at this pace, but not accelerate, in the months immediately ahead. Meanwhile, new dwelling approvals and loan approvals for new construction were at high levels, pointing to strong growth in dwelling investment over coming quarters.

Household consumption had increased in the December quarter, supported by low interest rates and rising household wealth. Even so, growth in household consumption over the second half of 2014 had been slightly below average, reflecting subdued growth in household income, while the saving ratio had continued its gradual decline of the past two years. More timely data had indicated that growth in the value of retail trade in January and February was about average and that consumer confidence had been close to average levels.

Mining investment was estimated to have declined by 13 per cent over 2014 and an even larger decline was expected over 2015. Moreover, members observed that the recent declines in oil prices could lead to some scaling back of investment plans in the oil and gas sector. Non-mining investment had been subdued for some time. Forward-looking indicators (such as the ABS capital expenditure survey and non-residential building approvals) as well as liaison suggested that it was likely to remain subdued, and could even decline, over the next year or so. Members noted, however, that there had been a pick-up in growth of credit to businesses of late. They also observed that the strongest improvement in investment intentions (apparent in the recent capital expenditure survey) had been recorded for industries experiencing the strongest output growth, such as rental, hiring & real estate and retail trade. More recently, survey measures of business confidence and capacity utilisation remained a little below average, while measures of business conditions were around average levels.

Members observed that there had been significant variation in the composition of domestic demand growth across the states over the course of 2014. Dwelling investment and consumption had contributed to growth in all states, whereas business investment had subtracted from growth in Queensland and Western Australia, mainly reflecting the decline in mining investment in these states. Members noted that public demand had contributed to domestic demand growth only in New South Wales and Victoria over the year and had made no contribution to output growth for the country as a whole.

Resource exports had grown strongly in the December quarter and there were early indications of strength in resource exports in the first few months of 2015. However, lower commodity prices were expected to lead to some reduction in the growth of production, and therefore exports, in 2015, particularly for coal. The data for recent quarters were consistent with the lower exchange rate having provided support to net exports, particularly for services.

Recent employment growth had been stronger than a year earlier, but it was still below the growth of the working-age population. Consequently, the unemployment rate had continued its gradual upward trend of recent years, notwithstanding a modest decline in February to 6.3 per cent. Other indicators, such as hours worked and the participation rate, had provided further evidence of spare capacity in the labour market. The various forward-looking indicators were stronger than a year earlier, but remained at levels consistent with only modest employment growth in the months ahead.

Members noted that the national accounts measures of wage growth had remained subdued. Combined with some pick‑up in labour productivity growth over recent years, this had meant that unit labour costs had not changed much for about three years. Various measures of inflation expectations had remained slightly below their longer-run averages.

Financial Markets

The Board’s discussion of financial markets commenced with the unusual trading in the Australian dollar that occurred in the period immediately prior to the announcement of the Board’s decisions in both February and March. Members noted that the illiquid conditions that existed in the foreign exchange market at that time meant that small trades could move the price by relatively large amounts, and that once such movements occurred it would be highly likely that algorithmic trading strategies would exacerbate such movements, particularly given the illiquid environment. Moreover, the occurrence of these movements meant that liquidity was likely to decline further as more liquidity providers pulled back from the market during this window.

Members were aware of the investigations currently being undertaken by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and were informed that internal work since the March meeting had not identified any evidence of procedural lapses or conduct that could have led to the early release of relevant information.

Global financial markets over the past month had continued to focus on the expected path of US monetary policy as well as the strained relationship between the Greek Government and its creditors.

Members noted that projections by members of the FOMC for the path of the federal funds rate had been revised down at the FOMC’s March meeting. Those projections remained above market expectations, which had flattened further following the FOMC’s reassessment and again after the release of weaker-than-expected employment data for March. Markets expected the first rise in the US federal funds rate to occur towards the end of the year.

Members also noted that negotiations between the new Greek Government and the European Commission, the ECB and the International Monetary Fund were fraught. As a result, there was some risk that Greece would not receive assistance funds in a timely fashion and the government would continue to rely on emergency measures to cover its liquidity needs. Greek banks in particular continued to face deposit outflows and had lost access to private funding markets, and as a result had increased their reliance on ECB funding. On a more positive note, members observed that there continued to be little contagion to other euro area periphery countries.

Members were briefed about the ECB’s balance sheet expansion in March, mainly reflecting lending to banks under its latest targeted longer-term refinancing operation and the commencement of government bond purchases. The ECB had also announced in March that it would not purchase bonds that carried yields below the rate that it paid on deposits (at present –0.2 per cent), indicating that the ECB would need to buy relatively long-dated German Bunds.

Government bond yields in most of the major economies remained at very low levels. They had shown little net change in the United States and Japan, while yields on long-term German Bunds had declined further following the launch of the ECB’s sovereign bond purchasing program. Domestically, longer-term government bond yields had also declined and the 10-year Australian bond yield was around its record low, with the spread to US yields close to its lowest level since 2001.

There were sizeable rises in equity prices in European and Japanese markets in March, while equity prices in China had increased by 15 per cent over the past month and by 90 per cent since the middle of 2014. In contrast, equity prices in Australia had been little changed in March. Prices of resource stocks remained under pressure.

The US dollar had appreciated a little further on a trade-weighted basis over March, taking the rise since July 2014 to 14 per cent. Over the same period, members observed that both the euro and the Australian dollar had depreciated by around 20 per cent against the US dollar. While the renminbi had both appreciated and depreciated at different times since July 2014, these moves had roughly netted out against the US dollar overall and the renminbi had therefore appreciated noticeably against most other currencies. Members also noted that the Australian dollar had recorded an all-time low against the New Zealand dollar.

Members concluded their discussion of financial markets with the observations that lending rates for business and housing in Australia had continued to edge down over the previous month, and that financial markets assigned a high probability to a reduction in the cash rate at the current meeting, and an even higher probability to a reduction occurring by the May meeting.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

Members’ overall assessment was that the outlook for global economic growth had not changed significantly over the past month and that it would be supported by stimulatory monetary policies and the fall in the price of oil since mid 2014. They observed that the apparent slowing of growth in China, in particular the further deterioration in conditions in the Chinese property market, had placed some additional downward pressure on the demand for steel and on the prices of Australia’s key commodity exports. Conditions in global financial markets had remained very accommodative. Changes to the stance of monetary policy by any of the major central banks and further significant developments in Europe had the potential to affect financial market conditions in Australia, including the exchange rate, over the coming year.

Data available at the time of the meeting suggested that the Australian economy had continued to grow somewhat below trend in the December quarter and into the first quarter of 2015. There had been evidence to suggest that the growth in consumption and dwelling investment had picked up, supported by the very low levels of interest rates. Exports were also growing. However, a significant pick-up in non-mining business investment was yet to occur and several indicators suggested it would remain subdued for longer than had earlier been anticipated. At the same time, the recent declines in bulk commodity prices could, at the margin, lead to a larger-than-expected fall in mining investment and some decline in the production of iron ore and coal. Data for the labour market suggested that the economy was likely to be operating with a degree of spare capacity for some time and that labour market conditions were likely to remain subdued. As a result, wage pressures were expected to remain contained and inflation was forecast to remain consistent with the target over the next year or so.

Members remained alert to the possibility that the low levels of interest rates could foster imbalances in the housing market. The most recent data suggested that activity in the housing market had remained strong, but there had been little change to housing market conditions overall or in the growth of housing credit in early 2015. Although prices continued to rise rapidly in Sydney and, to a lesser extent, Melbourne, trends elsewhere were more varied. Members noted that the Bank was working with other regulators to assess and contain risks arising from the housing market.

Overall, members considered that the current setting of monetary policy was accommodative and providing support to the economy. They also acknowledged that a lower exchange rate would help achieve more balanced growth in the economy. Further depreciation of the Australian dollar was likely given the recent declines in key commodity prices.

In considering whether or not to reduce the cash rate further at this meeting, members discussed the various channels through which monetary policy was affecting the economy at present, including the asset price and exchange rate channels. In assessing the operation of the cash flow channel in particular, they noted that the responsiveness of borrowers and savers to changes in interest rates and asset prices was unusually uncertain in a world of very low interest rates and high household leverage. Members also saw advantages in receiving more data, including on inflation, to assess whether or not the economy was on the previously forecast path and allowing more time for the economy to respond to the reduction in the cash rate earlier in the year.

Taking all these factors into account, the Board judged that it was appropriate to hold interest rates steady for the time being, while accepting that further easing of policy may be appropriate over the period ahead to foster sustainable growth in demand and inflation consistent with the target. The Board would continue to assess the case for such action at forthcoming meetings.

The Decision

The Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 2.25 per cent.