Based on this conclusion, we think the globalisation of inflation drivers have relevance in other markets too, and makes domestic management of inflation via monetary policy much more difficult. Taking the cash rate lower rates won’t cure it.

In recent years, inflation has been low – and below the rate targeted – in many advanced countries around the world. The possible reasons for this are a focus of discussion for central bankers, financial market participants, politicians, academics and journalists, both here and abroad. Low inflation in New Zealand is what I want to talk to you about today.

The consumer price index (CPI) for the September quarter will be released next Tuesday, and it is widely expected to reveal continued low inflation. The Bank’s goal is to keep future annual CPI inflation outcomes between 1 percent and 3 percent on average over the medium term, with a focus on keeping future average inflation near the 2 percent target midpoint. As described in the September Official Cash Rate (OCR) review, monetary policy will continue to be accommodative. Interest rates are at multi-decade lows, and our current projections and assumptions indicate that further policy easing will be required to ensure that future inflation settles near the middle of the target range.

The Reserve Bank’s forecast in the August Monetary Policy Statement was for annual headline CPI inflation to be 0.2 percent in the September quarter. More recent information, including movements in petrol and food prices, remains consistent with this low number. Our typical margin of error in forecasting near-term annual CPI inflation is about 0.2 percentage points. So, while we have no prior knowledge, next week’s outturn could be between zero and half a percent.

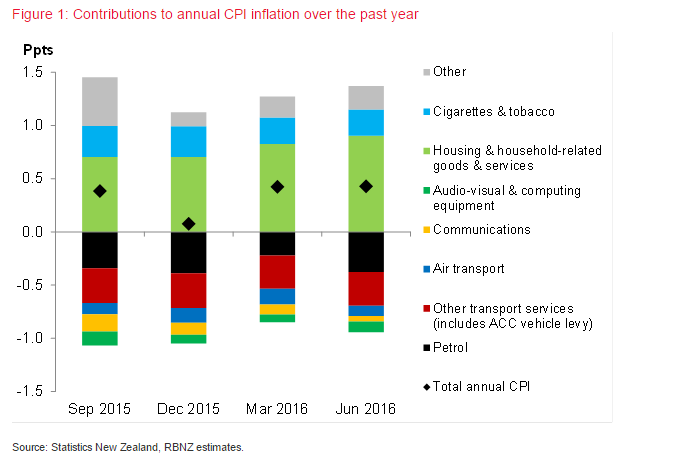

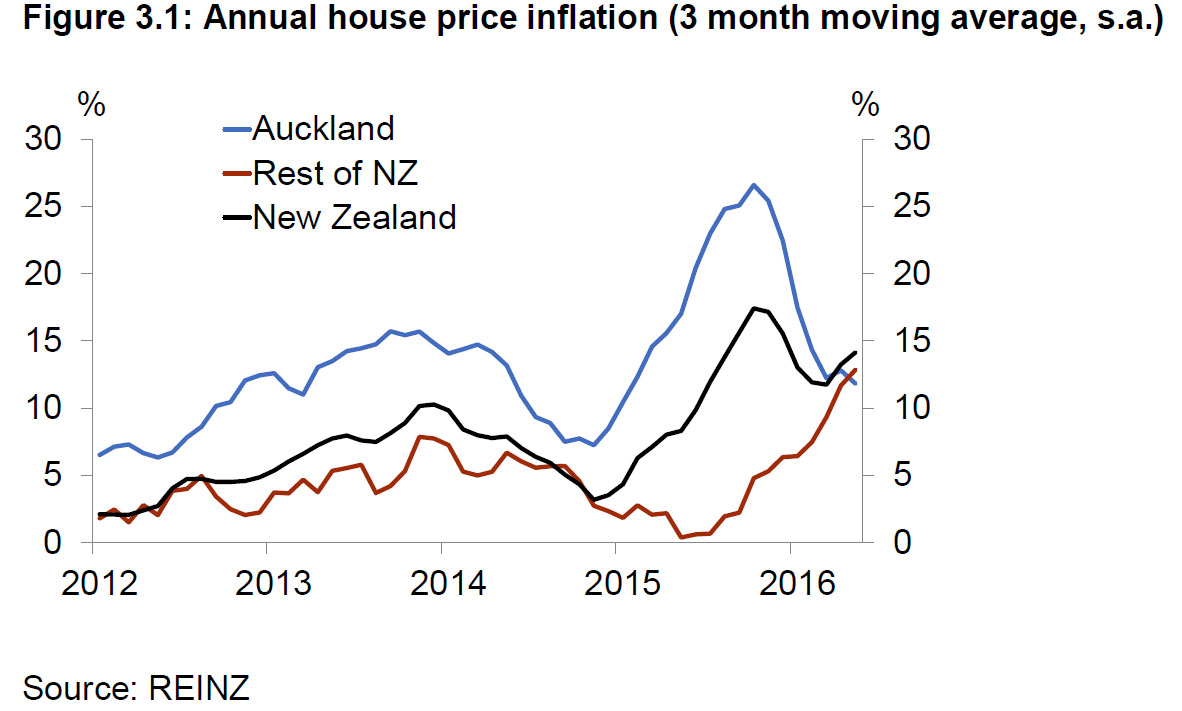

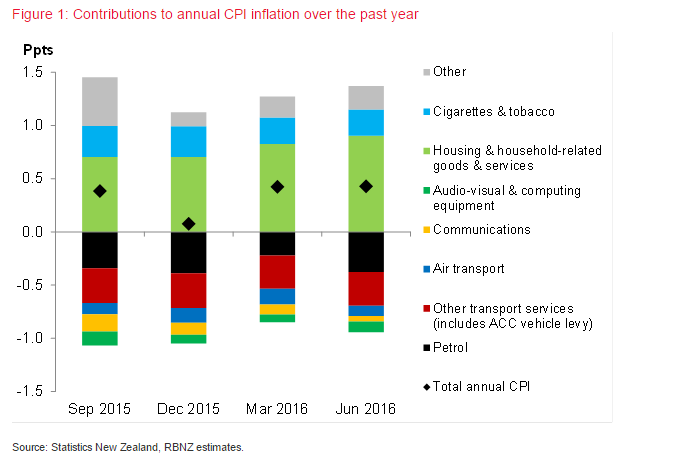

Actual inflation has been low, despite robust growth in the New Zealand economy. Looking at individual items in the CPI basket, low annual inflation in the September quarter is expected to result from: falling prices for petrol; further reductions in ACC vehicle levies (resulting in cheaper car licensing fees); cheaper and better quality audio-visual and computing equipment; and reductions in domestic and international airfares. These lower prices are expected to be only partially offset by increases in the prices of housing-related goods and services – things like construction costs, rents, property maintenance, and local authority rates – and increases in cigarette and tobacco prices. In annual terms, these large negative and positive factors have been at play for at least the past year (figure 1).

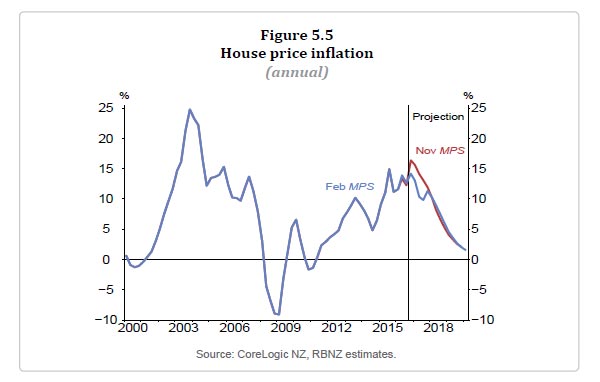

Annual inflation is expected to return to the lower end of the target band in the December 2016 quarter, as previous petrol price declines drop out of the annual calculations and housing-related goods and services prices continue to increase strongly.

Stability in the cost of living maintains the purchasing power of New Zealanders’ incomes. Inflation that is too high or too low has economic costs, and is of concern to the Reserve Bank. High inflation distorts the signals being sent from relative price movements, which results in resources in the economy being misallocated. On the other side, low inflation becomes a concern if it leads to the possibility of deflation. Although we do not see any significant risk of deflation in New Zealand, deflation carries important costs. Deflation would likely lead to consumers and businesses significantly delaying purchases or investment, in the expectation that these will become cheaper in the future. By delaying purchases and investment on a large scale, demand in the economy as a whole is reduced. This then leads to even lower prices. Deflation is particularly concerning as monetary policy eventually reaches a point where it cannot go any lower in order to stimulate the economy (known as the effective lower bound). A buffer above zero inflation is also needed to account for any measurement error in the price index. Across inflation-targeting central banks around the world, inflation of about 2 percent per annum is generally viewed as an appropriate medium-term goal.

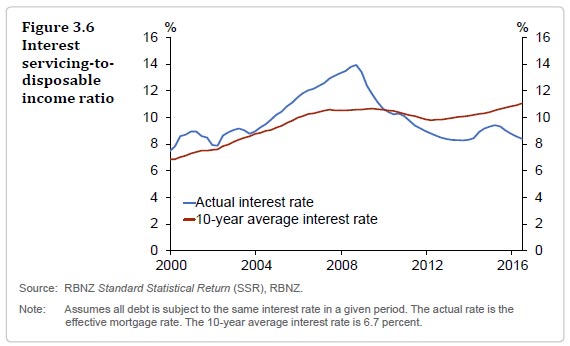

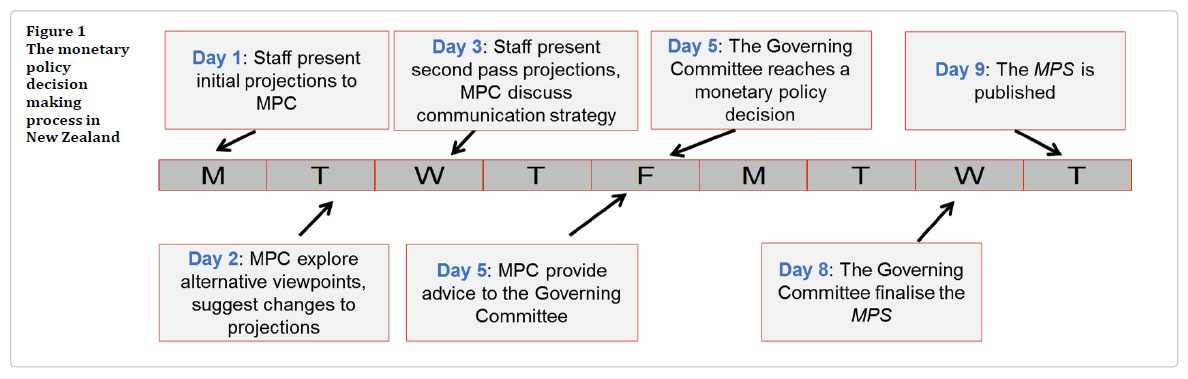

Although headline CPI inflation is expected to remain low in the near term, lowering interest rates now would do little to change these outturns. Monetary policy operates with long and variable lags. Accordingly, monetary policy in New Zealand is focused on the medium-term outlook for inflation, as directed by the Policy Targets Agreement (PTA) between the Governor of the Reserve Bank and the Minister of Finance. Focusing on inflation a year or two ahead avoids unnecessary instability in output, interest rates and the exchange rate, again consistent with the PTA. The Reserve Bank must also have regard to the efficiency and soundness of the financial system.

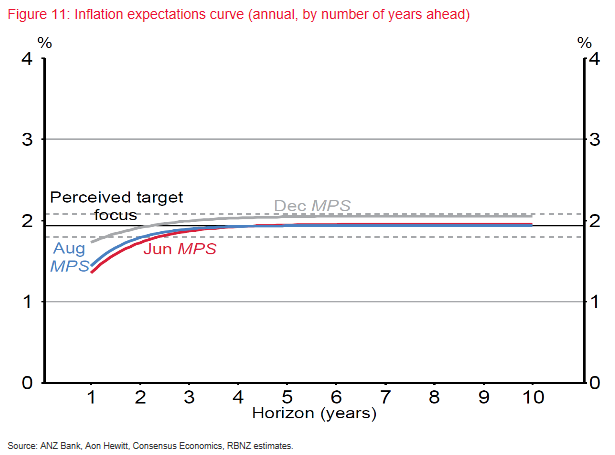

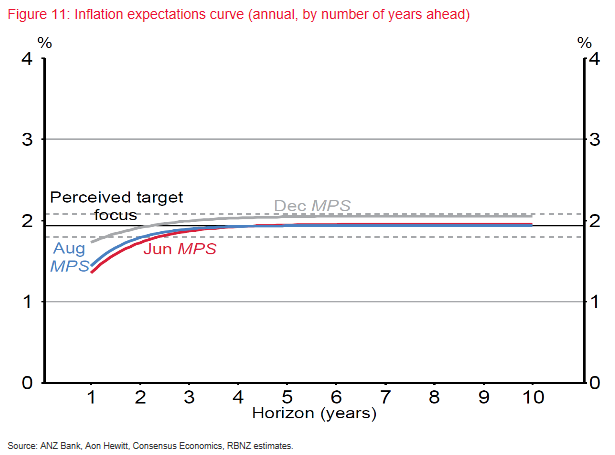

The Bank responds to low inflation outcomes if these outcomes are expected to have an effect on medium-term inflation. If households and businesses respond to low inflation outcomes by reducing their expectations for future inflation, and wages and prices are set accordingly, then these lower inflation expectations would weigh on future actual inflation over the horizon relevant for monetary policy. We carefully monitor developments in inflation expectations, at various horizons.

Looking back over recent years, annual CPI inflation in New Zealand has been lower than expected by the Bank and other forecasters. Understanding why this has been the case – and what the effects on inflation expectations have been – is important in order to set policy going forward.

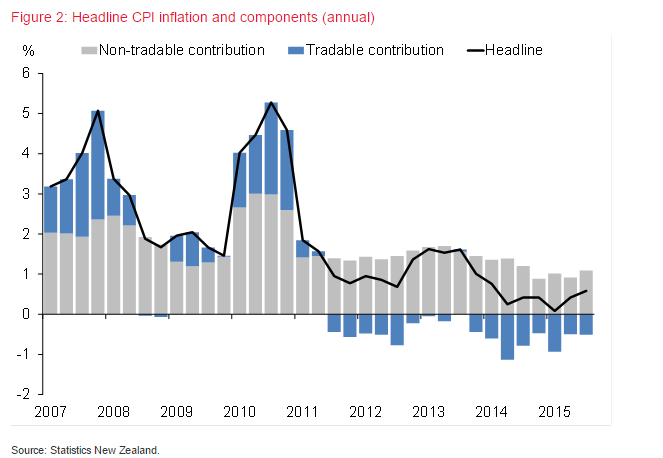

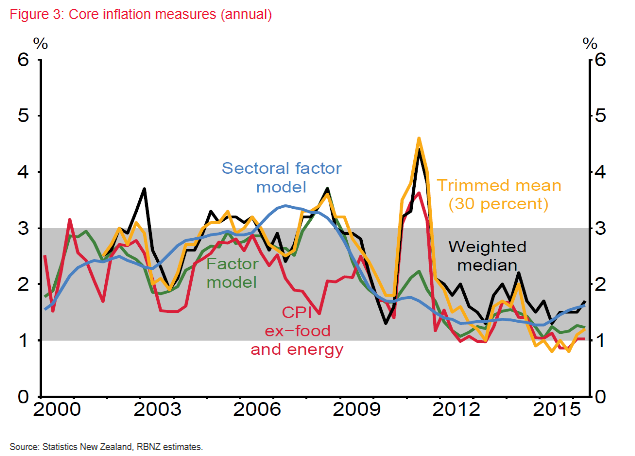

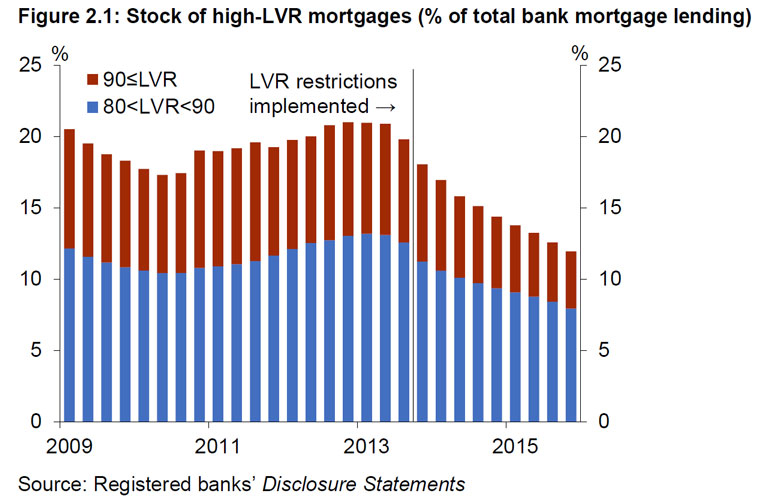

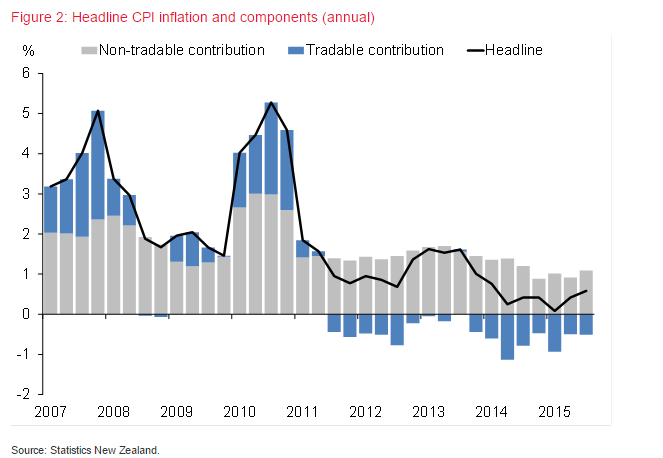

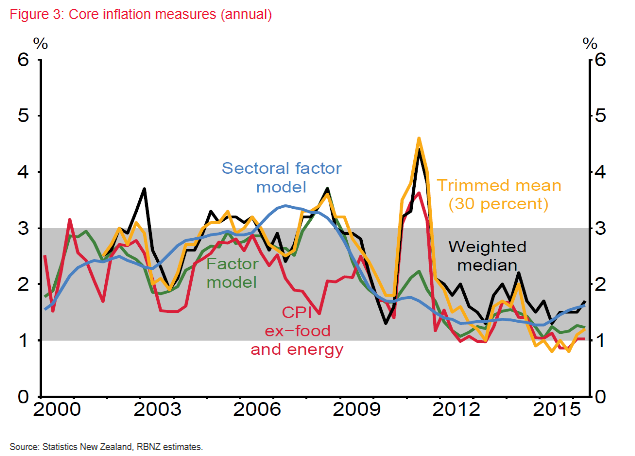

Annual CPI inflation has been below the 2 percent target mid-point since it was formalised in 2012, and below the bottom of the target band since the final quarter of 2014. Low inflation has been accounted for by an unusually long period of falling prices in the tradables sector (those exposed to international competition), as well as a decline in average non-tradables inflation (figure 2). Various measures of core inflation have also been low, although appear to have trended higher since the start of 2015 (figure 3).

At a high level, low inflation could be due to two factors:

- Developments in the cyclical drivers of inflation; or

- Structural changes in the way in which the New Zealand economy generates inflation.

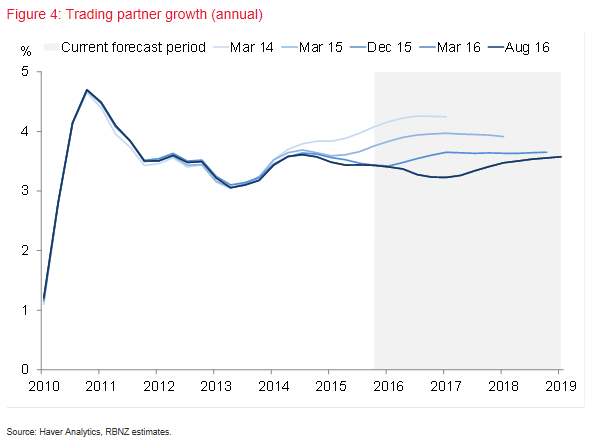

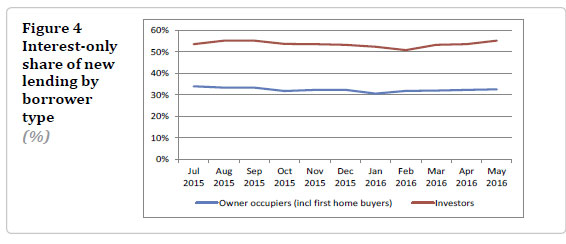

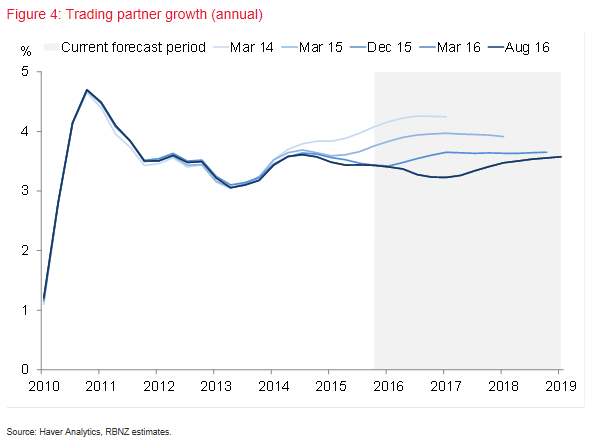

A key factor that has led to low inflation has been the underlying weakness in the global economy (figure 4). Although GDP growth in New Zealand’s trading partners has been near average levels, this moderate growth has required a significant degree of monetary stimulus abroad in the major economies. Quantitative easing and negative interest rates have become regular features of the global economy.

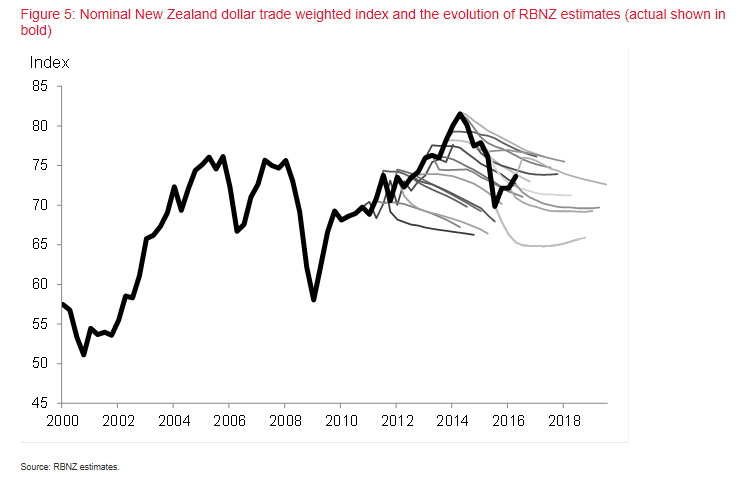

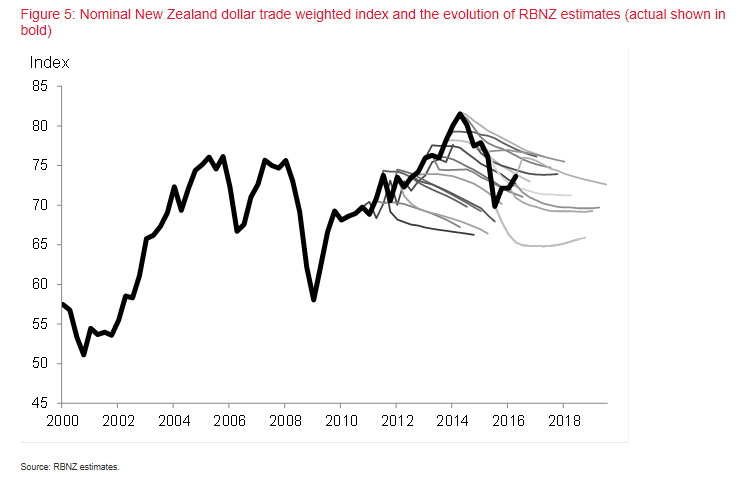

A weak world economy has been a key factor underpinning the New Zealand dollar, with New Zealand’s performance relative to other advanced economies supporting demand for New Zealand dollar assets. The New Zealand dollar exchange rate has been higher than the Bank had assumed for much of the period (figure 5). The New Zealand dollar has remained elevated despite periods of increased risk aversion and steep declines in New Zealand’s export prices. The strength of the New Zealand dollar has dampened the prices of New Zealand’s imports, and contributed significantly to the current low inflation, particularly in the tradables sector.

The prices of the goods and services that New Zealand imports have also been lower than expected – even once the effects of high exchange rate have been taken into account. Again, a weak global economy has been the contributing factor, with significant spare capacity across the globe dampening the world prices for New Zealand’s imports.

In addition to this impulse, there was a sharp decline in the price of oil over 2014 and 2015, reflecting a combination of increased global supply and a moderation in growth in emerging economies. This drop in oil prices has contributed further to low inflation in New Zealand.

It is possible that structural changes may have also contributed to negative tradables inflation in New Zealand. This could include developments such as a change in exchange rate pass-through, or a permanent shift in distributor or retailer margins. However, Bank research suggests that such structural developments do not appear to account for weakness in internationally-driven inflation in New Zealand. That is, although movements in the drivers of low tradables inflation – the exchange rate, oil prices and global prices for our imports – have led to negative tradables inflation, it does not appear that there has been a material or permanent change in the ways that these drivers transmit through to domestic inflation.

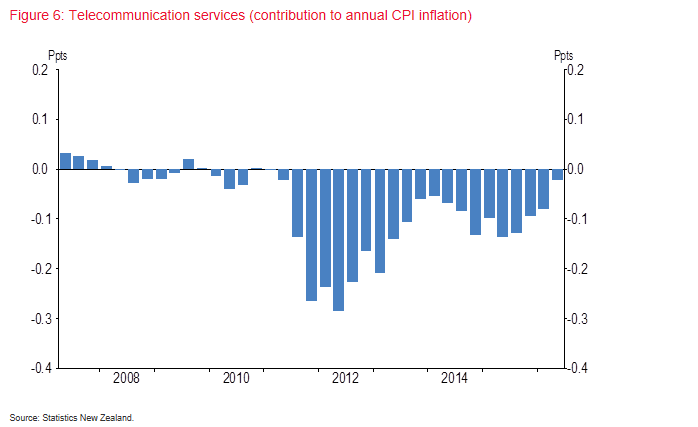

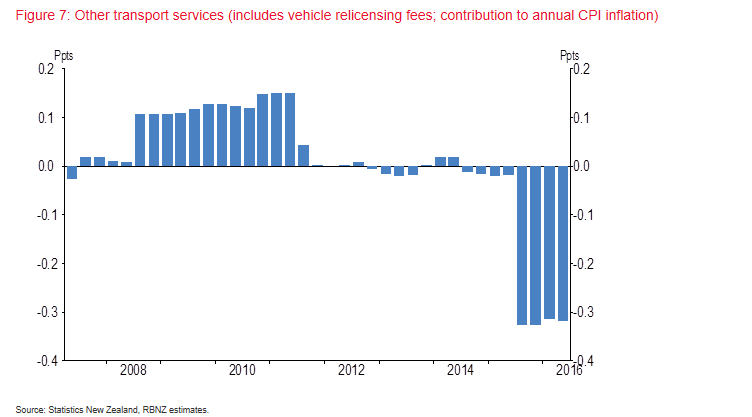

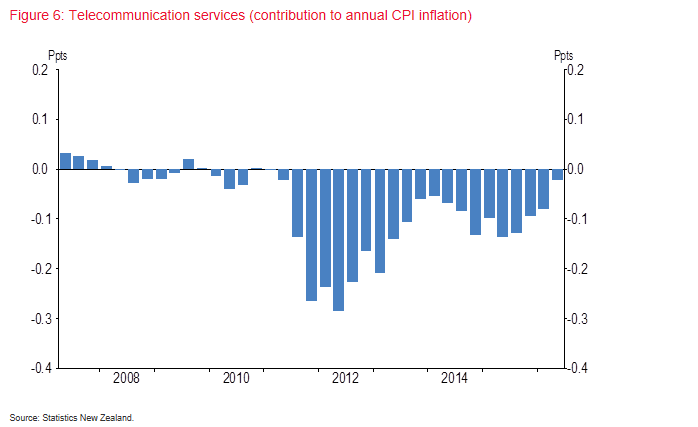

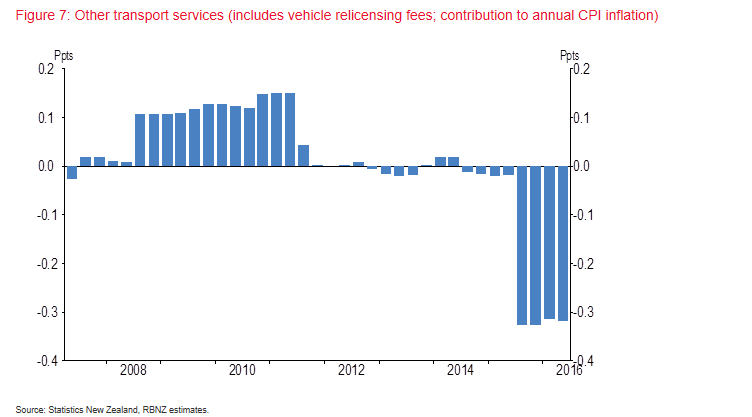

Domestic inflation in recent years has been dampened by some sector-specific factors. Communications prices have been falling since 2011 (figure 6). The lower measured prices reflect an increase in quality: an increase in the size of broadband packages offered (at similar monthly charges); increased data and call minutes for mobile services; and the more-recent introduction of ultra-fast broadband. The net reduction in vehicle relicensing fees (reflecting a change in the way ACC calculates levies for light vehicles) has also held inflation lower since the September 2015 quarter (figure 7).

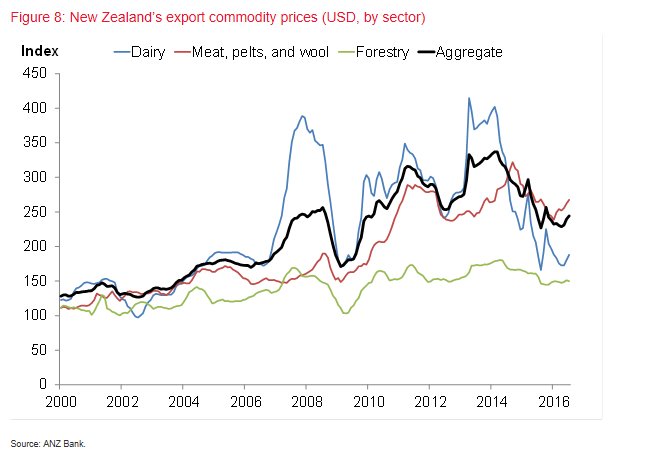

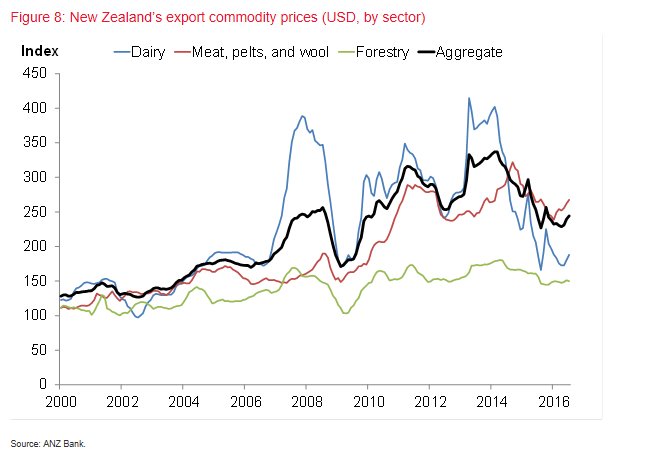

Other cyclical developments have also contributed to weakness in non-tradables inflation. New Zealand experienced a sharp decline in the prices of its exports over 2014, following a boom in commodity prices that had seen New Zealand’s terms of trade reach a 40-year high. The key driver of the fall was a substantial decline in the global price of dairy products (figure 8).

A number of developments contributed to the fall in dairy prices over 2014. A broad range of commodity prices declined over that period in line with the sharp decline in the price of oil, likely reflecting a combination of weaker global demand and the pass-through of lower energy costs. More specifically in the international dairy market, supply increased substantially – particularly in Europe following the relaxation and subsequent removal of production quotas that had been in place for nearly 30 years.

This drop in New Zealand’s commodity prices acted as a headwind to the domestic economy, reducing on-farm investment and rural spending. The flow through to demand in the economy more generally ultimately contributed to weaker domestic inflation.

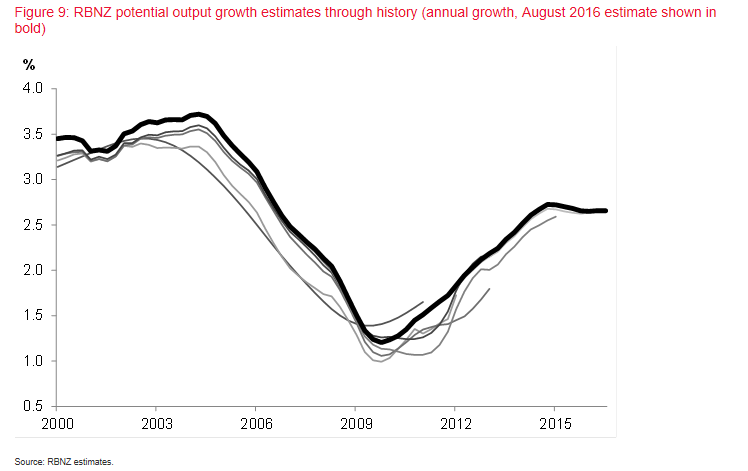

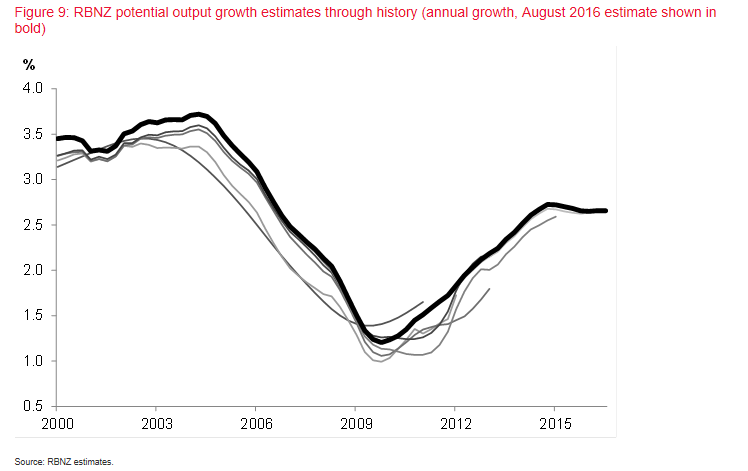

A key structural development that has led to persistent weakness in inflation has been the stronger growth in New Zealand’s potential output (figure 9). This has enabled the New Zealand economy to grow at a robust pace without generating significant inflation, and is likely to continue to do so over the medium term.

Over recent years, most of the increased growth in potential GDP has been due to an increase in labour supply – through greater participation in the labour force and high net immigration. Employers, like yourselves, have been able to absorb this additional labour supply over recent years. More people entering the New Zealand workforce acts to dampen labour costs, and general inflation as a result. The ability of New Zealand businesses to find a productive use for the remarkable increase in the supply of labour is one of the most positive aspects of the current economic expansion.

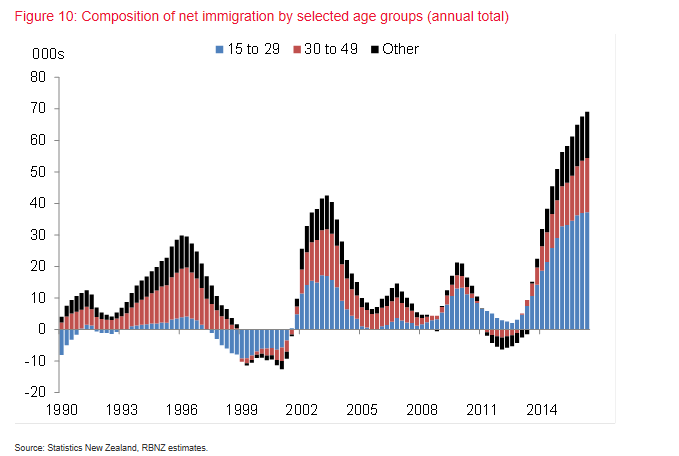

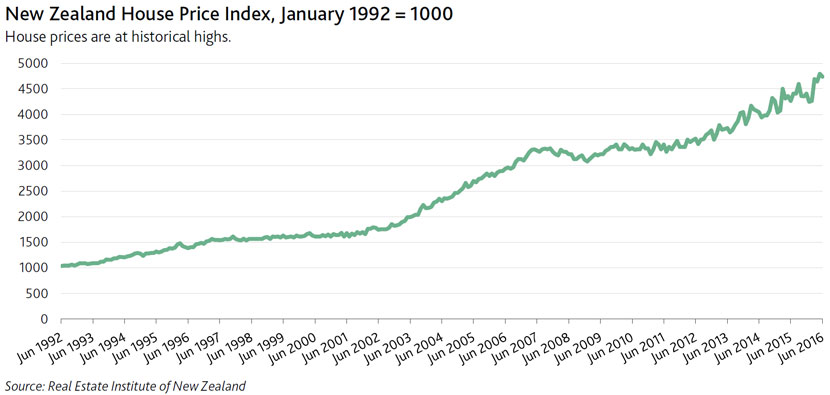

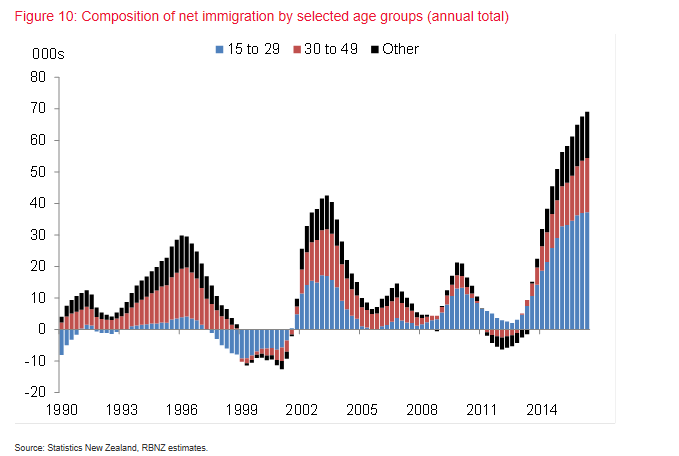

More people increase both demand in the economy and growth in potential output. In previous cycles, the increase in demand has often outweighed the contribution to the supply capacity of the economy. Migration in previous cycles was therefore usually associated with an increase in overall capacity pressures and inflation, as well as a strong pick up in house price inflation.

The consequences of the recent migration inflows on consumer price inflation have been much more modest in this cycle. Two key factors can account for this more muted response. First, the composition of migration matters a great deal for inflationary pressures. Younger migrants (17-29 years old) tend to have a positive but more muted impact on domestic demand compared to older cohorts (30-49 years old). Second, the source of the migration impulse also matters – higher inward migration to New Zealand that is driven by a weaker Australian economy tends to result in a higher unemployment rate – all else equal – while inward migration to New Zealand driven by other factors has the opposite effect. That is, people who move to New Zealand because their job prospects in Australia have deteriorated are likely to spend less once here.

In recent years, we have seen a larger share of younger migrants than in previous cycles (figure 10), and weakness in the Australian labour market has been a driver of trans-Tasman flows.

There also appears to have been a structural change in how households and businesses form their expectations of prices. Inflation expectations now seem to respond more to past inflation outcomes than they did prior to the global financial crisis (GFC). This would mean any direct shocks to headline inflation (even if the shocks themselves are expected to be short-lived) now appear to have more persistent effects on inflationary pressures than they did in the past, via the expectations channel. This suggests that weak tradables inflation may have had a greater dampening impulse on non-tradables inflation through inflation expectations than would have occurred in previous periods.

Two key factors that businesses and households take into account when setting prices are the degree of capacity pressure and inflation expectations. The Bank has reviewed its frameworks for estimating capacity pressure (also known as the ‘output gap’ – the difference between actual and potential GDP) and inflation expectations in New Zealand.

Reserve Bank research re-emphasised the challenge in accurately estimating the output gap in real time. When assessed against a vast range of possible capacity indicators, the Bank’s estimate of the output gap in 2015 was around the middle of this range of estimates.

The Bank also developed a methodology to better incorporate and monitor the vast amount of information on inflation expectations into the Bank’s policy making. The analysis shows that low inflation outcomes have lowered expectations of inflation at shorter horizons, which may dampen near-term price- and wage-setting. However, analysis points to longer-term inflation expectations remaining well anchored close to the mid-point of the bank’s inflation target (figure 11).

In view of low inflation outturns since 2014, the Bank undertook a review of its forecasting performance. Reviews of forecast performance help to update our understanding of economic relationships and identify any areas were we could improve our accuracy. Generally, the Bank’s recent forecasts have performed better than external benchmarks. Looking at the period since the GFC, the Bank has generally been better than others at forecasting inflation, and its forecasts have been of a similar quality to those produced by a suite of statistical models. This forecast review suggests that there were no obvious sources of new information that the Bank could reasonably have been expected to incorporate when preparing its forecasts.

Conclusion

Annual CPI inflation for the September quarter is going to be low, as incorporated into the Bank’s most recent projections. However, it is expected to rise in the December quarter and be at the bottom of the target range as the transitory effects of earlier declines in oil prices dissipate. As described in the September OCR Review, monetary policy will continue to be accommodative. Our current projections and assumptions indicate that further policy easing will be required to ensure that future inflation settles near the middle of the target range.

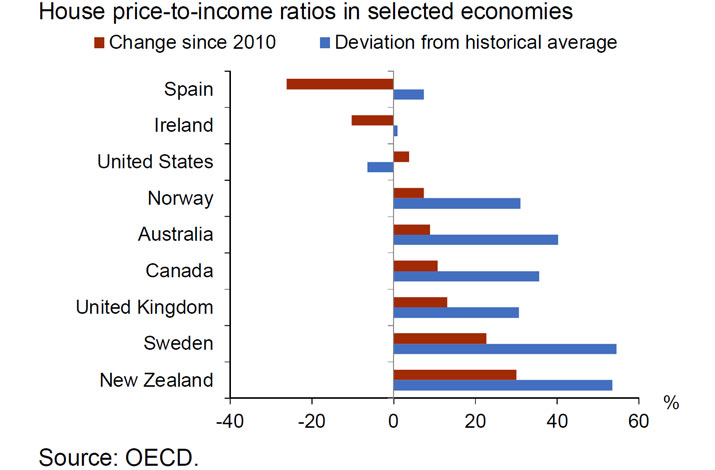

Actual inflation has been low, and lower than forecast, for several years – both here and abroad. The potential reasons for this are a topic of discussion around the world. In New Zealand, much of this weakness can be attributed to global developments that have presented themselves via the high New Zealand dollar and low inflation in our import prices. Strong net immigration and increased labour market participation have also boosted the supply potential of the economy, meaning that New Zealand has been able to grow at a robust pace without generating significant inflation.

There also appear to have been changes in how inflation is generated in New Zealand: the drivers and composition of net immigration influence the degree of associated inflationary pressure for any given migration flow, and inflation expectations appear to now place more weight on past inflation outcomes than they did prior to the GFC. The Bank will continue to closely monitor developments in the drivers of inflation and investigate any persistent changes in how inflation is generated. Our goal will be to achieve future inflation outcomes within the target range on average over the medium term, with a focus on keeping future average inflation near the target mid-point.