And, over the past year, there has been a surge of enthusiasm for developing a sector of large-scale institutional landlords, modelled on the UK’s build-to-rent sector or “multi-family” housing in the US.

Our review of the private rental sectors of ten countries in Australasia, Europe and North America identified innovations in rental housing policies and markets Australia might try to emulate – and avoid. International comparisons also give a different perspective on aspects of Australia’s own rental housing institutions that might otherwise be taken for granted.

Not everyone in Europe rents

In nine of the ten countries we reviewed, private rental is the second-largest tenure after owner-occupation. Only in Germany do more households rent privately than own their housing. Most of the European countries we reviewed have higher rates of home ownership than Australia.

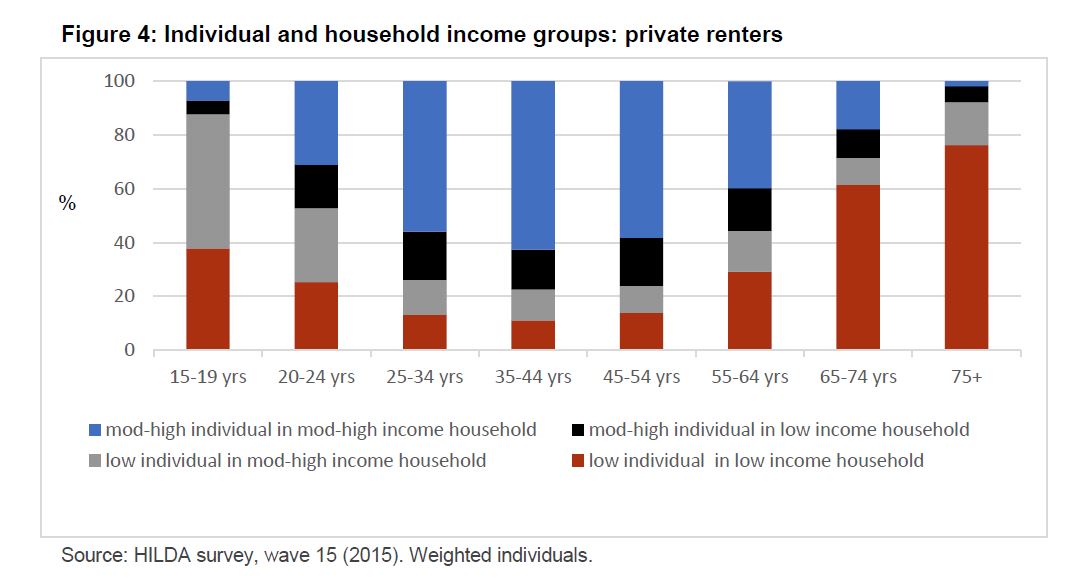

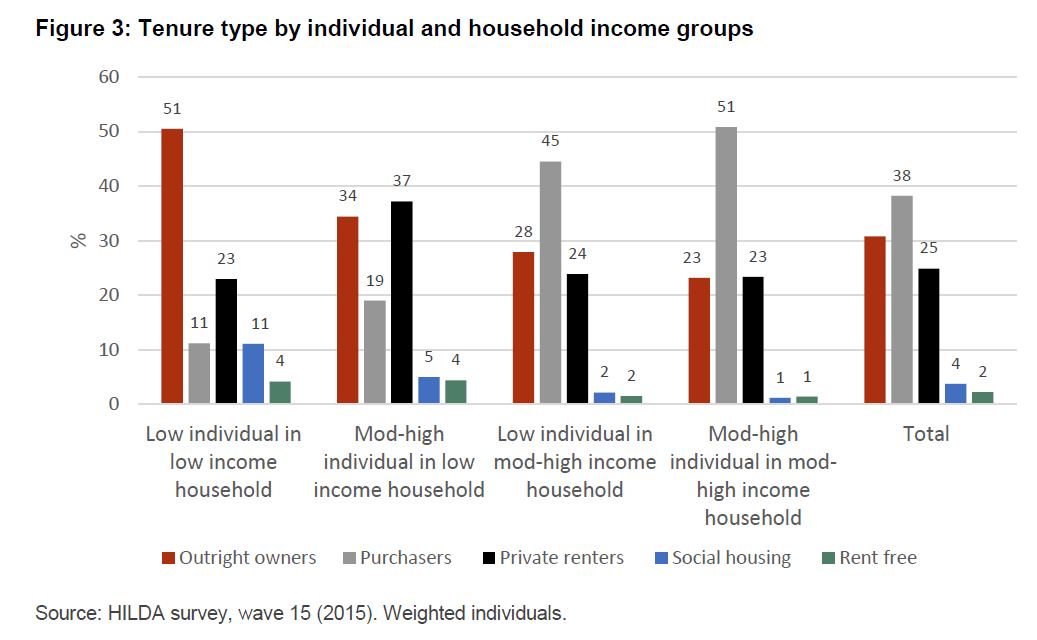

In most of the European and North American countries in our study, single people and lower-income households and apartments are heavily represented in the private rental sector. Higher-income households, families with kids, and detached houses are represented much more in owner-occupation. It’s less uneven in Australia: more houses, kids and higher-income households are in private rental.

Two key potential implications follow from this.

First, it suggests a high degree of integration between the Australian private rental and owner-occupier sectors, and that policy settings and market conditions applying to one will be transmitted readily to the other.

So, policies that give preferential treatment to owner-occupied housing will also induce purchase of housing for rental, and rental housing investor activity will directly affect prices and accessibility in the owner-occupied sector.

It also heightens the prospect of investment in both sectors falling simultaneously, with little established institutional capacity for countercyclical investment that makes necessary increases in ongoing supply.

A second implication relates to equality. Australian households of similar composition and similar incomes differ in their housing tenure – and, considering the traditional value placed on owner-occupation, this may not be by choice.

This suggests housing tenure may figure strongly in the subjective experience of inequality. It raises the question of whether housing is a primary driver of inequality, and not the outcome of difference or inequality in other aspects of life.

The rise of large corporate landlords

In almost all of the countries we reviewed, the ownership of private rental housing is dominated by individuals with relatively small holdings. Only in Sweden are housing companies the dominant type of landlord.

However, most countries also have a sector of large corporate landlords. In some countries, these landlords are very large. For example, America’s five largest corporate landlords own about 420,000 properties in total. Germany’s largest landlord, Vonovia, has more than 330,000 properties alone.

These landlords’ origins vary. Germany’s arose from massive sell-offs of municipal housing and industry-related housing in the early 2000s.

In the US, multi-family (apartment) landlords have been around for decades. And in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, they have been joined by a new sector of single-family (detached house) landlords that have rapidly acquired large portfolios from bulk purchases of foreclosed, formerly owner-occupied homes.

In these countries and elsewhere, the rise of largest corporate landlords has been controversial. Germany’s have a poor record of relations with tenants – to the extent of being the subject of popular protests in the 2000s – and their practice of characterising repairs as improvements to justify rent increases.

American housing advocates have voiced concern about “the rise of the corporate landlord” – especially in the single-family sector, where there’s some evidence that they more readily terminate tenancies.

These landlords also don’t build much housing. They are most active in renovating (for higher rents), merging with one another, and – especially in the US – developing innovative financial instruments such as “rental-backed securities”.

“Institutional landlords” are now a standing item on the Australian housing policy agenda. Considering the activities of large corporate landlords internationally, we should get specific about the sort of institutional landlords we really want, how we will get them, and how we will ensure they deliver desired housing outcomes.

Policymakers and housing advocates have, for years, looked to the community housing sector as the prime candidate for this role. They envisage its transformation into an affordable housing industry that works across the sector toward a wide range of policy outcomes in housing supply, affordability, security, social housing renewal and community development.

With interest in the prospect of build-to-rent and multifamily housing rising in the property development and finance sectors, there is a risk that affordable housing policy may be colonised by for-profit interests.

The development of a for-profit large corporate landlord sector may be desirable for greater professionalisation and efficiencies in the management of tenancies and properties. However, this should not come at the expense of a mission-oriented affordable housing industry that makes a distinctive contribution to housing outcomes.

Bringing it home

Looking at the policy settings in the ten countries, we found some surprising results and strange bedfellows.

For example, Germany – which has had a remarkably long period of stable house prices – has negative gearing provisions and tax exemptions for capital gains, much like Australia. But, in Australia, these policies are blamed for driving speculation and booming prices.

And while the UK taxes landlords more heavily than most other countries, it has the fastest-growing private rental sector of the countries we reviewed.

However, these challenging findings should not be taken to diminish the explanatory power or effectiveness of these settings in each country’s housing policy. Rather, they show the necessity of considering taxation and other policy settings in interaction with each other and in wider systemic contexts.

So, for example, Germany’s conservative housing finance practices, and regulation of rents, may mean the speculative potential of negative gearing and tax-free capital gains isn’t activated there.

Strategy in Australia for its private rental sector should join consideration of finance, taxation, supply and demand-side subsidies and regulation with the objective of making private rental housing outcomes competitive with other sectors.