The insecurity of rental housing and unsatisfactory condition of many properties are receiving much-deserved media attention following the release of a national survey of tenants.

However, the stock response to the insecurity this revealed – longer fixed-term agreements – is not the answer. The solution to the failure of existing legal protections must take into account the structural features of the rental market, including the mobility of tenants.

The survey, commissioned by Choice, National Shelter and the National Association of Tenant Organisations, presents evidence of a widespread sense of worry, dissatisfaction and injustice on the part of tenants. According to respondents:

- 75% feel that competition for rental properties is “fierce”;

- 50% are concerned about being “blacklisted” on a tenancy database;

- 50% have experienced some form of discrimination;

- 30% live in properties requiring non-urgent repairs, and 8% require urgent repairs;

- 11% experienced a rent increase; and

- 10% reported an angry response after requesting repairs.

Residential tenancy laws cover many of these problems. That tenants are not successfully exercising their legal rights indicates a deeper problem of insecurity in renting. This problem is both structural and legal.

Small landlords and mobile tenants

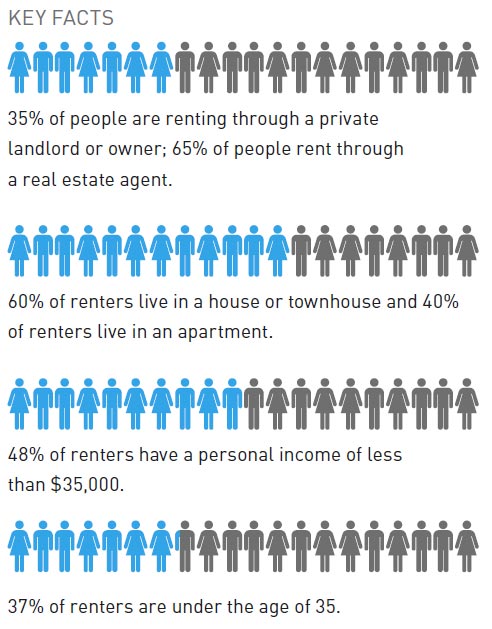

Small landlords dominate the Australian rental sector: 72% own a single property each. Most (62%) make a net rental loss, so it is important to them that they can switch out of the sector when it suits them.

Research for the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) indicates that 21% of landlords exit the sector within their first 12 months. By five years, 59% will have exited.

When landlords exit, they might sell to another landlord or an owner-occupier. Older research indicates that the transfer of rental housing into owner-occupation is a significant feature of the Australian market.

These dynamics cause structural insecurity for tenants. They also mean many landlords do not willingly tie up their sole asset in a long fixed term.

Despite the legal and structural insecurity of the sector, most moves by tenants are for their own reasons.

The ABS Housing Mobility and Conditions survey shows that tenants generally are very mobile: 81% have been in their current premises for less than five years. About half of moves between rental premises were for “personal reasons” (including family and employment reasons); 20% were to get more suitably sized housing; and 15% because of a termination notice from the landlord.

This degree of mobility suggests it is not in most tenants’ interest to enter into long fixed terms and the rental liability it entails. That’s not to mention the risk of being tied to a small landlord who is an unknown quantity and has no business reputation to protect.

Residential tenancies law in Australia

Each state and territory in Australia has its own Residential Tenancies Act. These differ in the details but are broadly similar in outline. All provide standard terms for tenancy agreements, processes for rent increases and terminations, and relatively accessible dispute resolution and eviction procedures.

Most do a decent job, on paper at least, when it comes to repairs and maintenance. Generally speaking, landlords are obliged to ensure rented premises are provided fit for habitation and maintained in a reasonable state of repair.

This means tenants are entitled to repairs even if the premises were in bad condition to begin with, and even if they pay relatively low rent. Tasmania is an exception: there, landlords are obliged to maintain premises in the condition in which they were first provided.

Similarly, each state and territory prohibits landlords from interfering in tenants’ quiet enjoyment of their premises. Most expand this right to protect tenants’ “reasonable peace, comfort and privacy”.

These are important protections, even though there may be scope to improve them – for example, by adding specific standards for safety devices and fixing particular legal defects like Tasmania’s. The great problem is that the ability of landlords to give notices of termination without grounds undermines the existing protections in every state and territory.

Without-grounds termination notices give cover to terminations by landlords for bad reasons, such as retaliation and discrimination. This means the prospect of receiving such a notice hangs over tenants when repairs and other issues arise.

What’s the solution, then, to high insecurity?

The legal insecurity of tenants might be improved in several ways.

Under the current laws of each state and territory, a fixed term prevents the landlord from terminating without grounds, and on other grounds such as sale or change of use of the premises, for the duration of the fixed term. It also prevents the tenant from lawfully terminating without grounds.

The idea of long fixed-term tenancy agreements is occasionally raised in the media and has caught the attention of the New South Wales and Victorian governments in their reviews of residential tenancies laws. Both those governments are considering how to facilitate long (five-year) fixed terms, including by altering other aspects of their laws – such as the protections about repairs.

But this approach presents problems of its own. Long fixed terms are unwieldy for landlords and tenants. Trying to make them more useful also threatens other valuable legal protections.

The present structures of the Australian rental sector call for different reforms.

We can reconcile the mobility of tenants with their sense of insecurity if we think of “security” as more than just the legal right to occupy. AHURI researchers have conceived of “secure occupancy” to encompass a person’s ability to make a home of premises and exercise housing autonomy. This includes the ability to confidently get repairs done in one’s premises, or keep a pet – and to freely decide to make a new home elsewhere.

This conception points towards a stronger reform agenda for improving security. Instead of long fixed terms, we should abolish without-grounds termination by landlords.

The law should instead provide a comprehensive set of reasonable grounds for termination, with notice periods and exclusion periods appropriate to each ground. This accommodates our present lot of small landlords, and can be done immediately.

Over a longer term, we should set our housing tax and finance policies to get a more stable sort of landlord. That would be one who operates at greater scale, has a reputation to protect and is less interested in switching out of the sector than in receiving a steady trickle of rents from secure tenants.