Interesting speech from New Zealand, illustrating the difficulty in the current low growth, low rate, low inflation, high exchange rate environment. Expect more rate cuts!

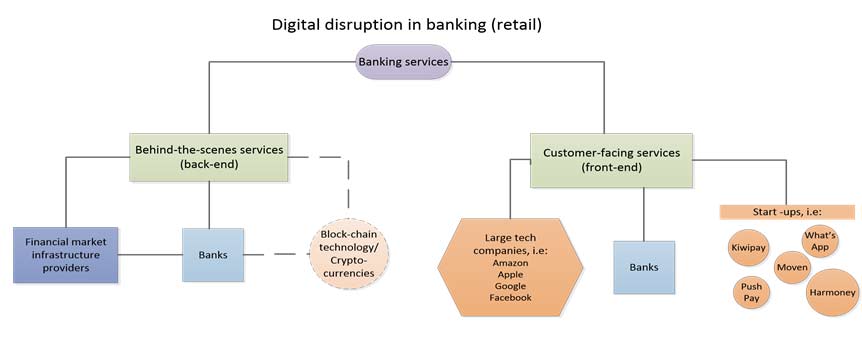

In a speech written for the Otago Chamber of Commerce, Mr Wheeler said the scope and influence of monetary policy, particularly in small, open economies, is heavily constrained by economic and financial developments outside their borders. As a result, expectations of what monetary policy can achieve often run ahead of reality.

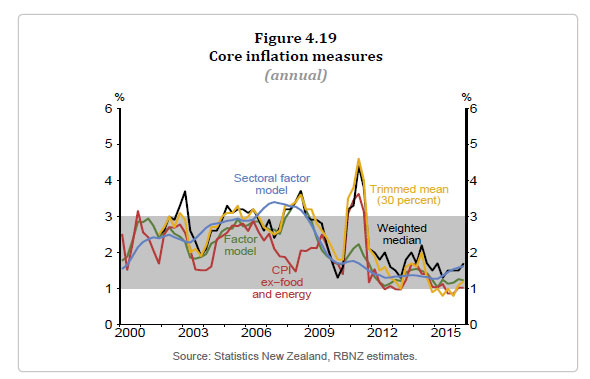

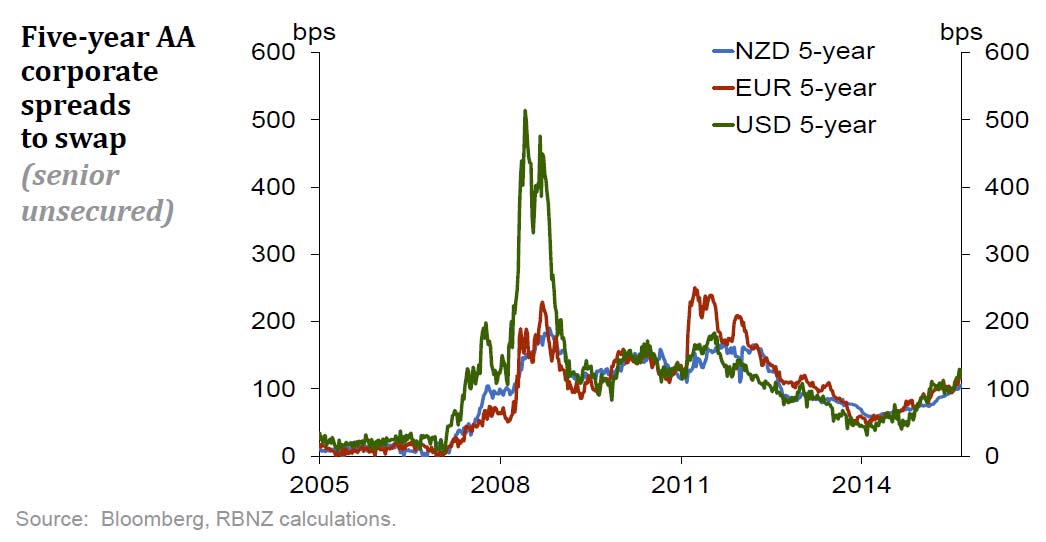

“Nearly 10 years on from the Global Financial Crisis, economies face a difficult global economic and financial climate, with below-trend growth despite unprecedented monetary stimulus, declining merchandise trade and rising protectionism, very low inflation and interest rates, and high asset prices presenting financial stability risks. Many of these issues have complex structural elements that are unlikely to fully self-correct as global growth recovers.

“Central banks must make finely balanced judgements when setting monetary policy, based on evidence, research, scenario analysis, and continual review of their policy record and international experience,” he said.

“As is the case elsewhere, there are a range of views about what monetary policy can achieve and how it should be operated. In New Zealand, these include a view that flexible inflation targeting is no longer an appropriate framework for conducting monetary policy.”

Mr Wheeler said that flexible inflation targeting remains the most appropriate framework for conducting monetary policy in New Zealand. Provided sufficient flexibility is allowed to accommodate the frequent and often severe impact of external shocks, the most important contribution monetary policy can make to promoting efficiency and the long-run growth of incomes, output and employment is the pursuit of price stability.

“There is nothing sacrosanct about what particular inflation band or target should be adopted as a measure of price stability. However, changing a target when times become tougher reduces the incentives on central banks to achieve earlier agreed goals. It could damage the central bank’s credibility – particularly if a perception develops that the central bank will continually seek to respecify goals.”

The Bank also encounters a view that it should not lower interest rates, because current strong economic growth makes interest rate cuts unwarranted and undesirable.

However, if financial markets believe that the Bank is content with below-target inflation, they would conclude that the easing process is over and proceed to bid the exchange rate up, perhaps substantially.

“The TWI exchange rate is already at a high level based on the Bank’s models. A sizeable appreciation would further squeeze incomes in the tradables sector, and drive tradables inflation lower for longer, thereby lowering overall headline inflation.”

Low headline inflation could also bring down inflation expectations in a self-perpetuating spiral.

“If inflation expectations fall too far, it can be very difficult to raise them back up. In such a situation, even further cuts in interest rates would be needed to stimulate economic activity and increase inflationary pressures.”

Mr Wheeler said a third view maintains that the Bank should rapidly lower interest rates to bring inflation quickly back to the mid-point of the inflation band.

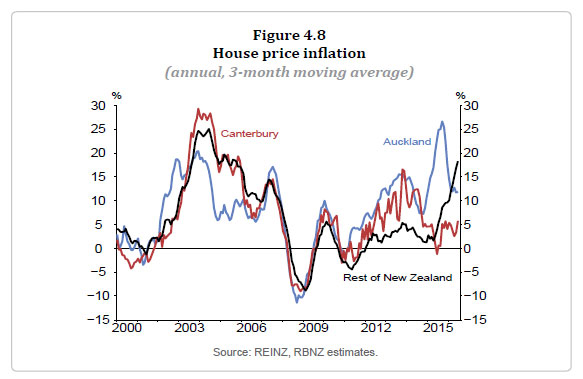

However, an aggressive monetary policy that is seen as exacerbating imbalances in the economy would not be regarded as sustainable, and would not deliver the exchange rate relief being sought.

Rapid ongoing decreases in interest rates would likely result in an unsustainable surge in growth, capacity bottlenecks, and further inflame an already seriously overheating property market. It would use up much of the Bank’s capacity to respond to the likely boom/bust situation that would follow, and place the Reserve Bank in a situation similar to many other central banks of having limited room to respond to future economic or financial shocks.

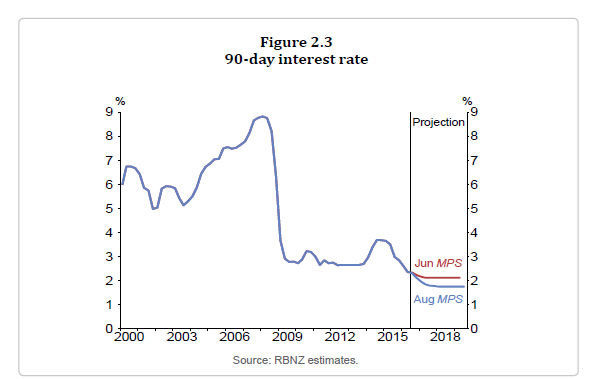

Mr Wheeler drew heavily on and emphasised the messaging contained in the recently released August Monetary Policy Statement.

“The key rationale for cutting the OCR in August was to lower the risk of a further decline in short-term inflation expectations.

“Our present judgement is that the current interest rate track, involving an expected 35 basis points of further interest rate cuts, balances a number of risks weighing on the economy, while generating an increase in CPI inflation back towards the mid-point of the 1 to 3 percent target range.

“We remain committed to the inflation goals in the Policy Targets Agreement. We do not believe that the outlook and balance of risks warrants a position of no policy change, nor a position of rapid easings. If the emerging information and risks unfold in a manner that warrants a change in our judgements, we will modify our policy settings and outlook.”