Philip Gaetjens, Secretary to the Treasury addressed the Senate Estimates today on the budget. We are being helped by super-high iron ore prices, but downside risk sits in the household sector, and especially, the falls in property and household consumption.

Fiscal outlook

The Budget forecasts an underlying cash surplus in the 2019-20 financial year of $7.1 billion, the first surplus since 2007-08. It is then forecast to increase to a surplus of $11 billion in 2020-21, with sustained surpluses projected into the medium term. The fiscal outlook continues to benefit in particular from commodity prices that have remained at elevated levels, coupled with continued growth in resource exports, which both support further expected improvement in company tax collections in 2018‑19 and 2019-20.

Ongoing strength in iron ore and metallurgical coal prices since the MYEFO and a consequent delay in the assumed phase down in these prices have contributed to a higher terms of trade in 2018‑19. The Budget prudently assumes a return to more sustainable levels over the next four quarters. Nominal GDP growth is expected to be 3¼ per cent in 2019-20, ¼ of a percentage point lower than at the MYEFO, and 3¾ per cent in 2020-21. In contrast to the upgrade in the terms of trade, growth in real GDP and domestic prices have been revised down, reflecting data since MYEFO, including the weaker‑than‑expected December quarter 2018 National Accounts released on 6 March.

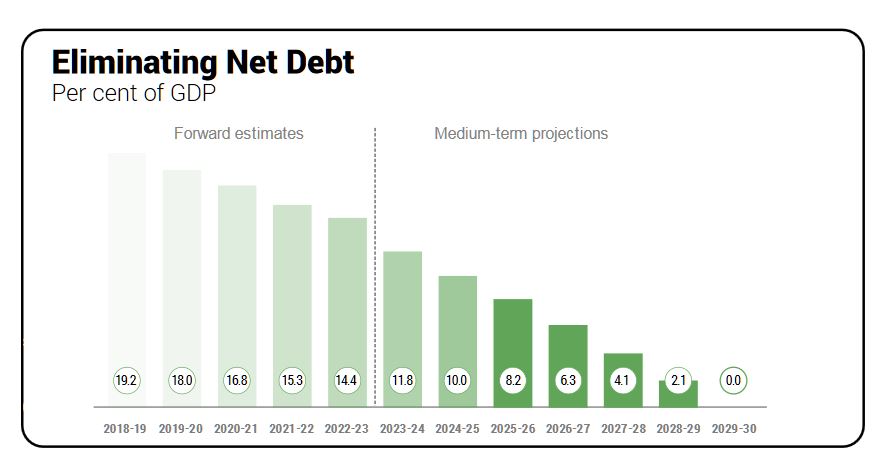

As I noted in my last statement to the committee, the path to returning the budget to surplus has been a long one and reflects the long lasting fiscal impacts of financial shocks and economic transitions that occur as an economy rebalances. The long run of deficits has also left Australia with substantially higher public debt levels. The improved fiscal outlook now enables a greater focus on public debt reduction to improve Australia’s position to meet future domestic and international challenges.

In the Budget, gross debt is expected to be 27.9 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, falling to 25 per cent of GDP at the end of the forward estimates and further to 12.8 per cent of GDP by the end of the medium term. Net debt is also expected to decline in each year of the forward estimates and the medium term, falling from 18 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 to a projected zero per cent by 2029-30.

Domestic economic outlook

The economic data released since MYEFO were a bit weaker than had been expected, which I highlighted in my address to the committee in February. The December quarter 2018 National Accounts data confirmed the slowing in momentum in the real economy in the second half of 2018, although this followed two quarters of strong growth earlier in the year.

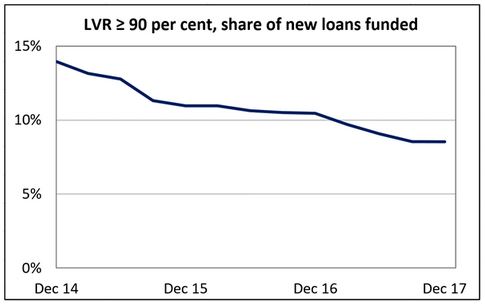

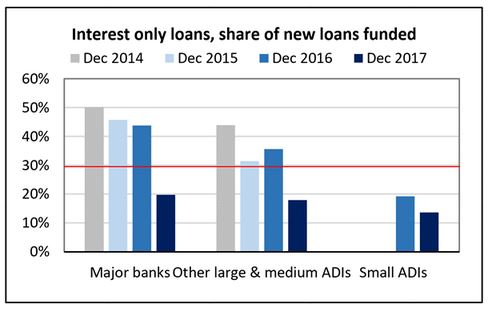

Spending by the household sector, on both consumption goods and housing, has moderated. We also know that housing prices have been declining over the past year and a half. Falls in residential building approvals since late 2017 are expected to flow through to lower dwelling investment over the coming years. Consumption of discretionary items has been particularly soft, including for those components that relate to housing market conditions, such as household furnishings and motor vehicles. While the pick‑up in growth in retail sales in February was welcome, it followed a number of weak outcomes.

In contrast, non-mining investment has continued to grow at a solid pace and spending by the public sector, including on services, such as health and education, as well as on infrastructure, has been growing above its long-run average rate. Mining investment is expected to grow in 2019-20 for the first time in around seven years.

Despite some weakness in the real economy, there has been continued strength in the labour market. Employment growth was above its long-run average over the year to February, and the unemployment rate is now 4.9 per cent, a rate last recorded in June 2011. The participation rate is close to its record high.

Growth in real GDP is forecast to be 2¾ per cent in 2019-20 and 2020-21. This is around Australia’s estimated potential growth rate. Growth overall is expected to be supported by accommodative monetary policy settings and the Australian dollar, which is one-third lower than its 2011 peak against the US dollar.

Household consumption, business investment, and public final demand are expected to contribute to growth over the forecast period. Dwelling investment is expected to detract from growth over the forecast period, particularly in 2019-20.

Solid economic growth is expected to continue to support employment growth, which is forecast to be 1¾ per cent through the year to the June quarter 2020 and the June quarter 2021. Consistent with positive employment prospects, the participation rate is forecast to be 65½ per cent and the unemployment rate is expected to be 5 per cent across the forecast period. As economic growth strengthens and spare capacity in the labour market continues to be absorbed, wage growth is expected to pick up.

Before moving onto the global economic outlook, I would like to take a moment to emphasise the importance of business liaison in formulating Treasury’s economic forecasts. In the lead-up to the Budget, Treasury conducted business liaison with a range of stakeholders, including banks, mining companies, industry bodies, economists, state and territory governments, representative organisations and small businesses. These consultations provide detailed forward-looking insights on the economic outlook, which directly inform our deliberations on the economic forecasts. Our business liaison activity also substantially benefits from Treasury’s state office presence in Sydney, Melbourne and Perth.

Global economic outlook

Moving now to the global economic outlook, since MYEFO there has been some deterioration in the outlook for global growth, particularly in the euro area and economies outside of Australia’s major trading partners. Reflecting this, forecasts for global growth have been downgraded. Nonetheless, growth in Australia’s major trading partners is forecast to continue to be robust, at 4 per cent in each of the forecast years. Labour market conditions continue to be strong and inflation remains relatively contained in most major advanced economies compared with historical experience.

The United States economy continues to grow solidly. Wage growth has picked up and inflation has increased slightly, closer to the target rate. Growth in China is moderating, reflecting weaker domestic demand as authorities address risks in the financial system and trade pressures weighing on business confidence. With help from targeted macroeconomic policies, China is expected to achieve the authorities’ target of 6.0 to 6.5 per cent growth this year. ASEAN-5 economies continue to perform solidly, with domestic demand and favourable demographics supporting growth.

As outlined in the Budget, there is a high degree of global uncertainty, which appears to be weighing on measures of global confidence amid a range of economic and geopolitical risks. These risks include continued concerns about trade protectionist sentiment, high levels of debt in a range of countries, including in Europe, and Brexit risks, although Australia’s trade is oriented more towards Asia than Europe. In the near term, there is also uncertainty about how quickly activity in some countries will bounce back from temporary factors that weighed on growth in the second half of 2018.