As reported in The Conversation: Age pensioners have always gone on cruises. But since the budget, we have seen stories emerge of age pensioners changing their behaviour in response to the proposed rebalancing of the age pension asset tests.

Sydney housewife Noelene has bought a holiday cruise to Alaska. Seemingly contradicting sensible living strategies for many older people, financial advisers are now proposing part-pensioners upsize and buy a more expensive house.

It’s surprising behaviour, especially in light of new research from CePAR using government data that demonstrates many age pensioners actually live very frugally. Many pensioners live below even the “modest” retirement standard proposed by ASFA ($23,469 for a single and $33,766 for a couple, who own their own home). Indeed, many pensioners are cautious and keep a cushion of assets, whether because of concern about risk, to pay for age care when frail, or to leave a bequest to children or grandchildren.

What’s changed

Why would age pensioners choose to spend big now? Well, it’s a rational response by part-pensioners to the proposed budget asset tests. If the anecdotal behaviour is writ large, a lot of the potential revenue gains (estimated at A$2.4 billion over 5 years) from the asset test changes may disappear.

Apart from the home, the financial and other assets of age pensioners are tested above a limit, so as to target the pension. The age pension is also subject to an income test. At the moment pensioners are assessed under both the income test and the asset test: whichever test gives the lower pension rate is applied. This allows considerable scope for sophisticated pension planning.

The 2015 budget includes changes to the age pension asset tests which deliver benefits at the low end but which are quite draconian for those who have accumulated some assets.

For homeowners, the asset free areas are to rise from $202,000 to $250,000 for single home owners and from $286,500 to $375,000 for couple home owners, but the asset test taper rate will double, from $1.50 per fortnight ($38 a year) per $1,000 to $3 per fortnight ($78 per year) per $1,000.

Pensioners who do not own their own home – and who are much less well off than those who own a home – will benefit from an increase in their threshold to $200,000 more than homeowner pensioners.

On a superficial view, these seem like reasonable changes. But they may have significant behavioural effects and there could be a better way to achieve the government’s policy goals.

Savings taxed: how the government is changing behaviour

The age pension can be thought of as a universal payment combined with an in-built income tax (the income test, which has a 50% tax rate up to the cut out point) and an in-built wealth tax (the asset test).

The effect of the change in policy is to reduce the asset cut-out point where the age pension ceases. Under current asset taper rules, the effective wealth tax rate in the asset test is 3.9% above the threshold. The budget proposal of a taper of $3 per fortnight per $1,000 implies a wealth tax rate of 7.8% ($78 per year per $1,000) above the new thresholds. With real returns of around 5% on many investments currently, the wealth tax effectively confiscates the whole of the real return above the thresholds.

A home-owner couple will see their pension cease at assets of $823,000 compared to over $1.1 million currently. But this home-owner couple with $823,000 in savings would not necessarily have a higher living standard than a home-owner couple with $375,000 in savings; indeed, it could well be lower.

Overall, under the proposed new system, income from savings would be very heavily taxed. Assuming a return to savings of 5%, the effective marginal tax rate could be as much as 160% (the wealth tax rate of 7.8% divided by a 5% return). This creates a disincentive to save. For the conservative investor the situation is even worse, as products like term deposits offer rates only slightly higher than inflation.

An alternative approach: deeming an income return

The Henry Tax Review and the Shepherd National Committee of Audit both recommended that the separate age pension asset test should be replaced by a comprehensive means test that deems income from assets.

A deeming approach disregards actual income from an asset. Only deemed income is included, based on a sensible choice of rate of return, such as the return on bank interest. At 1.75% and 3.25% rates, this is quite a conservative rate of return.

In fact, we already deem income returns in the current pension system, for assets including bank accounts, term deposits, shares, managed funds, loans to family members and superannuation funds (if you are age pension age).

Widening the deeming rules would return us to the “merged means test” which operated in Australia up to the 1970s. Under the test, all assets apart from the home were deemed to yield 10% per annum and actual income from assets was disregarded. The assumed yield on an annuity purchased at age 65 was 10%. Currently an indexed annuity at that age would yield around a third of that in real terms, and even a “growth” investment strategy will yield only 5% to 6%, so a deeming rate around 6% could be justified.

Deeming rates can be set to achieve the sort of budget savings sought by the government with fewer issues for fairness and perverse incentives. A deeming rate of, say, 6% combines with a pension taper of 50% to give an effective marginal wealth tax rate of 3%. This is much less than the effective 7.8% wealth tax rate in the budget measure.

Deeming allows a pensioner to have either modest income or modest assets but not both. It does not unfairly advantage those who maximise their entitlements by planning under both income and asset tests, as the current system allows. A wider deemed base could save as much at a lower effective wealth tax rate than that proposed by the government.

The bigger picture

Australia has highly generous tax concessions for retirement saving, but quite harsh treatment on the pension side. Why incentivise savings through super tax breaks and then penalise savers under the means test?

Home owner retirees are much better off than those who do not own their home and the age pension means test does not touch the top cohort of superannuation savers who receive a hugely disproportionate share of superannuation tax breaks. In contrast to most middle income savers who eventually need some level of age pension with its implicit wealth tax, the top cohort who don’t need the age pension are never subject to any wealth or bequests tax.

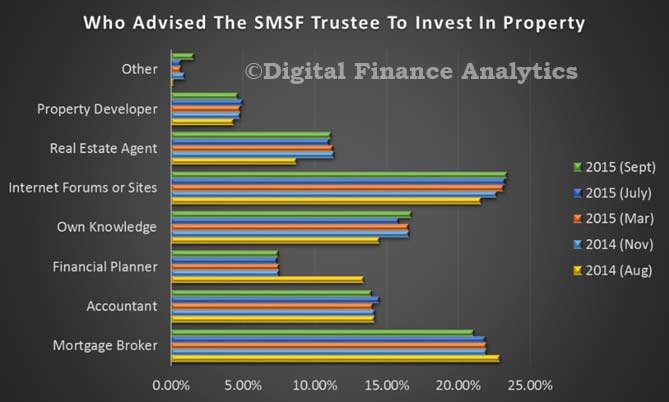

We explored where SMSF Trustees sourced advice to invest in property, 21% used a mortgage broker, 23% online information, 11% a Real Estate Agent, 14% Accountant, and 7% a Financial Planner. Financial Planners are significantly out of favour in the light of recent bank disclosures and ASIC publicity on poor advice.

We explored where SMSF Trustees sourced advice to invest in property, 21% used a mortgage broker, 23% online information, 11% a Real Estate Agent, 14% Accountant, and 7% a Financial Planner. Financial Planners are significantly out of favour in the light of recent bank disclosures and ASIC publicity on poor advice. The proportion of SMSF in property was on average 34%.

The proportion of SMSF in property was on average 34%.