On 20 August, according to Moody’s, Bank Australia Limited sold AUD125 million of three-year sustainability bonds, its first issuance of environment, social and governance (ESG) themed bonds. The bank plans to use the proceeds to finance, or refinance, green and social projects. Bank Australia’s ability to tap the growing demand for ESG investments is credit positive because it adds diversity to its funding sources and allows it to lengthen the overall maturity of its funding portfolio.

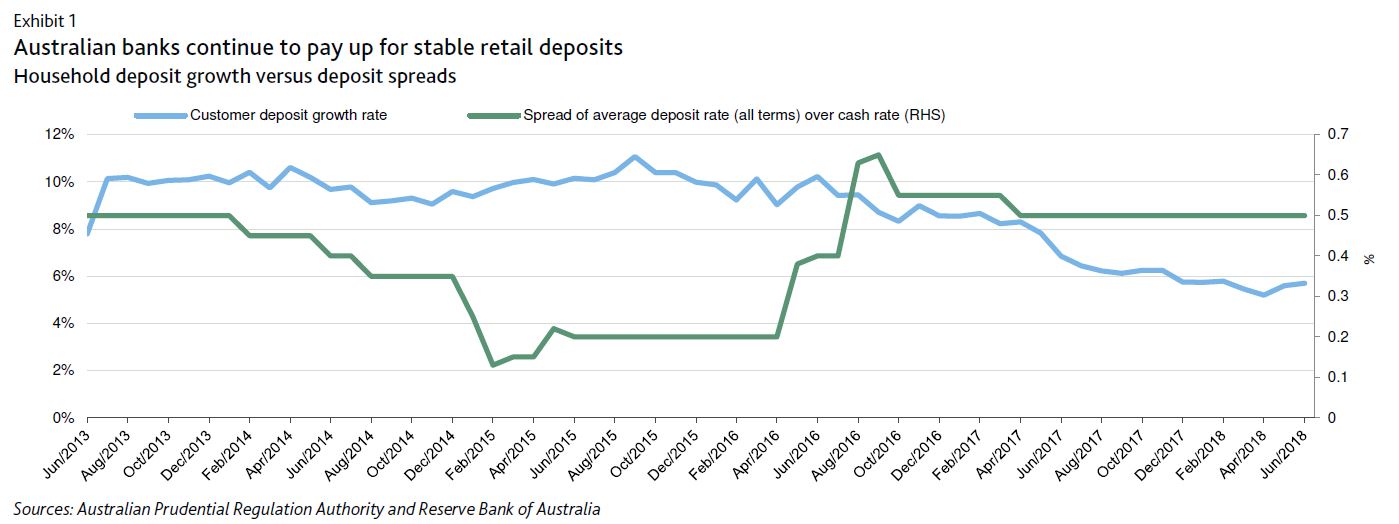

Bank Australia is a mutually owned bank that is primarily deposit-funded and must compete with larger commercial banks at a time when deposit growth has been slowing, but new liquidity regulations have incentivised banks to gather stable customer deposits. This has caused average deposit spreads to remain high.

The ability to diversify funding to include wholesale sources is therefore attractive. However, Bank Australia is a small mutually owned bank with a market share of 0.2%. Its limited scale means that, inevitably, investors will not have the same familiarity with its credit profile as Australia’s major banks, such as the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. This makes it more challenging and costly for Bank Australia to raise long-term funding in the senior unsecured market.

However, increasing investor interest in environmental and socially responsible investing has provided an opportunity for issuers like Bank Australia to tap longer-tenor wholesale funding in meaningful amounts.

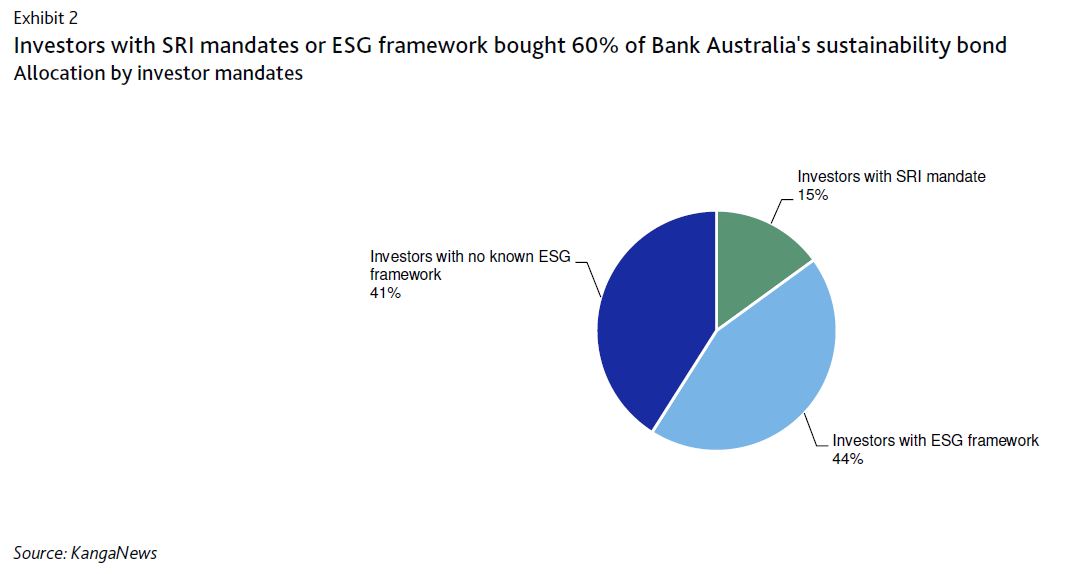

A total of 60% of Bank Austalia’s AUD125 million sustainability bond issuance was allocated to investors with socially responsible investing (SRI) mandates or an ESG framework (Exhibit 2). The scale of investor demand also allowed the bank to increase its final issuance by 25% over the initial offer and to improve its pricing.

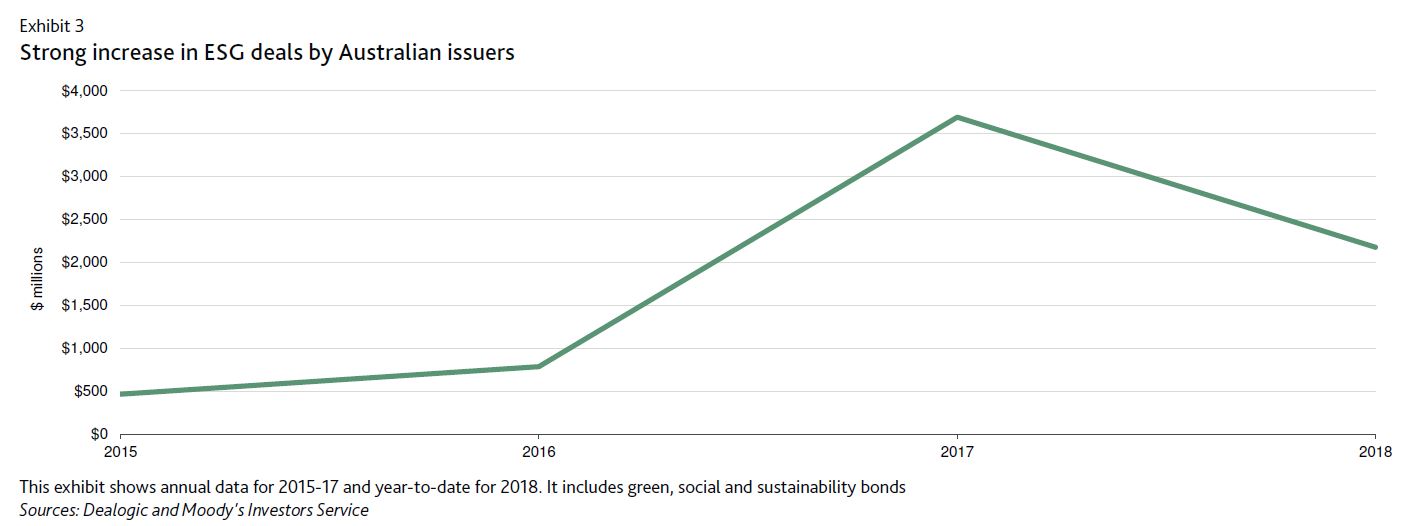

Other Australian issuers have also gained traction with bonds providing environmental and social benefits. Teachers Mutual Bank Limited, another small mutual bank, sold an ethical bond in June 2018. Demand has driven Australia’s issuance of green, social and sustainability bonds in the past four years at competitive spreads compared with regular issuance.

Following its sustainability bond issue, Bank Australia’s wholesale funding will increase to 12% from 10% of total funding, on a pro forma basis. Importantly, the sustainability bond, which has a tenor of three years, will lengthen the bank’s overall funding maturity profile.

Bank Australia will likely be able to issue further sustainability bonds in future, because of its involvement in social and environmental projects. For example, it makes loans for affordable housing, community housing, and disability housing.

We expect issuers’ increasing awareness of the benefits of issuing green, social and sustainability bonds to spur additional supply. There is some risk that issuance by larger banks may crowd out some small issuers like Bank Australia. However, any increase in issuance will build on a low base since these notes comprise only 2% of total issuance so far in 2018, according to financial market data collector Dealogic. Investor demand is also growing and is likely to absorb more supply.