When it comes to discussions about Chinese real estate investors, we tend to focus on the idea that they are buying up property in places like Australia, pushing up prices – even if that is somewhat questionable. But it also ignores the other side of the equation. The number of properties built by Chinese developers outside of China has grown significantly, even as residential construction within China slows.

The expansion of Chinese residential development outside China has impacts on a number of levels, from property prices through to regional diplomacy.

The shift to Asia

Country Garden, a property development company based in Guangdong, China, is constructing apartment buildings that would add more than half-a-million homes and house 700,000 people in Johor Bahru, in southern Malaysia. This project goes far beyond constructing apartment buildings, however. It is part of an even bigger project named “Forest City” that Country Garden plans to build on four artificial islands.

The idea is that Forest City will be equipped with schools, shopping malls, parks, hotels, office buildings and banks. All ensconced in rich greenery, clean water and a quiet transportation system.

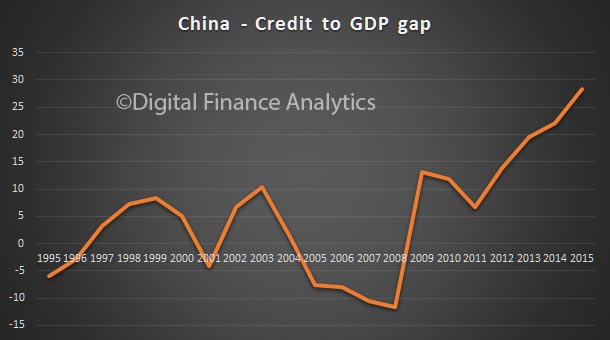

This grand project is just one example of the recent surge of overseas investment by Chinese property developers. Total investment in the Chinese real estate sector was growing at a rate above 10% until 2014, then dropped to less than 1% in 2015. This indicates a significant shift in Chinese real estate investment.

All the while, Chinese investment in the real estate sector overseas has picked up strongly. It has grown from $US0.6 billion in 2009 to US$30 billion in 2015. Several Chinese property developers have identified overseas investment as their main business growth strategy.

Two reasons for the pivot

Chinese investors have begun looking offshore for a couple of reasons.

Chinese buyer demand for overseas properties is growing. Since China reformed its economy and started growing at a fantastic rate, households have accumulated significant wealth. They now want to diversify their investment portfolios, and so are seeking property elsewhere.

Volatility in domestic housing prices has intensified this trend, despite various government policies aimed at smoothing out price fluctuations. An oversupply of properties in third and fourth-tier cities such as Ordos and Qinhuangdao created “ghost towns” where property isn’t desirable. In first and second-tier cities, however, prices have skyrocketed. House price-to-income ratios of these cities are ranked highest in the world, making it difficult to invest in properties in China.

In recent years there has been a huge expansion of production capacity. In 2015, China produced 51.3% of the cement and 49.5% of the crude steel in the world. As production capacity grows beyond the demand from the domestic market and runs into overcapacity, it is natural that firms will seek returns overseas.

The impact of it all

Taking Country Garden as an example, it is worth noting that the developer is not just building residential property, but designing and constructing the entire infrastructure for a city. Transport, greenery, water and noise control are all being put in place. These are beyond the scope of a conventional property developer.

Therefore, one potential positive impact of this project is to help boost the quality of infrastructure in Johor Bahru and so nurture more business activities in the future. The economic and geographic relationships between Johor Bahru and neighbouring Singapore may develop into one similar to that between Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

It is, however, critical that the local government monitors and enforces strict environmental protection and regulation to ensure the project won’t damage the natural environment or disrupt the local market.

The huge influx of newly built apartments has resulted in the value of residential sales dropping by almost one-third in in Johor Bahru last year. Whether this is a short-run phenomenon and housing prices will rally in the long run depends on whether more business activities and job opportunities can attract population inflow to the city and hence create higher demand for housing. In the short run, the fall in housing prices may lower the cost of living and attract firms and workers into the city.

For the Chinese government, it will be important to nurture more talent with legal and financial expertise to help Chinese property developers go out and invest overseas. This expansion by developers is just one, early facet of China’s new diplomatic efforts to develop infrastructure overseas.

Author: Lecturer in Economics, Curtin University