We just learned America’s rental affordability crisis is as bad as it’s ever been. Unfortunately, it’s about to get a whole lot worse.

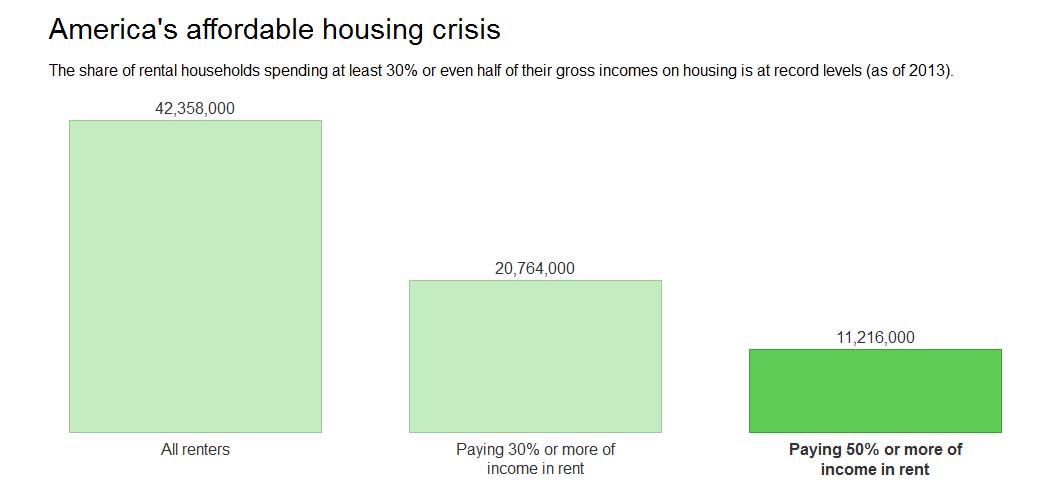

The American Community Survey for 2014, released a few weeks ago, found that the number of renters paying 30% or more of their income on housing – the standard benchmark for what’s considered affordable – reached a new record high of 20.7 million households, up nearly a half-million from the year before. Despite the improving economy, the increase was nearly five times bigger than last year’s gain.

That means about half of all renters live in housing considered unaffordable. And the latest increase comes on top of substantial growth since 2000 that has seen this number climb by roughly six million households over the period, an increase of about 41%.

Worse still are the more than 11 million households with severe cost burdens, paying more than half their income for housing, up from seven million at the start of the century.

Having so many families and individuals struggling to pay their monthly rent is a clear cause for concern. Renters in this situation are forced to make difficult trade-offs to make ends meet, including opting for housing in distressed neighborhoods or in poor condition. In fact, in an analysis of consumer expenditure data we undertook at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, we found that renters in this situation largely accommodate their high housing costs by spending substantially less on such basic needs as food and health care.

This growing problem needs to be addressed because having a stable, decent home has been found to produce a wide variety of benefits, from better health outcomes to improved school performance among children. There is also growing evidence that providing permanent affordable housing for homeless individuals and families is much more cost effective than paying for temporary housing.

With the housing crash receding from the headlines and prices on the rise again, it is all too easy to believe that as the economy heals, the housing affordability crisis will naturally ebb without the need for greater efforts by our public leaders.

Unfortunately, this is wishful thinking.

Prospects for improvement

The rising tide of cost-burdened renters has its roots both in the real (inflation-adjusted) growth in the cost of rental housing and in falling renter incomes.

Since 2001, the median monthly rental price in the US has climbed significantly faster than inflation, while the typical renter’s pretax income has fallen by 11%. These trends were evident even before the recession and housing bust, but have certainly been exacerbated by the economic travails since.

Now that the economy is nearing full employment and holding out the prospect of a rebound in incomes and construction of new apartments is reaching levels not seen since the 1980s, there would seem to be some hope that the extent of rental cost burdens would start to abate. But at the same time, there are also demographic forces at work that are likely to make matters worse.

The two fastest-growing segments of the population in coming years will be those over age 65 and Hispanics, both of which are more likely to experience cost burdens.

In collaboration with researchers at the affordable housing nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners, the Joint Center for Housing Studies set out to simulate future trends for cost-burdened renters based on our household projections for the next decade under different scenarios in which rents continue to outpace incomes, or, alternatively, where we see a turnaround in current conditions and incomes grow faster than rents.

As we document in our recent report, we found that demographic forces alone will push up the number of renters with severe rent burdens by 11% to more than 13 million by 2025, with a large share of the growth among the elderly and Latinos. That’s assuming incomes and rents both grow in line with overall inflation.

If we do get lucky enough to see gains in income outpace the rise in rents by 1% annually over the next decade, we would see a modest decline of some 200,000 renters with severe burdens. That’s some improvement but not nearly enough to appreciably change the current challenge. And this modest net improvement would mask a still-significant growth in rent burdens among Hispanics of 12%.

But alternatively, if rents continue to grow faster than incomes at a pace similar to what we see today, we could see the number of renters spending more than half their income on housing reach 14.8 million, an increase of 25% over today’s record levels. That would mean 31% of US renters – and most likely at least a few of your family and friends – would be desperately struggling to get by.

What can we do about it?

So what do we need to do to address this situation?

Since falling incomes are a key part of the problem, efforts to raise take-home pay will have to be part of the solution. Increases in the minimum wages will help to some extent. Improvements in education and job training that prepare people for decent paying jobs are also needed.

On the housing front, there is also a strong case for an expansion of assistance for the nation’s lowest-income households. About 28% of renters earn less than US$20,000 a year. At that income, monthly housing costs have to be $500 or less to be affordable.

The private market simply can’t supply housing at such low rents. Public assistance is needed to close the gap. However, at present only about one out of four households who would qualify for this federal housing assistance based on their income is able to secure one of these units. Unlike other programs in the social safety net, housing assistance is not an entitlement. And we simply don’t come anywhere close to fully funding housing assistance to help all those eligible.

The vast majority of those who are left out face so-called worst-case housing needs, paying more than half their income for housing or living in severely inadequate housing.

Solving the housing problem

There are two main ways in which we have extended housing assistance in recent decades: 1) by providing housing choice vouchers that subsidize monthly costs for homes the tenant finds in the private market or 2) by subsidizing the cost of new housing or the rehabilitation of existing housing with support of the Low Income Housing Tax Credit.

Both programs have their place. In markets where modestly priced housing in a range of neighborhoods is not in short supply, vouchers make sense as a means of taking advantage of housing that already exists. Vouchers also have the potential for giving greater choice about where residents want to live in a metro area.

The housing credit program also plays an important role in helping to preserve existing subsidized housing that needs new investment, in helping to turn around neighborhoods where new housing can have a positive impact and in adding affordable housing in neighborhoods where it would not otherwise be provided.

Still, both programs could benefit from reforms to ensure that funds are used efficiently and that the housing opportunities provided are not concentrated in distressed neighborhoods.

For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development recently started a pilot program that factors the variability of market rental prices across neighborhoods into the maximum rent its vouchers cover. Currently, the limit it is set at is the same for an entire metropolitan area. The new approach would allow that limit to vary across neighborhoods, giving beneficiaries more choice in where to live and also keep HUD from overpaying in distressed areas.

There are also proposals for reforming the housing tax credit program to allow it to serve a broader range of income levels and make it easier for people to get aid in high-cost markets like New York, San Francisco and Boston, where rental burdens are increasingly a problem among moderate-income households and not just the poor.

The grass roots

Beyond these federal efforts, state and local governments also have an important role to play in fostering a greater supply of affordable housing.

In addition to providing public funds for this purpose, these levels of government set land use regulations and policies that have the potential to spur affordable housing production. But all too often, they deter affordable housing production through complex and costly approval processes as well as limits on the types of housing that can be built.

With both demographic and economic trends likely to keep the number of cost-burdened renters at record levels for years to come, the issue is not going to go away. But we still lack the political urgency to take the steps needed to do something about the problem; housing affordability hasn’t even come up in any of the presidential debates.

It may be because it has historically been borne by the nation’s most disadvantaged families and individuals. But with the number of cost-burdened renters reaching highs each year, the challenge of paying the rent each month is becoming a significant concern for a broader swath of the country with each passing year.

It’s time our political leaders take notice and take action.

, Managing Director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, Andrew Jakabovics, senior director for policy development and research at affordable-housing nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners.