Consumers have more protection when buying a new fridge, than when buying a new property – according to an article in the The Conversation.

Regulation of the Australian building industry is broken, according to the Shergold-Weir report to the Building Ministers’ Forum (BMF).

[…] we have concluded that [the] nature and extent [of problems] are significant and concerning. The problems have led to diminishing public confidence that the building and construction industry can deliver compliant, safe buildings which will perform to the expected standards over the long term.

You can say that again.

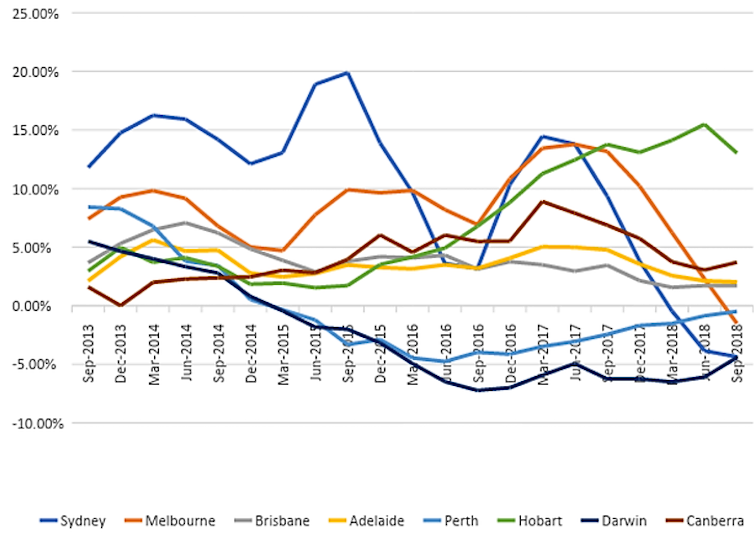

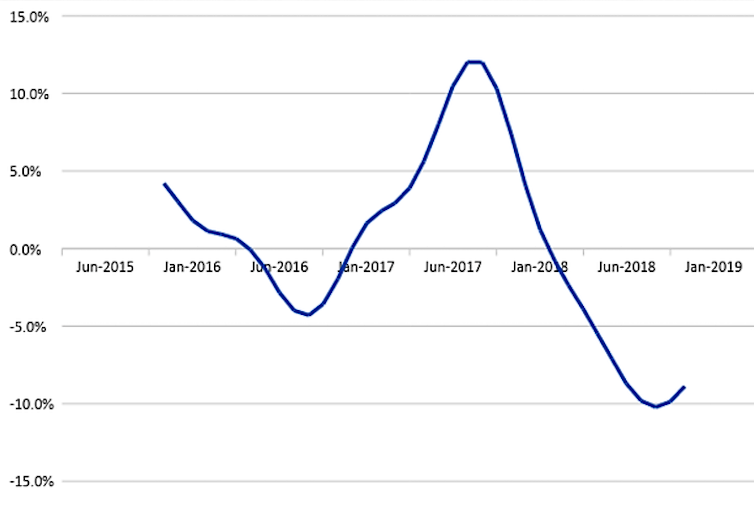

Just one of the issues identified in the report, combustible cladding, could affect over 1,000 buildings across Australia. An unknown proportion of these are tall (four storey and above) residential strata buildings. Fears of rectification costs are starting to have severe impacts on the apartment market.

The cost of replacing combustible panels at the Lacrosse Apartments in Melbourne, which caught fire in 2014, will be at least A$5.7 million, plus A$6 million or so in consequential damages. The total cost of replacing combustible panels across Australia is unknown at this point, but is likely to run to billions of dollars.

The Shergold-Weir report identifies a catalogue of other problems, including water leaks, structurally unsound roof construction and poorly constructed fire-resisting elements. Faults appear to be widespread.

A 2012 study by UNSW City Futures surveyed 1,020 strata owners across New South Wales and found 72% of respondents (85% in buildings built since 2000) knew of at least one significant defect in their complex. Fixing these problems will cost billions more.

Regulatory failures are not only “diminishing public confidence”, they have a direct impact on the hip pockets of many Australians who own a residential apartment. In short, building defects resulting from lax regulation are a multi-billion dollar disaster.

How could authorities let this happen?

A web of regulations and standards enacted by governments cover construction in Australia, but this regulation is centred on the National Construction Code (NCC). The Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB), a body controlled by the Building Ministers’ Forum, manages the NCC. The ABCB board comprises appointed representatives from the Commonwealth plus all the states and territories and a few industry groups.

It is such a complicated system that it is hard to identify any government, organisation or person that is directly responsible for its performance.

The NCC is supposed to create “benefits to society that outweigh costs” but it appears the ABCB may have been more focused on the need to “consider the competitive effects of regulation” and “not be unnecessarily restrictive”. (Introduction to the NCC Volume 1; ABCB)

The BMF’s February 8 communique, issued after the fire in the Neo200 building in Melbourne, is straight out of the Yes Minister playbook:

Ministers agreed in principle to a national ban on the unsafe use of combustible ACPs (aluminium composite panels) in new construction, subject to a cost/benefit analysis being undertaken on the proposed ban, including impacts on the supply chain, potential impacts on the building industry, any unintended consequences, and a proposed timeline for implementation. Ministers will further consider this at their next meeting [in May this year].

This suggests the ministers are more concerned about possible impacts on the panel suppliers and the building industry than the consumer. The earliest a ban can take effect is in May. In the meantime, anecdotal evidence suggests buildings are still being clad in combustible ACP.

Thanks to the journalist Michael Bleby, we know governments and the ABCB failed to act in 2010 when presented with evidence that combustible ACP was not only a danger, but was also being widely used on tall residential buildings.

Bleby quoted ABCB general manager Neil Savery as saying neither his organisation, nor any of the states, was aware that builders were using the product incorrectly.

We also know that panel manufacturers, including the Australian supplier of Alucobond, actively lobbied building ministers. At the July 2011 BMF meeting, the ACT representative effectively vetoed an ABCB proposal to issue an advisory note on the use of combustible ACP.

We are entitled to ask why the ABCB and its staff, or the downstream regulators and their staff, did not know about serious fire problems with ACP that the technical press identified as long ago as 2000. The answer will be of particular interest to residents of tall apartment buildings clad in these panels, all of whom are now living with an active threat to their safety.

Consumers are owed better protection

While both Labor and Coalition governments have worked to improve consumer protection for people buying consumer goods, their record on housing, particularly apartments, is awful. While a consumer can be reasonably sure of getting restitution if they buy a faulty fridge, no such certainty exists if they buy a faulty house or apartment.

At the moment, the NCC does not have any focus on providing protection for buyers of houses or apartments. There are few requirements for the durability of components and astonishingly weak requirements for waterproofing. Under the NCC and its attached Australian Standards, particularly AS 4654.1 and 2-2012, a waterproof membrane could last, in practice, five minutes or 50 years.

Given the magnitude of the economic loss, it would be appropriate for the BMF and ABCB board to publicly admit they have failed. Since their appointments in November 2017 and January 2013 respectively, neither ABCB chair John Fahey nor Savery as general manager has remedied the situation. The Shergold-Weir report has not been implemented and the combustible cladding issues remain unresolved. It would be reasonable for Fahey to step down and for Savery to consider his future.

The next federal government should consider what further action should be taken, particularly in relation to individuals on the BMF and within the ABCB involved in the 2010-2011 decision not to issue the proposed advisory note on the use of ACP. Since the ABCB does not publish minutes and none of its deliberations are in the public domain no one knows what actually happened or who did what.

The new board should consider moving residential apartment buildings (Class 2 buildings in the NCC classification) from Volume 2 of the NCC to Volume 1, which controls detached and semi-detached housing. Volume 1 should then have as its overriding objective the protection of consumers.

The downstream regulators should focus on requiring builders to deliver residential buildings with no serious faults and providing simple mechanisms for redress if they don’t.

Surely this is not too much to ask.

Author: Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Lecturer in Architecture, UNSW