The way “gig workers” are paid and protected might be about to change, as a result of legal proceedings brought by the Fair Work Ombudsman. The Ombudsman alleges that food-delivery platform Foodora underpaid three workers by A$1620.74, plus superannuation, in a four-week period.

The Ombudsman argues that while Foodora engaged these workers as independent contractors, they were in reality employees. If the action succeeds, it could be positive for the underpaid workers, but it could also drive down working conditions.

The food-delivery platforms have stated they would be willing to give their workers more benefits, such as training. But not at the cost of workers being classified as employees. If the Ombudsman’s case succeeds, it could cause gig platforms to offer fewer protections in order to ensure workers are classified as contractors.

This could not only disrupt the food-delivery sector, but have a broader impact on the gig economy, restaurants, customers and workers.

Employees or contractors?

The difference between an employer and a contractor is significant. They fall under different laws, receive different protections and have different obligations.

If a contractor performs poor work they are legally liable for that. But an employer is responsible for the poor work of an employee.

In many cases this distinction is clear-cut. However, in the gig economy these workers operate in a grey area, one the Fair Work Ombudsman seeks to test.

Whether workers can be classified as employees or contractors depends on a variety of factors, including the nature of the work. If workers are deemed employees then they receive a greater number of protections, including minimum wage rates.

In the Australian platform-based economy (including ride sharing and food delivery), the Fair Work Commission has determined workers are independent contractors in two recent cases.

In one case, Commissioner Nick Wilson stated that “[the driver] did not bring anything especially entrepreneurial to the arrangement” but also that “it is evident that the weight of those indicators leads to the finding that [the driver] was not engaged as an employee, but instead as an independent contractor”.

The Fair Work Ombudsman’s decision to intervene in the food-delivery sector might be a response to poor working conditions for gig workers. But the decision to go after Foodora specifically could dissuade rather than encourage other platforms to improve working conditions.

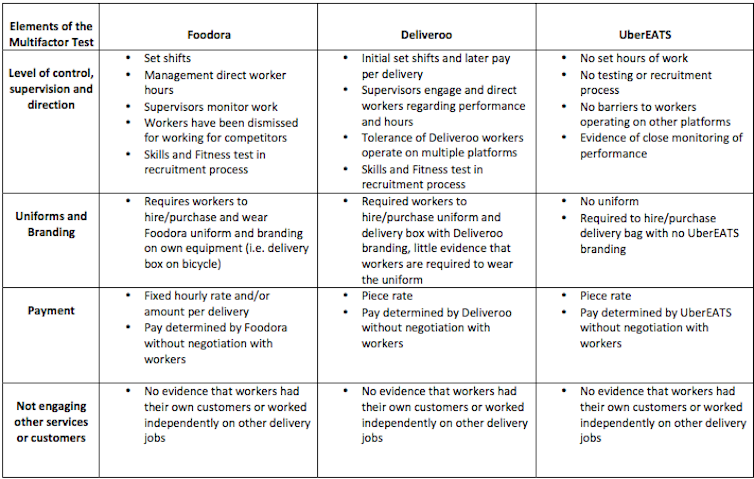

As shown in the table below, the three major food-delivery platforms have varying approaches to engaging workers. For instance, Foodora, in the period under investigation, would engage workers for set periods of time, rather than per delivery. Deliveroo and Foodora also provided uniforms for workers, while UberEATS did not.

Authors’ original work based on Fair Work Ombudsman, The Australian Financial Review, The Guardian Australia, original research.

The fact that the case was brought against Foodora suggests that the company has the most direct relationship with workers, and thus its workers are most likely to be classified as employees.

Our research shows, however, that these work practices are evolving all the time.

In submissions to the ongoing Senate Select Committee on the Future of Work and Workers, both Deliveroo and UberEATS claimed they would like to provide additional benefits to workers but doing so in the existing regulatory environment might compromise their business models.

For instance, Deliveroo argued that it “… wishes to be able to provide additional benefits to [workers] without the risk of those benefits changing the relationship from one of self-employed riders to riders employed by Deliveroo”.

UberEATS similarly argued that “current employment classifications create significant disincentives: they can mean that offering training to these [workers] can compromise the self-employed status of the individual. We believe that companies should be incentivised, not penalised, for helping independent workers”.

This is why the Fair Work Ombudsman’s decision to target Foodora may be counterproductive. It sends the signal that the better you treat your workers, the more likely they are to be classified as employees, the more expensive your labour costs will be and the more inflexible your operation will become.

The Foodora case is interesting as it applies existing employment rules to “gigified” work. Currently, some gig workers earn significantly less than the minimum wage. They also miss out on other protections of employment.

However, unlike high-profile franchising cases such as the underpayment of 7/11 workers, their current classification as contractors means this practice is within the law.

If the Fair Work Ombudsman is successful and these workers are reclassified as employees, it might provide a disincentive for other platforms to protect workers. The law itself might need to change.

With this in mind, we all need to pay attention to the recommendations of the Senate Select Committee on the Future of Work, due on June 21.

Authors: Tom Barratt, Lecturer, School of Business and Law, Edith Cowan University; Alex Veen, Scholarly Teaching Fellow in Work and Organisational Studies, University of Sydney; Caleb Goods, Lecturer – Management and Organisations, UWA Business School, University of Western Australia